Saving Deccan Chronicle

Much like the Deccan Chargers team they owned, the Reddy brothers, the founders of the Deccan Chronicle group, seemed virtually unstoppable. Till their luck began to run out

It started sometime around 2005, the borrowing. The amounts were small to begin with. A Rs 20 crore here from ICICI Bank, Rs 25 crore there from Canara Bank.

Like a drug coursing through veins, hiding sorrows and boosting happiness, so too did the money, smoothening cash flows, masking operational inefficiencies and funding loss-making ventures.

At annual interest rates ranging from 6 to 10 percent, the drug was cheap, too. And before it knew it, Deccan Chronicle Holdings, one of South India’s largest newspaper publishers, was hooked.

Soon even those sums started to appear trifling, so they went up. About Rs 100 crore from IL&FS, Rs 400 crore from Canara Bank and Rs 550 crore from Andhra Bank. They came with various names—working capital advances, credit facilities, term loans, non-convertible debentures, foreign currency convertible bonds. As the amounts went up, so did the interest rates, which now ranged between 13 and 16 percent.

To keep the cash flowing, practically everything that could be mortgaged was mortgaged.

The parcels of land scattered across states, the offices, the newsprint inside warehouses, the receivables from vendors and advertisers, the machinery and even the printing presses.

It was the printing presses, though, that defined the three-decade-long legacy of Tikkavarapu Venkattram Reddy, the company’s 53-year-old flamboyant and impulsive chairman.

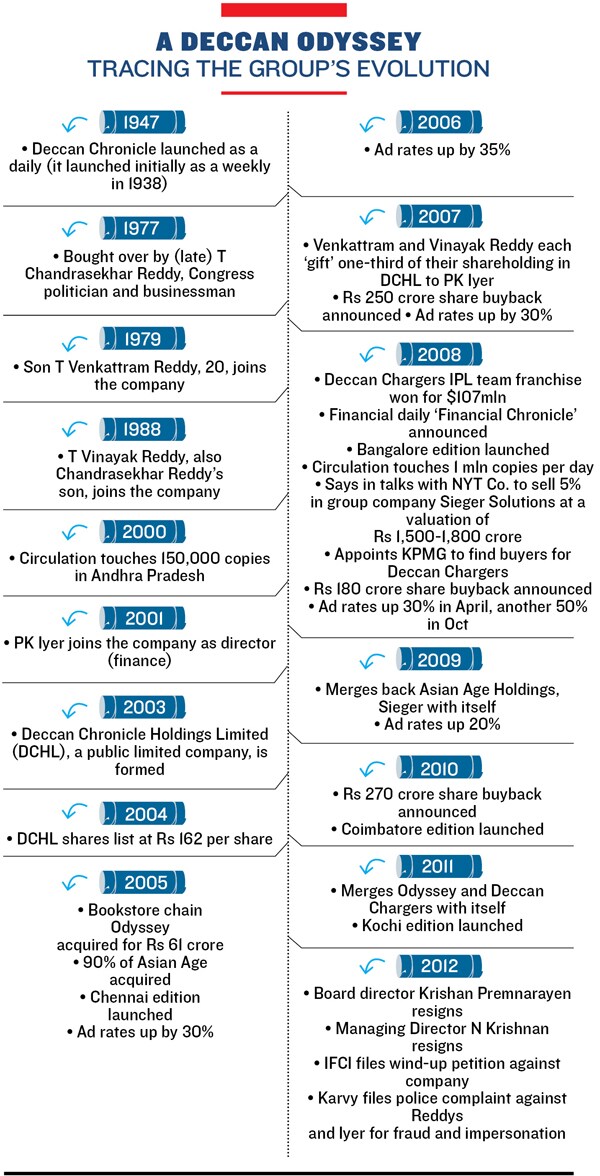

He began work at the newspaper as a 20 year old in 1979, just two years after his late father T Chandrasekhar Reddy bought it from its original founders who had been printing it for nearly four decades in Hyderabad.

From dumping letterpress printing in favour of the sharper and cleaner offset printing in 1980 to introducing high-quality colour printing using heat-offset in 1998 to buying highly automated multimillion dollar Goss presses in more recent years, Reddy believed modern printing presses were key to success in the newspaper market.

Yet today his beloved presses, from Hyderabad and Visakhapatnam in Andhra Pradesh to Coimbatore and Chennai in Tamil Nadu, lie mortgaged with banks. Meanwhile Reddy and his younger brother and equal partner in the business, T Vinayak Ravi Reddy, rush from one lender to another, borrowing from one, paying back the next.

All the shares representing the Reddys’ ownership of Deccan Chronicle are mortgaged with lenders, maybe even twice over in some cases as alleged by a complaint of forgery by the Karvy Group. One of its lenders, the Industrial Finance Corporation of India (IFCI), has filed for the company to be wound up in order to receive an overdue loan amount of around Rs 28 crore. Newspaper reports estimate the size of the company’s overall debt at around Rs 1,500 crore.

The Reddys are staking every asset—personal or otherwise—to stave off what many might consider an inevitability: A total collapse of their media empire and sale to a rival.

A Business Model in Peril

In hindsight, while many are saying Deccan Chronicle had it coming for years, fact is, till as recently as 2010 the company was considered a textbook example of how to run a modern newspaper business.

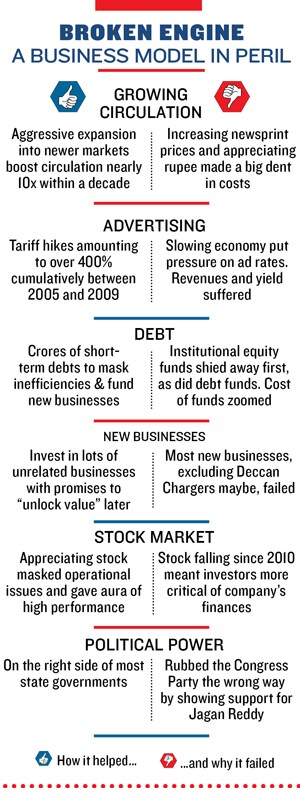

Within a decade, it went from being primarily a one-city newspaper in 2000 with a circulation of roughly 150,000 copies and annual revenues of Rs 55 crore to nearly 10 times the circulation and roughly Rs 1,000 crore in revenue by 2010.

For much of that period, it threw out spectacular numbers—EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation) profit margins upwards of 50 percent apparently successful edition launches in new markets like Chennai and Bangalore advertising rate hikes ranging from 30-35 percent every year, and substantial net cash flows (Rs 215 crore in 2009 and Rs 399 crore in 2010).

Along the way, it also bought or created numerous other businesses of which the two largest ones were Odyssey, a retail bookstore chain it acquired in 2005, and Deccan Chargers, an IPL cricket franchise it bid for and won in 2008.

Its share price kept appreciating, shooting from Rs 162 upon launch in December 2004 to Rs 900 in just over two years before going for a five-for-one split.

Yet, behind the headlines and under the hood, its core business was slowly losing its edge over the last three-four years.

Ironically, one of the reasons for that might have been Venkattram Reddy’s unshaken faith in his beloved printing presses.

The presses—modern machines churning out tens of thousands of copies every hour with minimal human intervention—were the linchpin of Deccan’s growth strategy. Printing newspapers faster and more efficiently than its competitors allowed Deccan to claim spectacular increases in ‘circulation’ each year, in both existing and new markets.

In Chennai and Bangalore, it claimed an Audit Bureau of Circulation (ABC) certified circulation of 300,000 and 243,000 copies, both within a year of launch. The Hindu in Chennai even went to court, unsuccessfully, to prevent Deccan from crowing over its ABC figures.

The higher circulation was then used as a justification to increase advertising tariffs. Tariffs were increased every year from 2005 to 2009, including twice in 2008, adding up to a cumulative increase of over 400 percent.

Outside of its home market of Hyderabad and Andhra Pradesh (where it and other incumbents were said to have formed a loose alliance to prevent price competition when The Times of India entered the market), Deccan resorted to discounting its cover price to win over subscribers and market share. This has led to a continuous drop in its circulation revenues over time, from 18.5 percent of total revenues in 2003 to just 6.5 percent in 2011.

Of course, the other side of this trend was that Deccan became dangerously dependent on advertising over time, with nearly 90 percent of its revenues in 2011 coming in through that route.

Most large newspaper groups, including past masters of price competition like The Times of India and Dainik Bhaskar, had over the years started reducing their dependence on price discounts. Maintaining healthy circulation revenues was also considered a hedge against the notorious cyclical nature of advertising.

For instance, Jagran Prakashan and DB Corp, two of the biggest regional newspaper groups that are listed, reported circulation revenues of around 19 percent and 16 percent, respectively, in their latest quarterly earnings.

The Perfect Storm

The year 2010 brought with it the perfect storm for Deccan Chronicle’s business.

First, the cost of printing a newspaper shot up due to increasing newsprint prices and a depreciating rupee. According to Fitch, a rating agency, the price of imported newsprint rose between 30-40 percent from early 2010, including an increase of 13.4 percent in 2011 alone. Given that just newsprint accounted for 43 percent of Deccan Chronicle’s expenses in 2010, that bled a lot of money.

Second, the prolonged economic slowdown and uncertainty since 2010 caused most advertisers to tighten their purse strings.

Notwithstanding Deccan Chronicle’s published ad rates, most large and medium advertisers who worked through media agencies paid significantly lesser amounts, says a senior media planner in Bangalore.

According to data provided by him, the discounts were least in Hyderabad and the rest of Andhra Pradesh where Deccan was the undisputed leader and ranged from 14 to 43 percent. But in newer markets like Chennai and Bangalore where Deccan’s circulation-driven strategy seemed to splutter away after the initial bombast, the discounts ranged from 53 to 74 percent.

Even in its home markets, the Telangana agitation that gathered momentum following the death of the Andhra Pradesh chief minister, YS Rajasekhara Reddy, in September 2009 scuppered its ad market over most of 2010 and 2011 causing declines in revenue and profit margin.

Its stock price that had risen to Rs 173 in March 2010 from just Rs 32 a year ago would then reverse the trend permanently. Over 2010 and 2011 it lost nearly 80 percent of its value. As on August 23 this year, it languishes at Rs 11.

Squeezed on all sides from the cost, revenue and stock market valuation aspects, something was bound to give.

A Game of Leveraged Dominoes

In the last week of July, IFCI filed a petition in the Andhra Pradesh High Court at Hyderabad asking for Deccan Chronicle to be wound up as it did not have any money left to pay off its loans.

Rating agency CARE promptly revised the company’s debt downward from the earlier ‘AA’ for its long-term debts (which indicate a high degree of safety regarding timely servicing of financial obligations) and ‘A1+’ for its short-term debt.

But by then the damage had already been done.

Pramerica, a mutual fund that had been investing into Deccan Chronicle’s corporate debt for the last two years, had to write off its entire Rs 50 crore loan as a loss on its balance sheet.

IDFC’s treasury department, incidentally a banker to Deccan Chronicle’s debt, had to write off Rs 145 crore on its balance sheet. A detailed questionnaire to IDFC for this story remained unanswered. A detailed questionnaire to Deccan, too, remained unanswered, nor did Venkattram Reddy respond to SMS.

Most of the losses have hit debt funds even as their equity counterparts escaped unscathed.

Yet strangely, debt funds seem loathe to blame CARE, its credit rating agency, saying that the problems on Deccan Chronicle’s balance sheet weren’t evident.

That is both rich and generous to a fault, considering that Deccan Chronicle has, even five months on, yet to publish its audited financial results for the year ending March 2012. Last year, it spent 19 percent of its total debt just on interest payments, up from 13 percent the year before.

These are worrying numbers that ought to scare off any sober investor, yet CARE rated Deccan Chronicle’s debt as safe, going by guarantees provided by Deccan Chronicle’s bankers. And debt investors happily went by that rating.

It was only after IFCI filed the suit against Deccan Chronicle that CARE hastily changed the company’s debt rating.

“A thorough and diligent analyses of key ratios, including working capital indicators, debtor build up is crucial as this can provide important pointers on strained liquidity,” says Ramraj Pai, president, CRISIL Ratings, a rival rating agency.

Equity funds in contrast seemed much more informed and diligent.

Senior fund managers say Deccan Chronicle’s balance sheet was somewhat odd even as far back as 2006. It had a cash balance of Rs 205 crore, and debt worth Rs 296 crore. That the company refused to retire the debt using its cash was seen as a worrying signal.

As early as October 2007, a report from ICICI Securities (I-SEC) recommended a “Sell” on Deccan Chronicle arguing that the company’s 261 days worth of receivables in 2007, compared to 60-90 days for its peers, pointed to a curious case of cashless growth.

Almost all the debt investors, who spoke off record, were not aware of the I-SEC report even as all their institutional equity peers knew about it.

According to Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE) filings, ICICI Mutual Fund was one of the biggest investors in Deccan Chronicle for a long time. Yet, by the end of 2008, it had sold off all of its 7 percent holding in the company, as it is believed that the fund spotted some cracks in the company’s balance sheet in 2007. More recently, other institutional investors too pared down their holdings in Deccan Chronicle from 20 percent in June 2011 to just 8 percent currently.

When quizzed by analysts, the company had a standard response. PK Iyer, its CFO and later promoter, would talk his way out of these questions by saying his business required a lot of working capital and that cash was king on any balance sheet.

The debt investors were convinced by his argument. Emboldened, Deccan Chronicle kept borrowing short-term debt for working capital purposes year after year. The Iyer of the Storm

The Iyer of the Storm

On July 25, 2007, both Venkattram and Vinayak Reddy did something unprecedented and inexplicable, befuddling even diehard analysts of Indian businesses: Each brother sliced out a third of the shares he held in the company and ‘gifted’ it to PK Iyer, the head of their finance function.

The shares were worth Rs 1,170 crore and overnight turned Iyer into an equal with Venkattram and Vinayak, with each owning 20.36 percent of the company.

It was a stunning culmination for Iyer who had joined Deccan Chronicle just six years earlier in 2001. By 2003, he was promoted to an executive director in the company and was highlighted in the company’s IPO prospectus as a key management team member right after Venkattram and Vinayak.

No one was quite sure of his exact credentials. For instance, his educational background alternated between a bachelor’s degree in science in some annual reports to a bachelor’s degree in economics and a master’s degree in business management in others.

According to a senior fund manager based in Mumbai who had interacted with him numerous times, Iyer was fond of projecting a larger-than-life persona. “In another life, I would have played tennis for India on its Davis Cup team,” he would brag, claiming to have played extensively with the Amritraj brothers.

“When I asked him why his company’s cash flows were so poor, he had no answer. ‘Forget that, look at our EPS [earnings per share],’ he said,” recalls a fund manager who interacted with him personally. “He seemed clueless about finance and accounting.”

And yet, Iyer was widely considered by most people as the ‘brains’ behind most of the group’s financial successes, including its IPO.

After the Reddy brothers ‘gifted’ him one-fifth of their company, Iyer became maniacally obsessed with Deccan Chronicle’s stock price. For instance, he is reliably learnt to have convinced one of India’s leading financial groups to withdraw a negative research report on his company in 2007 by threatening to cut them off from banking transactions.

In just the six months from July 2007, when he was ‘gifted’ 20 percent of the company, to January 2008, Iyer crafted a dizzying number of strategies—a Rs 250 crore share buyback plan when its total debt just three months back stood at Rs 528 crore a decision to solicit private investments in the group’s wholly owned ad-sales arm Sieger Solutions at a valuation of between Rs 1,500-1,800 crore a joint venture with WPP-owned media agency Group M to do sports and events marketing a $107 million winning bid for the ‘Deccan Chargers’ IPL cricket team and the decision to launch Financial Chronicle, the group’s financial daily.

For a company so heavily indebted and forced to raise loans worth many hundreds of crores to provide it with working capital for operations, under Iyer, Deccan Chronicle surprisingly found a lot of money to buy back its own shares. Following the Rs 250 crore offer in 2007, there was a Rs 180 crore offer the very next year and a Rs 270 crore offer in 2010. The money came from the company’s free reserves and surplus, which kept increasing year after year alongside its debt.  The Pendulum Swings Back

The Pendulum Swings Back

“The net worth of Deccan Chronicle Holdings far exceeds its current outstanding. The loan outstanding and the overdue sums relate to payments that were due only in the last couple of months,” said Venkattram Reddy in a statement on August 2. “Deccan Chronicle’s value as a 75-year-old leading newspaper, the value of its fixed assets comprising land and buildings as well as plant and machinery at multiple locations, and the value of the Deccan Chargers IPL team far exceed the company’s debt.”

He and his brother are directly supervising the financial cleanup and rescue, leaving no asset un-mortgaged and no lenders uncalled. All efforts are being made to ensure that staffers are paid salaries on time, say insiders.

Meanwhile, Venkattram may well be experiencing a sense of déjà vu as he seeks to sell parts of his empire. After all, he spent the better part of the 1990s disposing of various businesses that his family owned. From soft drink bottling to power generation to aluminium foil manufacturing, he closed and sold everything in order to focus his resources on just the newspaper business.

That focus proved shortlived though. After Deccan Chronicle’s successful IPO, the group once again ventured into newer and completely unrelated businesses.

There was Odyssey, the bookstore chain it acquired for Rs 61 crore in 2005. In 2007, KPMG, as part of a study commissioned by Deccan Chronicle, projected that Odyssey’s revenues could reach Rs 323 crore and EBITDA profit margins of over 16 percent within just two years. The number of stores too was slated to go up from 19 to 173.

Two years later, Odyssey’s actual revenue was just Rs 80 crore and its profit margin less than 2 percent. At present the chain is down to its last six stores.

Sieger Solutions was another subsidiary set up in 2007 to perform the rather curious job of buying Deccan Chronicle’s own ad inventory and selling it to advertisers for a profit. It was also to be the vehicle for Deccan’s expansion into newer areas, like online advertising, online subscriptions and alternate media platforms.

At one point in 2008, the company claimed it was in talks with the New York Times Company to sell a 5 percent stake in Sieger at an asking valuation of between Rs 1,500-1,800 crore. Sieger’s annual revenue at that point was Rs 71 crore which fell in the subsequent year to just Rs 44 crore.

There were many others, including Asian Age, the newspaper headed by veteran journalist MJ Akbar, which Deccan in 2005 estimated would contribute between Rs 75-100 crore to its revenue within two years two ventures in aviation, Aviotech, a chartered flight service, and Flyington Frieghters, a cargo airline and Netlink, a software development company.

One by one, all of them have failed miserably and have had to be folded back into the parent company.

Besides, how long the Reddys can continue their circulation-driven growth strategy remains to be seen. They don’t have the money to keep printing tens of thousands of copies of newspapers in cities like Bangalore and Chennai where the readership doesn’t appear to be keeping up, nor are advertisers paying anywhere near the premium rates Deccan Chronicle had expected, according to the senior media buyer quoted earlier.

“I am used to battles. In Andhra, I was to be obliterated, first by The Hindu, then by Indian Express, followed by Newstime, and The Times of India, but I survived all that,” said Venkattram Reddy in a November 2005 story in Business Standard.

But no one told him that surviving his own decisions would be the toughest of all.

First Published: Sep 05, 2012, 12:15

Subscribe Now