That is the professional opinion of Joel Myers, the CEO of AccuWeather, about the weather on Mother’s Day in New York City, as rain pelts the pavement nonstop and temperatures drop into the 40s. From the corner of 50th Street and 3rd Avenue, he shoots a text to company headquarters in State College, Pennsylvania, suggesting employees use the word in the day’s New York forecast. “I’m always looking for ways to make the information we communicate better and more accurate,” he says.

Wiry and fit at 79 with a full head of dyed brown hair, Myers runs America’s oldest independent private weather forecasting company. He founded it in 1962 while studying for his master’s in meteorology at Penn State. His first client, a local gas company, paid him $150 to forecast three months of winter weather so it could plan for home heating demand.

Today, conservative estimates of AccuWeather’s annual revenues exceed $100 million. Customers include hundreds of TV and radio stations across the country plus major print outlets like the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal and USA Today. More than 1,000 companies use Accuweather’s private weather forecasts to improve their bottomlines. Those range from the obvious—railroads and amusement parks like Six Flags—to the less obvious—say, Clemson University’s campus police department, and Starbucks.

In all, the business could be worth as much as $900 million, and Joel owns more than half of it, with the rest split among company executives and employees, including his youngest brother, Evan, who serves as COO. Joel’s other brother, Barry, who was AccuWeather’s CEO until January, recently sold his small stake for $16 million after being nominated in 2017 by President Donald Trump to head the $5.4 billion (2019 budget) National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

For decades, private weather forecasting has been a cosy industry, dominated in the U.S. by AccuWeather, the Weather Company (founded as the Weather Channel in 1982 and bought by IBM for $2.3 billion in 2016) and DTN, which focuses on industrial concerns and was purchased by a Swiss holding company for $900 million last year.

But now a perfect storm of macro-trends—cheaper processing power, cloud computing, vastly improved AI and a proliferation of low-cost sensors—has opened up the field to a fresh crop of ambitious startups. In aggregate, they have raised hundreds of millions of dollars from investors, who think the incumbents look vulnerable to creative new business models.

They are fighting over a big and growing pie. Recent numbers are hard to come by, but a 2013 study from the Wharton School estimated that overall revenues for climate and weather companies were about $3 billion and that, in aggregate, the industry was worth some $6 billion. A 2017 report from the National Weather Service included a prediction that the sector could quintuple in size.

“Every time we turn around, a different market cracks open,” says Glen Denny, head of enterprise solutions at Baron Services. The 29-year-old firm in Huntsville, Alabama, which manufactures $1 million Doppler radar units, has been beefing up its custom forecasting business.

The possible applications are nearly endless. Take Nascar races, which are halted in the event of rain. At a recent event at Michigan International Speedway, Chevy driver Austin Dillon skipped a pit stop and placed first when a downpour cut the race short. His secret weapon? A private IBM forecast that alerted him to the likelihood of precipitation. “We get turn-by-turn forecasts within a quarter of a mile on the track,” says Pat Suhy, manager of the Chevrolet Nascar Competition Group, which pays more than $100,000 a year for its forecast subscription.

The impact grows with the size of the concern. At Xcel Energy, a Minneapolis utility with $11.5 billion in annual sales and a big wind-power division, saved its customers more than $60 million in fuel costs over seven years using private forecasts from Boulder, Colorado-based Global Weather Corp.

Each private forecaster starts with freely available information from the National Weather Service, then most add their own data sources, collected using cheap sensors deployed on everything from seafaring drones to, in Xcel’s case, its wind turbines. That data is then fed into custom algorithms and weather models, often underpinned by rapid advances in AI and machine-learning.

“It’s not only easier to collect massive amounts of data more and more quickly and run models on that data, it’s easy to disseminate the results quickly,” says Eric Floehr, the 49-year-old founder and CEO of ForecastWatch in Dublin, Ohio, regarded as the J.D. Power of weather prediction. “There is just more experimentation.”

*****

Among the many weather-related startups, three stand out because of the money they’ve raised the innovative ways they are gathering, evaluating and selling weather data and the scope of their ambitions.

![g_119015_saildrone_280x210.jpg g_119015_saildrone_280x210.jpg]()

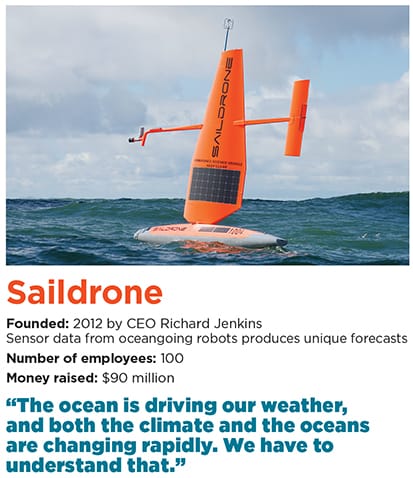

The most audacious may be Saildrone, founded by Richard Jenkins, 42, in Alameda, California, in 2012. A mechanical engineer and sailor, he studied engineering at Imperial College, London, before spending a year on the open water, including a stint as a crew member on a yacht owned by the Italian tycoon Gianni Agnelli. Two years into his degree, Jenkins started building a contraption called a land yacht, with a tubular carbon-fiber cockpit and three race-car wheels, topped with a 40-feet sail. In March 2009, he zipped across a dry lake in the Mojave Desert, hitting 126.2 mph and setting a world record for wind-powered speed.

That experience incubated the idea of creating an armada of oceangoing robots with a design similar to his land yacht. He formed Saildrone as a research project that would produce a fleet of 23-feet-long, 15-feet-high unmanned vessels, each equipped with up to 20 meteorological and oceanographic sensors. At first, he says, his idea was to collect data on ocean acidification, temperature and salinity and use it for the “greater good.” His first customers were government agencies like NOAA and NASA.

By 2017, Jenkins realized that Saildrone’s robots were gathering a unique and powerful data set that could factor into superior weather forecasts. After all, most weather forms over the oceans, where there are few weather stations to notice it. Though it only has 25 robots deployed, he says Saildrone is already selling forecasts to sports teams, insurance companies and hedge funds.

![g_119017_jupiter_intelligence_280x210.jpg g_119017_jupiter_intelligence_280x210.jpg]()

More than a half dozen investors, including the foundation run by former Google CEO Eric Schmidt, are backing the company with $90 million in venture capital. Pitchbook pegs its value at $260 million. Employee head count is at 100 and growing. In January, the company launched a free weather app and plans to charge for a premium version starting in June. Cheap computing power allows Saildrone to quickly test powerful weather models. But its vast trove of sensor data makes it a novel challenger to AccuWeather and its ilk. “We have a unique data source that they don’t have,” Jenkins says.

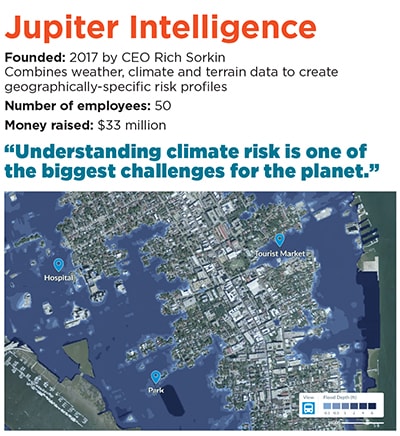

Other startups take weather data and go several steps beyond forecasting. Two-year-old Jupiter Intelligence, based in San Mateo, California, with offices in New York and Boulder, Colorado, combines weather data with information about an area’s environment and terrain to create “climate risk assessments.” It sells two services, short-term predictions of one hour to five days and long-range projections that look up to 50 years into the future.

Jupiter hopes that major cities planning for hurricanes, floods and fires, like Houston and Los Angeles, will eventually become customers, but in the short run businesses affected by severe weather seem like surer sells. Any company with a warehouse in a low-lying area wants to know how many square feet it might lose to sea-level rise and when that loss might happen. The company’s insurer wants to know that too. QBE, a big Australian insurer, is already a Jupiter customer, as is Nephila, an insurance-focused investment firm. Both are also investors who have contributed to the company’s $33 million in backing.

“IBM and AccuWeather predict the weather,” says Jupiter founder and CEO Rich Sorkin, 57. “We predict the impact of that weather.” Jupiter charges $200,000 to $500,000 to run a pilot for new clients. Yearly subscriptions cost $1 million and up. Revenue to date is in the single-digit millions he says, but he projects ten times that for 2019.

A Yale grad with an MBA from Stanford who started his career as a management consultant, Sorkin ran Elon Musk’s first breakout venture, Zip2, which developed online city guides, before it sold to Compaq for $300 million in 1999. In 2008, he made a first attempt at a startup to sell weather forecasts to businesses. His idea was to take publicly available meteorological models, pump them up with computing power and sell 30-day forecasts to energy commodities traders. But the forecasts were no better than the competition’s. He raised only $1 million for the company, Zeus Analytics, and it went out of business in 2011.

Jupiter looks more promising. The 50-person team includes talent from the federal government’s National Center for Atmospheric Research and NOAA. Like Zeus, Jupiter uses government-issued weather data, but Sorkin says artificial intelligence and detailed terrain-based information are producing risk projections that customers are willing to pay for. Without cloud computing, he says, Jupiter wouldn’t exist.

![g_119019_climacell_280x210.jpg g_119019_climacell_280x210.jpg]()

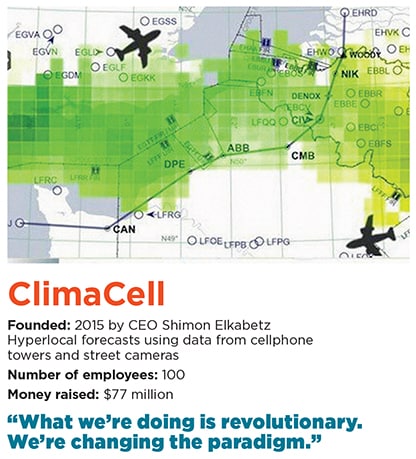

Another challenger with huge ambitions: ClimaCell, co-founded in 2015 by Shimon Elkabetz, 32, a former Israeli air force pilot, while he was earning his MBA at Harvard. When he was in the military, he nearly lost control of his plane after a forecast failed to warn him that he was about to fly into a thick bank of clouds. At the time, he thought to himself, “Someone has to come up with a new tool.”

Together with two co-founders, he developed what he says are minute-by-minute, hyperlocal forecasts that he claims are 60 percent more accurate than those of competitors. ClimaCell’s edge, according to Elkabetz: In addition to the government weather data all the private forecasters use, it pulls weather inputs from new sources like cellphone signals and street cameras. “We call it the weather of things,” he says. “We turn everything into a weather sensor.”

The company has raised $77 million in venture capital, valuing it at a reported $217 million. In just the past year, Elkabetz has opened offices in Tel Aviv and Boulder, Colorado, to supplement his Boston headquarters. He is taking dead aim at many of the industries that AccuWeather serves. “We want to become the biggest weather technology company in the world,” he says.

Already, ClimaCell is making ground-operation forecasts for airlines including JetBlue, which is also an investor, and game-day forecasts for the New England Patriots. Via, a ride-sharing company, uses its forecasts in five cities including London and Amsterdam. On a Sunday in mid-May, Via got an alert from ClimaCell about heavy rain in New York that would last from late morning to midday, with varying intensity in different parts of the city. Knowing demand would spike, Via made sure it had enough drivers in the wettest spots. “There is a significant monetary value to us in using ClimaCell’s platform,” says Ari Luks, Via’s director of global marketplace economics.

Can ClimaCell best the incumbents? Marshall Shepherd, director of the University of Georgia’s atmospheric sciences program and a past president of the American Meteorological Society, says he’s yet to see robust statistics proving the company’s claims, but adding lots of new data inputs could help produce more accurate forecasts. “I’m bullish on what they’re doing,” he says.

Others are skeptical. “ClimaCell makes a lot of claims, but I’ve never seen proof of anything,” says Clifford Mass, a longtime University of Washington atmospheric sciences professor. “Street cameras are not going to improve weather forecasting.” Elkabetz counters that prospective customers are given proof of its claims.

ForecastWatch’s Eric Floehr is as close as it comes to an expert with a broad view of the private forecasting business. He says the jury is out on Saildrone, ClimaCell and Jupiter Intelligence. What about ClimaCell’s assertion that its forecasts are 60 percent more accurate than the competition’s? “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence,” he says.

*****

Criticism of AccuWeather has been heating up since Trump nominated Barry Myers to head NOAA. Widespread reports have alleged the company engaged in a multiyear effort to push the government out of providing free weather forecasts. Joel Myers angrily denies it, “That’s a bunch of bullshit,” he fumes. “Nobody was trying to restrict the role of the National Weather Service.”

He also flatly denies that harassment took place at AccuWeather, despite the fact that the company paid $290,000 in 2018 to settle a Department of Labor investigation that found “widespread sexual harassment at AccuWeather.”

Less easy to dismiss is the pack of hungry competitors that are looking to eat AccuWeather’s lunch, though Joel tries to with a blanket “I’m not going to sit here and talk about competitors” before allowing, in a later interview, that “Everything is accelerating. Any business leader who says he knows what the world will look like in 20 years is making it up.”

Where AccuWeather will be in 2039, when Joel is 99 years old, is anyone’s guess. The company won’t discuss specifics of its succession plans, and none of Joel’s seven children are involved with the business day-to-day. The Myerses are surprisingly sanguine about the future.

“Eighty is the new 60,” Barry says. “Joel’s an energetic guy. He’s working 24-7, and he loves what he does.”

“I’ve seen lots of new companies come along,” Joel says. “Some of them will find a niche, and some of them will fail.”

Joel Myers, founder and CEO of AccuWeather, believes that his Pennsylvania-headquartered weather forecast company did big data before it was big data and “AI before it was called that.”

Joel Myers, founder and CEO of AccuWeather, believes that his Pennsylvania-headquartered weather forecast company did big data before it was big data and “AI before it was called that.”