Forbes Investigation: Fintech's secret bank

Many of the most popular finance apps are little more than glitzy loan pushers with a voracious appetite for risk. Enabling them is a tiny bank in New Jersey with overinflated ambitions

.jpg?im=Resize,width=600,aspect=fit,type=normal)

.jpg?im=Resize,width=600,aspect=fit,type=normal)

Through the Looking Glass: Cross River CEO Gilles Gade says his New Jersey bank will provide the operating software for finance’s future

Through the Looking Glass: Cross River CEO Gilles Gade says his New Jersey bank will provide the operating software for finance’s future

Image: James Toppin for Forbes

If you want a glimpse of the future of banking, don’t look to Silicon Valley or Manhattan’s financial district. Instead, drive across the George Washington Bridge to Fort Lee, New Jersey. If you glance left as you come over the traffic-clogged expanse and make your way onto Interstate 95, you’ll see a red granite office building. On its 14th floor, overlooking America’s busiest toll plaza, is the headquarters of a tiny FDIC-insured bank named Cross River.

Cross River is not a typical community bank. There are no tellers here, or ATMs or safe deposit boxes. Instead there are 175 bank staffers and traders stuffed elbow to jowl into about 23,000 square feet, peering into hundreds of computer monitors—often stacked three per desk. There are startup touches—a kitchenette stocked with LaCroix sparkling water, gourmet coffee and a game room.

Cross River is on a lending tear. It is underwriting loans at the rate of more than $1 billion a month—some $30 billion worth in just nine years. But unlike in banks of yesteryear, virtually all Cross River’s lending officers aren’t human beings. They are apps. Cross River’s loans originate mostly from 15 or so buzzy venture-capital-backed financial technology startups, so-called fintechs, that go by names like Affirm, Best Egg, Upgrade, Upstart and LendingUSA. The fintechs provide the customers Cross River provides the licences and infrastructure. It holds 10 percent to 20 percent of each loan it issues, and the massive volume of fintech loans has propelled Cross River to $2 billion in assets, up from $100 million a decade ago.

“We’re in the moving business, not the storage business,” booms chief executive Gilles Gade, 53, an immigrant from France, balding and wearing clear-framed glasses and a navy Hugo Boss sweater. “We move assets. We originate [them], we package them, and we sell them.”

Gade is being modest about Cross River’s role in the fintech revolution. State-chartered banks like his have the regulatory and compliance framework in place and the lending licences necessary to originate loans. Most fintechs do not and thus rely on banks for funding. It’s the industry’s dirty little secret. Once you get beyond the slick iPhone apps and inflated tales of big-data mining and AI-generated lending decisions, you realise that many fintechs are nothing more than aggressive lending outfits for little-known FDIC-insured banks.

Since 2010, Silicon Valley venture firms and others have invested some $175 billion to disrupt the financial system, according to Accenture. This has inevitably resulted in astronomical valuations for many privately held fintechs. But just as WeWork’s prospectus laid bare the fact that the company was little more than an overpriced lessor of real estate, a glance under the hood of many fintechs reveals similar sleights of hand.

Take out a $2,000 zero-interest, 39-month installment loan from Affirm to buy a Peloton bike this Christmas and it is likely that Cross River is actually making the loan. Cross River holds onto such loans for a few days, then transfers them to the fintech, which will sell the debt to hedge funds and bond buyers, or securitise it into bundles of thousands of such loans. Image: Jamel Toppin

Image: Jamel Toppin

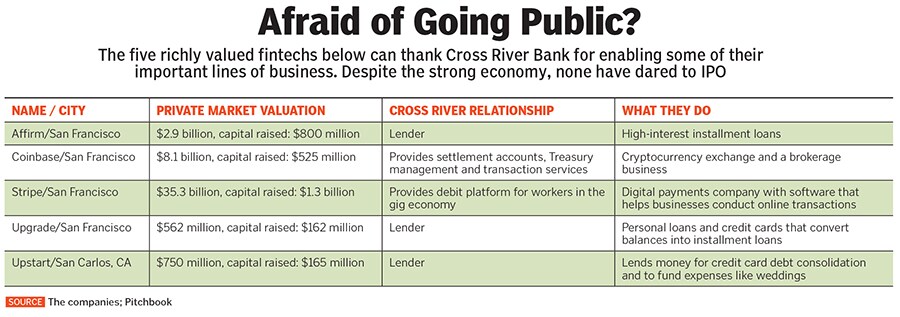

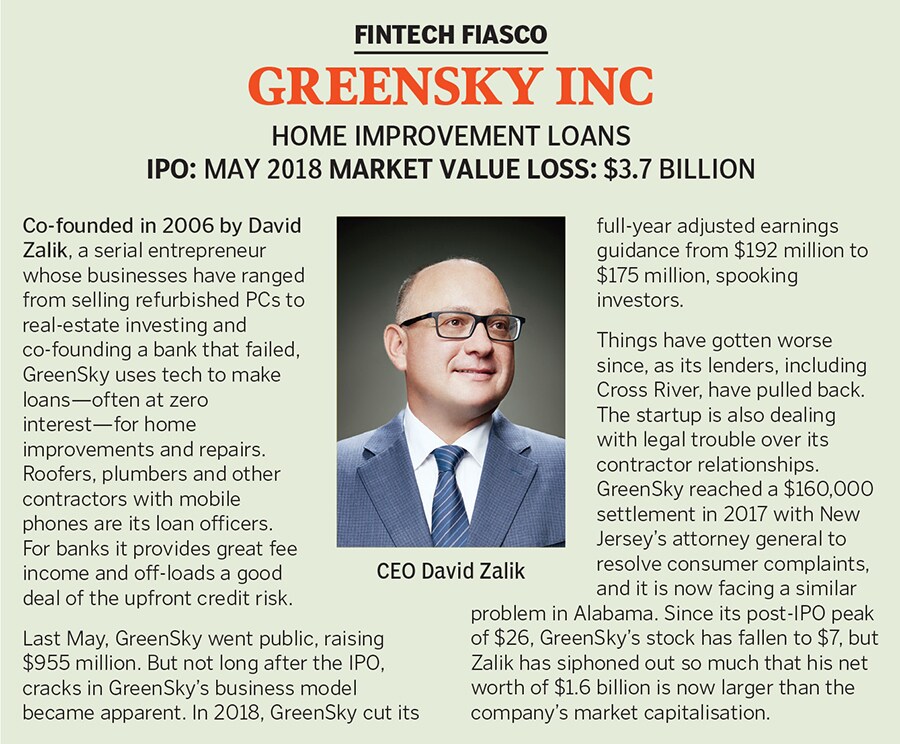

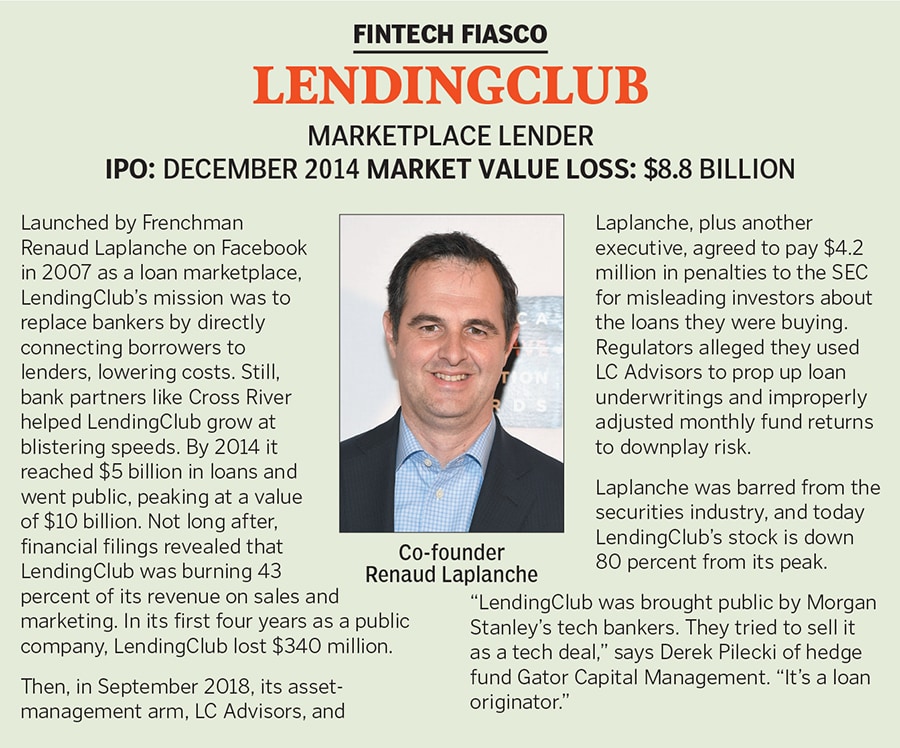

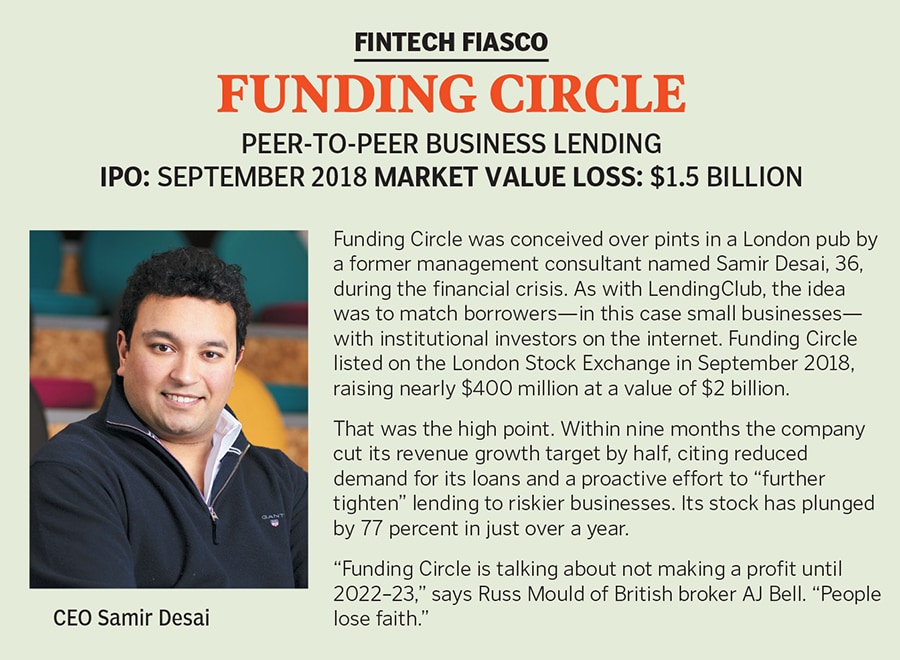

On the stock market, banks tend to trade for a fraction of the multiple technology stocks do. That’s why fintechs are eager to position themselves as tech firms, not financial firms. The VCs are eager to sell that story, but the market hasn’t been that stupid. Many fintech unicorns that have managed to stage public offerings have been severely punished in the aftermarket. LendingClub went public in 2014 with a valuation of $5.6 billion. Today it is worth $1.2 billion. On Deck Capital, a fintech that makes superfast small business loans, is worth $290 million today, down from $1.9 billion the day it IPO’d in late 2014. It’s a similar story for other fintech IPOs like Funding Circle and GreenSky.

“[These] companies positioned themselves as tech companies, [but] in reality [they] are just leveraging tech to further an old-school business solution like consumer lending,” says Andrew Marquardt of Middlemarch Partners and formerly of the New York Fed and BlackRock. “You have investors looking at it and saying, ‘This is a bank, it is not a tech company.’&thinsp”

By Forbes’s count, some $15.6 billion in market value has already been wiped out thanks to ill-fated fintech public offerings. Other large lenders like Prosper Marketplace and LoanDepot have either filed to go public and abandoned plans or remain private. More inflated valuations are hiding in plain sight.

All of this could eventually spell big trouble for Cross River. Some fintechs it has done business with, like GreenSky and LendingClub, have already become investor fiascoes (see sidebars). There may be more train wrecks coming (see table). Five of its biggest fintech clients by market value have raised $2.25 billion at a combined value of $50 billion. None seems ready to undergo the scrutiny of a public offering even as the stock market hits highs and consumer defaults remain near record lows.  Image: Getty Images

Image: Getty Images

At the moment, though, it’s boom time in Fort Lee. But the party could end fast. Filings with the FDIC show personal loans—virtually all from fintech lending partners—account for a high 60 percent of the loans on its books. A good deal of the loans Cross River carries have sky-high interest rates, forbidden in states like New York and Connecticut with strict usury laws. The bank itself is venture-funded, attracting money from the likes of Andreessen Horowitz and Battery Ventures—some $28 million in late 2016. A year ago, KKR & Co. led a $100 million investment round, valuing Cross River at nearly $1 billion, roughly three times what a similar-size regional bank would typically be worth.

“Our strategy is to be the only financial services provider to the fintech ecosystem globally,” Gade says excitedly. “Changing people’s lives is why we do this, before anything else.”

Prior to his arrival at Cross River, Gade had a conventional career. He’d done stints at Bear Stearns and Barclays and as CFO of New York mortgage lender First Meridian, known for issuing loans under the licensed name Trump Financial. Early in his career, Gade, who was born in Paris, took two years off to study the Talmud. In 2008, he decided to make his move, pooling some $700,000 in savings with $9 million from friends and others to invest in Cross River, a community bank that had received a bank charter but had no assets.

During Cross River’s first year in operation, Gade and his small team mostly traded in and out of government-backed and auction-rate securities. Then, less than two years after the bank opened, Gade was approached by David Zalik, an entrepreneur whose fintech, GreenSky, was growing rapidly by enlisting contractors to make no-interest loans to property owners for home improvement projects. Image: Getty Images

Image: Getty Images

Gade began originating loans for GreenSky and realised the nascent fintech could become Cross River’s engine for growth.

Gade quickly refashioned Cross River to serve the fintech’s interests. His timing was perfect. It was 2010, and the financial crisis had created widespread distrust of traditional bankers, consumers had little equity to tap in their homes and banks largely stopped extending credit. Cross River and several other specialty banks like Utah’s Celtic Bank and WebBank were eager to fill the void, through a growing field of fintech frontmen.

The rise of fintechs has some benefits. By tapping data and using behavioural economics, many of the new companies, like Acorns and Betterment, have increased savings rates and made personal finance more efficient. Fintechs have been responsible for some $170 billion in refinancings and loans to date.

Everything was going smoothly for the sector until about 2015, after a handful of big outfits like LendingClub went public. Suddenly investors outside of Silicon Valley began to scrutinise the books—and they saw cracks in their foundations.

Today Cross River continues to expand, seemingly oblivious to the looming risks. Just as banks competed in a frenzy to issue “low doc” and low-rate mortgages while the housing bubble inflated, some fintechs have begun making riskier loans. Image: Getty Images

Image: Getty Images

Last year, one of Cross River’s biggest fintech partners, Freedom Financial, agreed to a $20 million settlement with the FDIC after the regulator determined Cross River used “unfair and deceptive” practices by failing to effectively oversee its partner during the origination of over 24,000 loans. Cross River was forced to pay a $641,750 fine.

An even bigger threat to fintechs is an economic downturn.

In the third quarter of 2019, Cross River reported that its problem loans doubled to nearly 2 percent of total, led by a $17 million problem in commercial real estate, where 10 percent of its assets were past due. (Cross River says most of the loans are now current.) But since the fall of 2016, Cross River’s provision for loan losses has nearly doubled as a percentage of average loans. Even more recently its reserve coverage ratio of “past due or nonaccrual” loans has declined from 489 percent to 114 percent. This at a time when the overall environment for credit—thanks to record-low unemployment and low interest rates—is ideal.

“Our revenues have had a compounded annual growth rate of 45 percent,” says Gade, who has adopted Silicon Valley speak to describe his operation as an “everything as a service” company. “The talk about a recession or a credit cycle that’s going to start going the other way is much ado about nothing.”

First Published: Mar 11, 2020, 18:01

Subscribe Now