How Solar Panels Work Without Human Force

Solar panels have gotten so cheap that installlers are seeking new ways to push down the cost per clean kilowatt. One answer: Get rid of the humans

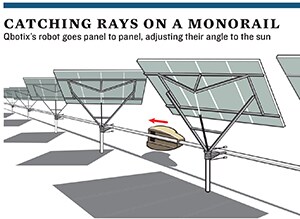

Behind a high fence in Menlo Park, California, a grey, tuna-shaped robot glides on a monorail around 20 solar panel arrays attached to steel poles, like WALL&bullE on a Disneyland ride. The Solbot, made by startup QBotix, stops at each array and extends a cylindrical arm to adjust the angle of the photovoltaic (PV) panels so they capture the most amount of sun as it moves across the sky and through the seasons.

Meanwhile, in Germany, a giant robotic arm that looks like it escaped from an automotive factory and mated with an army tank rumbles through a field, plucking 300-pound solar panels from a pallet and installing them on steel racks. The robot is called Momo, and two of them can do the work of the 250 labourers needed to build a 100-megawatt PV power plant, its creator claims.

Solar power’s race to become competitive with fossil fuel has been aided hugely by the steep price drops in recent years for PV modules. Down 40 percent in the past year, PV modules now account for only about a third of the cost of a power plant. That has left developers scrambling for other ways to cut costs. “To be honest, there hadn’t been that much innovation happening,” says Martin Simonek, a solar analyst with research firm Bloomberg New Energy Finance in London. “There’re only so many ways you can put panels on the roof or the ground.” So attention turned to such things as streamlining permitting and other paperwork and reducing the number of nuts and bolts needed to assemble a solar array.

Boring. It’s time to welcome our new robotic overlords, as startups like QBotix exploit advances in sensor technology and automation to cut solar power plant costs.

“We are the first company to bring robotics to the operation of solar power plants,” says Wasiq Bokhari, QBotix’s boyish 42-year-old chief executive. “Much of the cost of a solar plant is the steel. The robots allow us to take out 50 percent of the steel used in the system.”

That lets a solar developer install QBotix’s dual-tracking robotic system for the same cost as a simpler single-axis tracking system that produces less electricity. “The robot itself costs only a few cents a watt,” notes Bokhari, a physicist and serial entrepreneur, who has raised $7.5 million in funding from investors that include NEA, Firelake Capital, Siemens Venture Capital and DFJ JAIC.

QBotix is selling its systems—they declined to reveal the price—in 300-kilowatt units that include a robot, a backup robot, a steel track and tracking stands for the solar panels. The bots run on lithium-ion batteries and can adjust 200 solar panel arrays in 40 minutes for about 30 cents of electricity a day, according to Bokhari. The QBotix system does not require land to be level or graded. And developers don’t have to dig trenches to bury a power plant’s wiring, as it runs in a conduit alongside the QBotix monorail. “You could install it on the side of a hill, and the racks can follow the contour of the hill,” says Bokhari, who has recruited solar experts and roboticists from Stanford, Caltech and MIT.

“If you can boost electricity production by 20 percent at a solar plant, that’s huge for an operator or utility,” says Michael Butler, a veteran clean-tech investor who runs Cascadia Capital in Seattle.

One early QBotix customer is Sol Orchard, a solar power plant developer based in Carmel, California. Sol Orchard Chief Executive Jef Brothers plans to install the QBotix system at a 1-megawatt research station he is building in the southern California desert in collaboration with San Diego State University. “If it works as well as they claim it will work, I’m interested in using it at other installations,” says Brothers. “It all comes down to how acceptable it will be to the bankers.”

The pinstriped-suit set tend to be conservative, particularly when it comes to financing renewable energy projects that deploy new technologies. “Tracking systems haven’t been a popular choice because banks don’t like them, as they generally don’t like black boxes or moving parts in solar systems,” notes Simonek.

But they might like Momo. The robot, developed by German engineer Bernd Brodbeck and Kiener Maschinenbau, a manufacturer of automated industrial systems, is a tool to build solar power plants rather than operate them. It uses 3-D cameras and other sensors to pick up large solar panels and place them on mounting racks. “In a big PV plant, you have to assemble thousands of modules,” says Brodbeck. “That’s not economical, so we took the industrial robot outside and put it in the field.”

He estimates that it would take only four workers and two of the $900,000 robots to install solar panels on a 100-megawatt project. Kiener has sold one of the robots to German solar power plant builder PV-Kraftwerker, which is testing the machine at one of its projects, and is talking to developers in Europe and the US.

“That’s very innovative,” says Simonek. “But I wouldn’t underestimate the need for human labour. There’s a huge emphasis on quality control that can’t be eliminated by robots.”

In other words, there still might be a place for people under the sun.

First Published: Dec 10, 2012, 06:49

Subscribe Now