How to make $1 billion in your spare time

Practising dermatologists Katie Rodan and Kathy Fields have built a remarkable $1.1 billion fortune with two hugely successful skincare brands—and a whole lot of cringe-worthy marketing methods

Ten thousand fashionably dressed women are packed into a convention centre in Austin, Texas, waiting. Suddenly, the dark room explodes with disco lights as Dr Kathy Fields and Dr Katie Rodan emerge. Wearing black leather dresses with sparkling accents, the two hold hands, beaming as they stride to centrestage. “Wrinkle warriors!” Rodan shouts, leaning forward and cupping her hands around her mouth. “Are you ready to change the game?” The crowd goes wild as the duo does a little victory dance.

Fields, 58, and Rodan, 60, are rockstars to those who gathered last September at the annual convention for Rodan + Fields, the doctors’ line of anti-ageing skin care products. But this is hardly their first skin care success story—or even their full-time job. More than a decade before starting Rodan + Fields in 2002, the two practising dermatologists teamed up to create acne treatment Proactiv. Now, two days a week, they still trade their glamorous garb for white lab coats to treat patients at their respective Bay Area dermatology practices, where, some say, the wait time to become a new patient can be over two years.

Today, Fields and Rodan’s skin care company doesn’t just bear their names it presents the women themselves—their bubbly personalities, clear, foundation-free skin, close bond and self-made success—as embodiments of everything Rodan + Fields’ 150,000 independent “consultants” aspire to be. The founders believe they are providing their consultants with the chance to emulate their success. “Let’s empower the entrepreneur,” Rodan says, echoing lessons she learned from her father, a no-nonsense judge. “You have to be able to stand on your own two feet. I feel like we’re really delivering that message to a lot of people, especially women, who maybe never saw that opportunity.”

The Rodan + Fields pitch is about more than just the allure of anti-ageing creams. The company’s independent reps also sell the dream that any woman can easily achieve financial independence and success by becoming a Rodan + Fields saleswoman. “This is an opportunity for women to have it all,” Fields says. But the truth is that the dream is financially out of reach for the vast majority who sell Rodan + Fields products. According to data from its 2015 income disclosure, 42 percent didn’t get a single paycheque last year.

That reality hasn’t slowed Rodan + Fields’ blistering growth. For the past six years, revenues have surged an average of 93 percent a year, growing from $24 million in 2010 to $627 million in 2015. Fields and Rodan are quick to say they are doctors, not businesswomen, but their success at building not one but two lucrative skin care brands has landed them on Forbes’s list of America’s Richest Self-Made Women for the second year running each has an estimated net worth of $550 million. And they’re moving quickly to take their part-time empire global.

Kathy Fields stepped onto Stanford’s campus in 1984 for her dermatology residency, straight from the University of Miami medical school, wearing a white skirt and sky-high, hot-pink pumps. Her classmates wore pleated Dockers and frumpy button-down shirts. The exception was fellow resident Katie Rodan, who had come north from USC School of Medicine in Los Angeles. “&thinsp‘Rhinestone Rodan’ was my name,” Rodan says, laughing. “That kind of says it all.” The two bonded instantly over their shared fashion sense and solidified their friendship as they studied for exams. They stayed friends as they joined separate all-male dermatology practices in the San Francisco Bay Area.

In 1989, after a particularly long day treating patients, Rodan had an idea to create the acne product she wished she could prescribe. The first person she called was Fields. Both doctors were frustrated by the lack of new acne treatments. Drug companies took the view that the market was too small for the research investment it required, which meant that the only options were ineffective spot treatments with strong chemicals. “It would be like a dentist saying, ‘Don’t brush all your teeth—just brush the tooth with the cavity,’&thinsp” says Fields. “It didn’t make sense to us as dermatologists.”

It’s one thing to see a gap in the market, another to create a product to fill that gap—without quitting your day job—and turn it into a household name. What the pair had going for them was their dermatological expertise. “We knew this market, and we knew it better than anyone else,” Fields adds. As for the rest, they had to learn the hard way.

The pair dragged everyone they knew with business chops to dinner and tapped Rodan’s husband, Amnon, an MBA from Harvard, for advice. (He is now chairman of the company’s board.) Once, the doctors took an aesthetician they knew out for sushi, hoping her experience mixing face masks would translate into insights. When she gave them a blank stare, Fields and Rodan realised that what they actually needed was a cosmetic chemist, and they soon hired one as a consultant.

In 1990, the two women signed a five-sentence contract declaring themselves “50-50 partners” in a company created to make an acne treatment. The contract, which now hangs in a cheap frame in Rodan’s home office, marked the official beginning of their business partnership. “We shared the dream,” Fields says. “It’s not how different we are, it’s how alike we are.” They worked as a team. When Fields was on bed rest during a difficult pregnancy in 1994, Rodan covered for her, handling all business issues. Thirty-two years after they first met, the doctors remain close, laughing at inside jokes and finishing each other’s sentences. They share an office at the Rodan + Fields headquarters in San Francisco and always appear together in photos, often in matching white coats.

The thing the founders lacked was capital. One telling line of their contract: “All expenses over $50 must be approved by both parties prior to incurring expense.” At times, spending $100 on a prototype would have maxed out their diaper budgets. “It really tells you we were broke,” says Fields.

Armed with a formula, Rodan’s friend Judy Roffman, a market researcher, helped them test their product on a group of strangers. The initial reaction wasn’t good. The group complained about the smell and feel of the product. So Rodan and Fields started focusing on the consumer, instead of just the medication, creating a product that felt like a high-end beauty cream but contained the acne formula.

“It was like a rat’s maze,” Fields says. “We kept turning down dark corners, and there was a lot of failure along the road to this ultimate success.” Most of the twists and turns happened in Rodan’s kitchen on nights and weekends. “That could’ve been the name of the company—Katie’s Kitchen!” Fields says, laughing. Outside of their circle of friends and advisors, they kept quiet about what they were doing for fear that someone would steal their idea.

In 1993, the dermatologists showed up at Neutrogena with plastic baggies of their new acne product, Proactiv. Nearly a year later, in 1994, Neutrogena president Allan Kurtzman told them that infomercials would be the way to go to market should Neutrogena acquire the brand. They were both horrified. “Does he think we’re this cheesy? We’re good girls. We went to Stanford, and we’re not going to do infomercials,” Rodan remembers thinking. Adds Fields: “They were icky.”

Soon after, Neutrogena turned them down. “It’s over. Those $50 cheques we spent are down the drain. Now what are we going to do?” Rodan remembers telling Fields in tears. Adds Fields: “It was our only hope because we’re not businesswomen, we’re doctors.”

But Neutrogena had actually given them something: A “cheesy” but powerful marketing plan. Not long after, at a conference, Rodan’s mother met an aunt of the co-founder of infomercial company Guthy-Renker. She provided an introduction, and talks began. In 1995, Fields and Rodan licenced their product to Guthy-Renker they had spent $30,000 of their own funds over five years, taking no outside investment. Guthy-Renker marketed and distributed the product, paying the doctors an estimated 15 percent in royalties from Proactiv sales. “We gave them our intellectual property and the name Proactiv. We were there as advisors,” Fields says. It was the right product at the right time. A 1984 ruling by the Federal Communications Commission eliminated certain regulations on television content, creating a boom in infomercials.

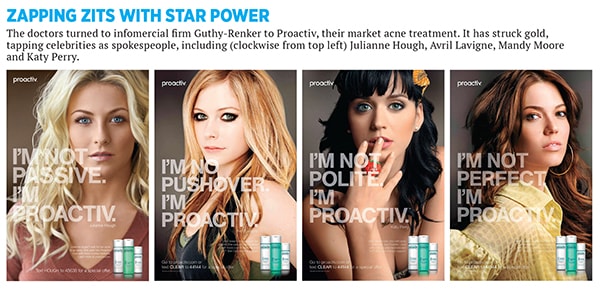

Proactiv quickly became one of Guthy-Renker’s most successful products, responsible for approximately half of the company’s sales. The acne treatment brought in a reported $1 billion in sales in 2015, thanks to celebrity endorsements from the likes of Justin Bieber and Vanessa Williams. Guthy-Renker continues to sell the treatment on a subscription basis online and in mall kiosks across the US. In March, Guthy-Renker entered into a joint venture with Nestlé to expand Proactiv’s international sales as part of the deal, Fields and Rodan sold their remaining rights to Proactiv royalties, getting a lumpsum that Forbes estimates to be more than $50 million.

After inking the initial Proactiv deal, Fields and Rodan could have gone back to just practising dermatology. But they continued to heed advice they had received back in residency: “Get a hobby, or you’ll be doomed to treating acne and warts.” The pair felt driven to solve people’s skin care problems. “Our motivation was solely for that need,” Fields says. “We didn’t dream of a business and an office.”

Both Fields and Rodan started noticing that younger and younger people were coming into their offices complaining about wrinkles. Their contract with Guthy-Renker allowed them to make other products as long as they didn’t market them on TV, so the pair set their sights on another market: Anti-ageing. They went back to the kitchen at night, mixing chemicals for new products.

In 2002, they launched the Rodan + Fields line, which they sold in department stores. The following year, cosmetics giant Estée Lauder bought the brand for an undisclosed sum. But, over time, it became clear to the doctors that Estée Lauder’s priority was its larger legacy brands. Rodan + Fields wasn’t getting the marketing push it needed. Frustrated, Fields and Rodan studied direct-selling firms like Nu Skin and tested that format by holding a Rodan + Fields party. A Los Angeles TV station covered the party and interviewed the doctors for a late-night news segment on direct selling. The station was flooded with calls from people wanting to get involved. So the doctors decided to buy back their brand in August 2007. “We knew we had products that worked and changed lives,” Fields says. “We were compelled to continue.”

Rodan + Fields has had a multilevel marketing structure ever since: Consultants are paid a commission for their own sales and for the sales of people they recruit. But unlike Avon and Mary Kay in their early days, this is multi-level marketing for the digital age Fields and Rodan like to call it “community commerce”. Salespeople don’t stock inventory. They work their online social networks to spread the word about Rodan + Fields. Instead of traditional parties, salespeople often hold virtual Facebook events and promote the products over the live-video streaming app Periscope.

Consultants sell lines of pricey anti-ageing products that address four different problem areas: Adult acne, wrinkles, sun damage and sensitive skin. Each regimen retails for $160 to $190 for a two-month supply and comes in a multi-step process—including cleanser, toner and skin cream—much like Proactiv. Because Rodan + Fields products are available over the counter, like Proactiv, they don’t need approval from the Food & Drug Administration, but the company says it complies with FDA guidelines for over-the-counter products.

While Fields and Rodan own the majority of the company, they don’t run it day to day they leave that task to CEO Diane Dietz. As members of the board, the doctors are free to focus on being the public face of the company and on guiding product creation. They once frustrated everyone at Rodan + Fields by vetoing a product that was close to launch because it didn’t meet their standards.

Consumer advocates decry multi-level marketing as one step away from a pyramid scheme. “Multi-level marketing has evolved to this point where it’s not illegal, but it’s unethical,” says marketing expert D Anthony Miles, pointing out that sellers at the top of teams build their success on the backs of those at the bottom, who have little chance of achieving the same level of opportunity.

Fields and Rodan try to differentiate themselves from a model that’s far ickier than infomercials. They claim their digital focus and emphasis on creating a close-knit consultant community set it apart from other direct-selling companies. They believe they offer the same opportunity to be independent entrepreneurs to a crowd of highly-educated women across the country, many of whom have had successful corporate careers and wouldn’t normally be attracted to multi-level marketing. Successful consultants revere the doctors and believe that their story of entrepreneurial success legitimises the business model.

The fact is most consultants aren’t making much money. Take Robin Gravlin, 53, of Granite Bay, California, who was a consultant from 2009 to 2011. A stay-at-home mom, Gravlin was looking for a part-time job that was worth her while. She says she worked about 20 hours a week and pulled in revenue of about $100 a month. After two years, she had lost some $3,000 because of the costs she incurred: Marketing materials, travelling and buying samples for promotional events. “They do have good products. Would I recommend someone selling it? No,” Gravlin says. “I think there are probably a lot more people who fail than succeed... They make it sound easy, but it’s not.”

There’s nothing wrong with joining a business with these odds, as long as you’re aware of them. When pushed, Fields and Rodan stress that it’s not easy to be a consultant and that very few become wildly successful. In practice, however, those financial realities are often obscured, as consultants market the business opportunities online and in presentations. One popular marketing tactic is a virtual Facebook event, during which consultants post their pitches for Rodan + Fields in the event invitation while attendees refresh the page. In an April event called “Rodan + Fields All In”, one slide highlighted Rodan + Fields’ purported simplicity: “We wash our face, talk about it, and get paid. That SIMPLE!” Another slide said, “As mentioned, many people are making full-time incomes.” Not mentioned: The fact that only 2 percent of active consultants make the minimum wage or more on an annualised basis.

Rodan + Fields isn’t much different in that regard from other multi-level marketing companies. Forbes studied the income disclosures of 16 others, including AdvoCare and Nu Skin. On average, only the top 3 percent of consultants got paid more than the minimum wage in annual gross income. At some companies, nearly 90 percent of consultants made nothing at all. The disclosures show that the only way to make a lot of money is to build a huge team to earn commissions off the sales of those you recruit.

Bridget Cavanaugh of Bozeman, Montana, is one of those very rare power sellers. Cavanaugh, a former PR executive, started selling Rodan + Fields products in 2009. She says her 5,000-person team includes consultants in every US state and Canadian province. Cavanaugh has been qualifying for trips with the doctors to places like Napa Valley, Maui, Paris and Bangkok since 2010, sometimes accompanied by her family. “This is really a family affair for us,” she says. “To be an entrepreneur every day while my children watch is rewarding beyond belief.”

Probably because of the hyperpositive marketing, more and more salespeople are signing up with Rodan + Fields each year. In 2008, after relaunching as a multi-level marketing company, Rodan + Fields had just 1,350 consultants today it has 150,000.

But this growth isn’t that unusual for multi-level marketing companies—until they saturate the market for those willing to enlist in what is almost always a futile effort to make a living.

The one cure for this saturation: International expansion. The mother of multi-level marketing, Amway, is in more than 100 countries: Over 90 percent of its revenue is estimated to come from outside the US. And that’s what Rodan + Fields is doing now. The company launched in Canada in February 2015 and says it achieved 300 percent of its profit forecast for 2015. Australia will be next, in 2017, and after that the company is setting its sights on the giant Asian market.

Sitting side by side, as is their wont, discussing their company’s future global expansion, Fields and Rodan clearly have no plans to slow down. In addition to seeing patients, they are both adjunct professors at the Stanford School of Medicine. “We have so much more we need to do,” Rodan says.

“We’re not going to sit on the beach, because it’s bad for your skin.”

First Published: Jun 28, 2016, 06:13

Subscribe Now