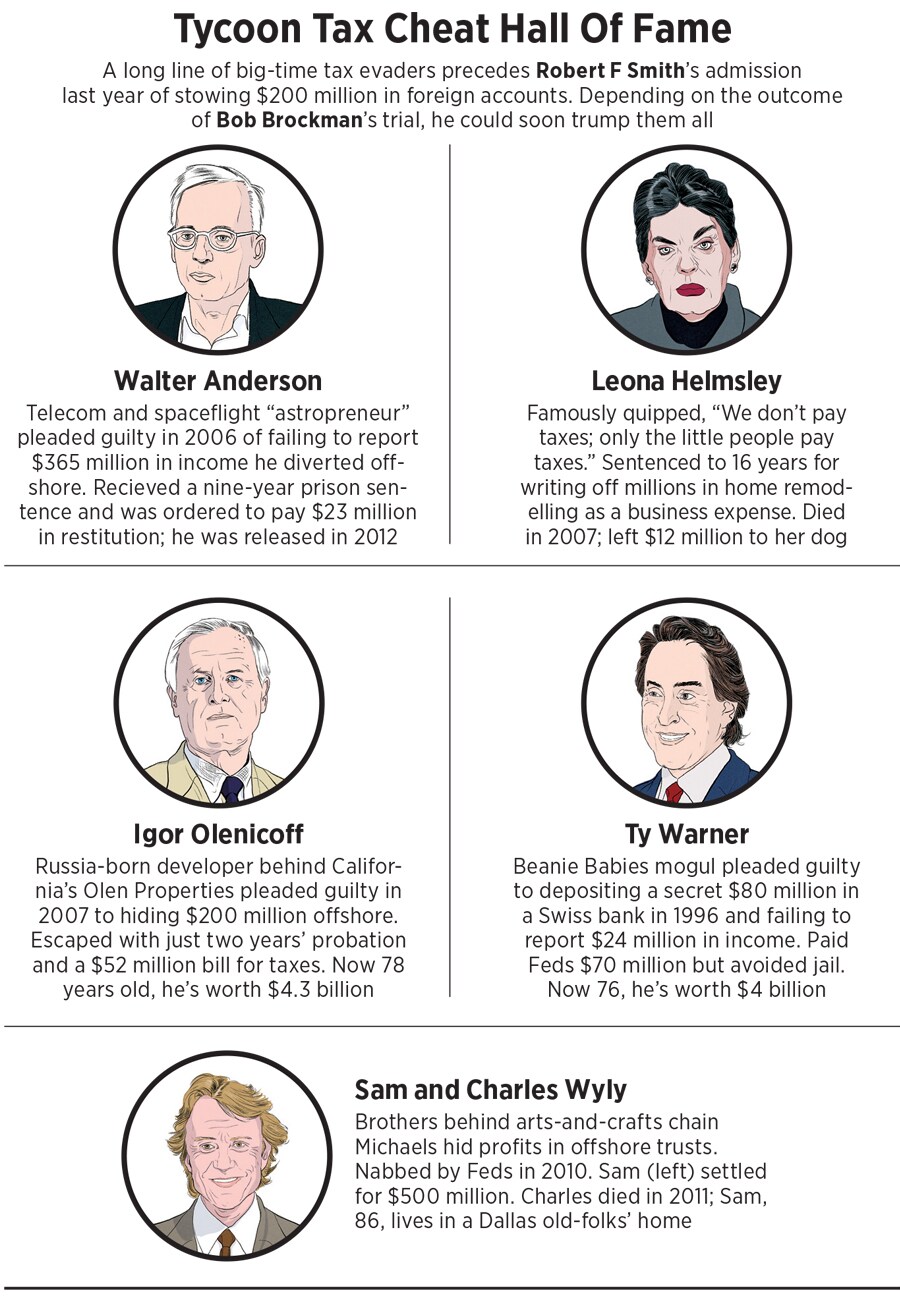

Meet America's most manipulative billionaire

The inside story of how Bob Brockman, the secretive billionaire who allegedly masterminded America's biggest tax-evasion scheme, used 'Darth Vader' contracts to overcharge auto dealers and finance Rob

Illustration: Emmanuel Polnaco[br]Ever since Ford Motor Company began selling its Model T in 1908, few pieces of technology have been as important to car dealer profit margins as the DocuPad.

Illustration: Emmanuel Polnaco[br]Ever since Ford Motor Company began selling its Model T in 1908, few pieces of technology have been as important to car dealer profit margins as the DocuPad.

The 45-by-29-inch flat screen sits atop a salesman’s desk, giving him the ability to quickly coax customers through what would normally be mountains of paperwork. By enabling car buyers to check boxes with a stylus and sign contracts on the interactive screen, the DocuPad takes the friction out of a car salesman’s stock in trade—the upsell.

In a 2019 court deposition, the secretive Robert Brockman, 79, whose enterprise software company, Reynolds and Reynolds, sells DocuPad, offered a rare peek into the microeconomics of car sales. Brockman said the DocuPad enabled finance managers to upsell by at least $200 per transaction in a business where margins on every car sold or leased are typically razor-thin. “You recover the initial cost of DocuPad very, very quickly,” Brockman said, alluding to the $10,000 startup fee, plus an ongoing $1,000 monthly licence. “And then, from that point on, it is a massive generator of profits.”

Naturally, a dealer can get the DocuPad only if he’s also a licensee of one of Brockman’s integrated dealer management systems—digital platforms for everything from parts inventory and service scheduling to the machines that secure the thousands of keys at an average dealership. When you have thousands of captive dealers locked into multi-year contracts, those fees turn into $1 billion, with annual income estimated to be $300 million. And Brockman controls 98 percent of it through an offshore trust, a stake worth at least $3 billion.

Brockman’s ability to quietly pile up billions came to a crashing halt in October 2020, when he was charged with masterminding the largest tax-evasion case in American history, accused of hiding some $2 billion in income from the Internal Revenue Service (IRR) over the last two decades. Brockman has pleaded not guilty to all charges and is free on a $1 million bond. Neither Brockman nor his attorneys have responded to Forbes’s requests for interviews.

Brockman’s alleged scheme helped hide profits gushing from one of the nation’s most successful private equity (PE) firms, Austin, Texas–based Vista Equity Partners, founded by the nation’s richest Black person, Robert F Smith. Last October, Smith signed a non-prosecution agreement with the Department of Justice (DoJ) and confessed to what would have been a host of tax felonies tied to secret offshore accounts set up at Brockman’s behest. Starting in 2000, Brockman committed $1 billion in capital to Vista’s first fund and taught Smith the ins and outs of running an enterprise software business. He continues to hold large interests in several of Vista’s $73 billion in private equity funds. Smith has already paid a record $139 million to get the IRS off his back and agreed to cooperate with investigators in the case against his one-time benefactor and mentor.

The saga has all the drama and intrigue of a crime novel, involving a Playboy model, a network of offshore accounts and an encrypted email system in which Brockman referred to Smith as “Steelhead”. Brockman’s attorney, an Australian named Evatt Tamine, who functioned as the billionaire’s nominal trustee, was known as “Redfish”. The IRS was “the House” and Brockman, the tip of the pyramid, was “Permit”.

A months-long investigation by Forbes reveals that the alleged tax evasion is not the first, or only, sin Brockman may have committed during his impressive career. On his way to amassing a net worth estimated to be $6 billion, the Houston-based entrepreneur has left a trail of hundreds of arbitrations and lawsuits from auto dealers who are his core customers, claiming that his underhanded tactics cheated them, too, out of hundreds of millions.

*****

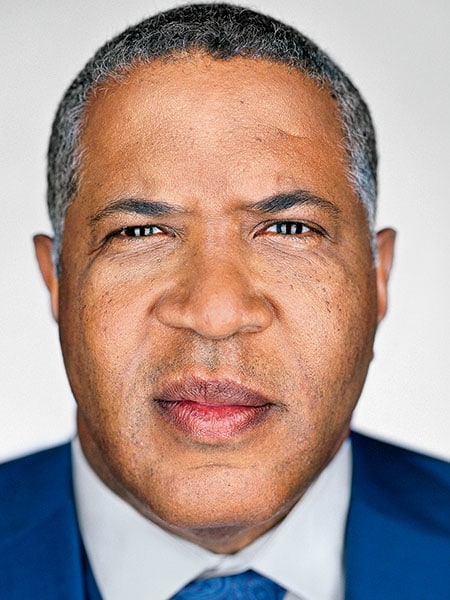

Born during the Second World War to a physiotherapist and a gas station owner, Robert Brockman grew up in St Petersburg, Florida, and graduated summa cum laude from the University of Florida in 1963, a member of its business honor society. While serving in the US Marine Reserves, he worked in marketing at Ford and then joined IBM in 1966, becoming a star selling mainframe computer services to auto dealers.  Faced with a billion-dollar take-it-or-leave-it scheme from Bob Brockman, financier Robert F Smith or ‘Steelhead’ took the bait

Faced with a billion-dollar take-it-or-leave-it scheme from Bob Brockman, financier Robert F Smith or ‘Steelhead’ took the bait

Image: Martin Schoeller for Forbes[br]In 1970 he left IBM, launched Universal Computer Services and taught himself how to program at a time when it involved feeding decks of punched cards into hulking machines. Soon he was providing dealers with printed weekly reports on parts inventory.

“Brockman was the first provider who could enable an owner to synthesise the financial statements of his 10 dealerships into one. He was doing this in the 1980s,” marvels Paul Gillrie, a veteran auto-industry consultant. By the late 1980s Brockman had dozens of computers installed at dealerships, and he introduced what remains one of his core software operating systems, called Power. On his personal website, since taken down, Brockman, who holds 21 patents, wrote: “I’m still a programmer at heart. And although I had to give up hands-on programming many years ago, I still stay very closely involved in all of our product decisions.”

By the early 1990s, Ford decided it didn’t want to be in the IT business, so it sold Dealer Computer Services to Brockman’s Universal Computer Services for $103 million. The deal came with a stipulation: Ford would allow Brockman to continue using the Ford blue oval, brand, letterhead, address and even the same employees for five years, incognito.

“When Brockman took over, it was like a frog in boiling water,” according to a consultant who advised dealers on arbitrations. “Ford was so laid-back and easygoing. The dealers trusted them, and Ford took very good care of them.” The dealers liked the tech upgrades—even the era’s clunky monitor beat the microfiche and paper volumes they were used to. “Brockman computerised it all, created a superior system.” And then, according to a typical case, he leveraged that goodwill by signing dealers to contract extensions “with the intention of locking in dealers beyond the life of their computer systems, in order to impose costly system upgrades”. Some dealers were irate when they realised that they hadn’t been dealing with Ford at all—and had little recourse against charges like $12,000 for the installation of a 500-megabyte hard drive or $2,400 for a printer.

Those who tried to get out of their contracts met the buzzsaw of Brockman’s litigation team. He had created what an industry insider refers to as “the Darth Vader contract” because it enabled his attorneys to destroy rebellious dealers. Many upgrades or new services came with lengthy contract extensions. Says Gillrie, “When you have a contract that gives you a monopoly on your customer for 30 years, you don’t have to listen to anything they say.”

In 2010, Jay Gill, a Fresno, California–based entrepreneur with 10 dealerships, was hit with a $3 million bill when he acquired Livermore Auto Group, which had been paying $35,000 a month to Brockman’s company. They settled for about half that. “Brockman made his money by screwing people,” Gill says. “Anytime you asked for something or you needed something, he would automatically extend your contract without you knowing. When you have a 12-inch-thick contract, it’s somewhere in there.”

Not even the threat of bankruptcy could free dealers from Brockman’s grip. When Orville Beckford, a Black dealer in Florida, was struggling despite a recapitalisation by Ford in 1994, Brockman went after Ford for the money and in a letter castigated it for backing what he asserted was an inept manager: “I would like to avoid this—however, short of paying ‘blackmail’ to this dealer, I see no other answer than to fight him legally to the end.” Beckford sued Brockman for defamation and won $250,000 in a jury trial.

Over the years more than 100 dealers, beaten in arbitration, refused to pay off their contracts with Brockman’s companies and wound up in federal courts. “Unfortunately, Ford created this monster,” Gill says. “I know unequivocally that I wouldn’t do business with this guy, even if it was free.”

*****

Dealmaker Robert Smith had no such reservations when he met Brockman in the late 1990s. Fresh out of Columbia Business School and a rising star in Goldman Sachs’ investment banking department, Smith was talking to Brockman about doing a buyout of his growing software business.

Brockman didn’t need financing from Goldman. His UCS had oodles of excess cash—which he apparently had no intention of sharing with Uncle Sam. According to the statement of facts signed by Smith in his non-prosecution deal, Brockman agreed to seed Smith with $1 billion in the 2000 creation of Vista Equity Partners—on the condition that Smith cooperate with him in creating what the DOJ’s indictment refers to as a “conspiracy and scheme and artifice to defraud”.

In 1997, Brockman, via his Bermuda-domiciled A Eugene Brockman Charitable Trust, set up a holding company in Nevis called Spanish Steps Holdings. Under Spanish Steps he created a British Virgin Islands company called Point Investments. This firm would act as Brockman’s straw buyer for investments in Vista. According to Smith’s statement, Brockman, in a “take it or leave it” proposal, insisted that Smith hold half his carried interest in the initial Vista Fund II via a “perfected foreign trust” like his own. Presumably, this way Brockman could take comfort in knowing they were in it together.

“I had one of those in-the-mirror moments,” Smith, 58, told Forbes in 2018, in a cover story, before any hint of criminality had emerged. “I looked at myself and asked, ‘If I don’t do this, how will I feel about it ten years from now?’ According to his statement, Smith had a relative of his then-wife, Suzanne McFayden, create a Belize-based trust called Excelsior, through which Smith funded his offshore investment company, Flash Holdings.

It’s legal for corporations to set up subsidiaries in tax havens to own patents and other high-margin intellectual property (IP)—software makers have long parked IP in Ireland, for instance. Likewise, hedge funds and private equity investors set up offshore trusts in which to direct proceeds of their carried interest. Such structures’ legality tends to be contingent upon how much control the ultimate beneficiaries have over the assets, and what they do with it.

Brockman could have gotten away with having his businesses held through the A Eugene Brockman Charitable Trust had he been able to show that he was a passive beneficiary—rather than the control freak that Smith alleges him to have been: “It became apparent to Smith that despite paperwork that indicated to the contrary, Individual A [Brockman] completely controlled Individual A’s foreign trust and related foreign companies, and made all substantive decisions regarding all of its transactions and investments.” Including, of course, the decision not to disclose any of it to the IRS. As Brockman said of himself in a 2019 deposition, “As you probably can tell, I’m into the details, big time.”In his statement, Smith explains that he was incentivised to deliver returns on Brockman’s $1 billion because Brockman had the power to replace him by forcing Vista to sell him their general-partnership control interests at Brockman’s price. Brockman controlled Smith with an iron grip the same way he did the car dealers.

With Brockman’s capital, Vista Fund II acquired the likes of SirsiDynix, Applied Systems, BigMachines, Brainware, Surgical Information Systems and SER Solutions. Brockman was intimately involved in directing the Vista team on how to apply his playbook of operating principles focussed on cost reduction and product consolidation. According to someone familiar with Vista’s early days, the budding private equity firm applied IBM’s process-oriented approach, learnt from Brockman, to acquire and grow software companies: “Everything that Vista knows about software came from Bob Brockman.”

One smart strategy employed by Vista has been software roll-ups. Take the case of former Vista portfolio company Ventyx—an Atlanta firm focussed on industrial management software. In 2005, Vista paid $70 million for MDSI, added Indus in 2007 for $240 million, then merged them into Ventyx. It then rolled in Global Energy Decisions and NewEnergy Associates and Tech-Assist in order to add key applications and market share. Then, in 2010, Vista sold Ventyx to Swiss power and automation giant ABB for $1 billion. Vista then distributed $799 million of the proceeds to an account at Swiss bank Mirabaud that was controlled by Brockman’s Point Investments.

Brockman also appeared to use Vista as a straw buyer to help him roll up other dealership software providers. In 2005, UCS acquired call-tracking and measurement company Callbright. The next year, Vista Fund II (all Brockman’s money) acquired Callbright’s competitor Who’s Calling—which it later sold to Brockman as well. According to Preqin, Smith’s first Vista fund, launched in 2000, went on to return more than 29 percent annually. If that return is to be believed, it would mean that Brockman and Smith multiplied the initial $1 billion more than tenfold.

*****

As Brockman was directing Vista’s growth from behind the scenes, his business was flourishing. In 2005, his software company reportedly had $530 million in revenue and $100 million in profits, with 2,600 employees. His computerised parts catalogue was installed in nearly 2,500 Ford and Lincoln-Mercury dealerships.

But Brockman was facing a big problem—Ford had developed its own electronic parts catalogue. In 2005, Ford refused to renew Brockman’s exclusive licence unless he agreed to a three-year wind-down of his existing contracts. Brockman sued, alleging violation of antitrust laws, but eventually dropped the suit.

His exclusive deal over, Brockman had to do something to replace the business. He then enlisted Smith to help with the deal of his career—a leveraged buyout of Ohio’s Reynolds and Reynolds in 2006 for $2.4 billion. Brockman put up $300 million in equity Vista added $50 million (of Brockman’s money). Deutsche Bank arranged the loans. The industry was shocked, assuming that much larger Reynolds would be buying UCS, not the other way around. Now Brockman had thousands of new clients to transition to his Darth Vader contract.

Almost immediately, there was a culture clash. A buttoned-up ex-Marine, Brockman was not well-liked at easygoing Reynolds. He prohibited employees from smoking, even during off hours, and reportedly monitored time spent on bathroom breaks. In a deposition, Brockman described his frustration with the company’s data security: “When I got to Reynolds, it’s kind of like I had been spending my life, you know, mopping and polishing the floor. And I inherited this house, and it has two inches of water on the floor.”

In 2008, during the Great Recession, Reynolds debt sold off in a flight to quality. Seeing his company’s loans trading as low as 35 cents on the dollar was too good for Brockman to pass up. Even though he had personally signed credit agreements barring him from buying any of Reynolds’s subordinated debt without the approval of first-lien holders, Brockman secretly bought about $20 million of Reynolds debt in 2009, according to an IRS investigation. To do so, Brockman, through his Aussie attorney Tamine, used funds held by Edge Capital Investments (like Point Investments, Edge was a Caribbean entity set up via a trust controlled by Brockman’s longtime CFO, Don Jones, “as a cover to shield Brockman’s ownership”, according to an IRS investigation). A year later, when Deutsche arranged a refinancing of Reynolds debt, Edge redeemed Brockman’s notes at par, netting $72 million on the trade and depositing the funds into an offshore account. According to the affidavit of an IRS investigator, “Tamine, at the direction of Brockman, then laundered approximately $57 million of the proceeds” through Brockman’s other accounts and companies, “including several of Vista Equity Partners’ funds”.

Some of the untaxed profits from Brockman’s lucrative trade allegedly went to fund his passions. His Frying Pan Canyon Ranch near Aspen, Colorado, was purchased for $15 million. He also directed his attorney to purchase a 209-foot luxury yacht named Albula, complete with a helipad, for $33 million. Brockman, an avid fisherman and hunter, was also fond of zipping by private jet to Córdoba, Argentina, for the hemisphere’s best dove shooting.

Smith was enjoying life too. In 2009, he relocated with Suzanne, his wife of 22 years, to Switzerland. The next year he redirected more than $30 million of his own untaxed capital gains into an account at Swiss Banque Bonhôte through which he bought two Alpine ski chalets in Megève, France. The family also maintained homes in Texas, California and Colorado.

Enter the 2010 Playboy Playmate of the Year, Hope Dworaczyk, with whom, his wife discovered, Smith was having an affair. This became an immediate concern for Brockman’s team. In August 2011, according to emails uncovered by Department of Justice investigators, Brockman’s CFO Jones, a.k.a. “King” wrote to trustee Tamine, a.k.a. “Redfish”: “Bob called concerned about the Robert Smith situation and what effect a nasty divorce might have on us. We agreed that if his business is dissected by her attorney, Point would be an initial target.” Indeed, in her divorce petition, Suzanne McFayden, who met Smith when they both attended Cornell in the 1980s, demanded full ownership of their homes, comprehensive support for their children, a prohibition against them ever associating with Dworaczyk and a “strict accounting of all monies expended” for Smith’s mistress’ benefit. And in what was perhaps her toughest ask, McFayden’s lawyers demanded that Smith get up to date with his taxes.

As Mr and Mrs Smith negotiated a divorce settlement, Brockman was looking for the exit.

In late 2012, he came close to striking a deal to sell Reynolds and Reynolds to KKR for $5 billion, but backed out. In 2013, Brockman attempted a dividend recapitalisation of Reynolds that would have valued the company at $5.3 billion and increased debt from $900 million to $4.3 billion. A Moody’s report at the time estimated Reynolds’s “free cash flow” that year at $350 million, with 40 percent margins. Brockman reportedly planned to take out $2.5 billion in cash. But this deal too fell apart. Bizarrely, after loans had been finalised and allocated to investors, all the trades were reportedly unwound and the issue withdrawn. Brockman then cancelled a well-publicised pledge of $250 million to Centre College in Danville, Kentucky, which he had attended before transferring to the University of Florida.

Vista was likewise feeling pressure. In a 2012 memo, Tamine told Brockman that he was beginning to encounter uncomfortable questions. “It is the involvement of Point Investments, an unknown non-US investor, which generally causes the compliance issues.” When “pressed on Point’s beneficial ownership,” Tamine wrote, “I have walked us through with minimal disclosure.”

At the end of 2013, Banque Bonhôte notified Smith that it intended to participate in the DOJ’s Swiss-bank programme and would be informing US authorities of his account. Realising the jig was up, Smith hurriedly filed an IRS application in March 2014, seeking inclusion in its amnesty programme for Americans who had failed to disclose their offshore accounts. A month later, his application was denied.

When Smith and McFayden finalised their divorce later in 2014, Brockman loaned Smith $75 million, according to court documents. That same year Vista wound down Brockman’s Fund II and exited its small stake in Reynolds and Reynolds.

Smith celebrated his newfound freedom in July 2015 by wedding Dworaczyk in a lavish, star-studded affair at Villa Cimbrone on Italy’s Amalfi Coast. Musicians Seal and John Legend performed.

Less than a year later, in June 2016, the alleged co-conspirators went into high gear in anticipation of a federal grand jury investigation. Tamine was dispatched to Oxford, Mississippi, to visit Don Jones’s widow, who was in possession of incriminating evidence, including floppy disks and hard drives. Said Tamine in an encrypted memo, “As you know, I even cut short the trip to Argentina to get back to Oxford to destroy more drives that had been discovered.”

By 2017, Tamine could see the writing on the wall. In a memo to Brockman he wrote: “Even if Robert Smith clears up his problems, the target is well fixed on me and we need to anticipate that we’ll be audited at some point.” In September 2018, agents in Bermuda raided Tamine’s home.

As the government closed in, Smith began upping his charitable giving. Around the time the IRS rejected his amnesty plea, Smith set up a foundation with hundreds of millions of dollars connected to the profits of Vista’s first fund. In 2016, he and his foundation pledged $50 million to Cornell University’s engineering school and $20 million to the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Most famously, Smith delivered a commencement speech at Morehouse College in May 2019, announcing that he would spend $34 million to pay off the student debt of the entire graduating class of the historically Black college.

Brockman, too, sought to burnish his philanthropic bona fides, donating $25 million to the Baylor College of Medicine and tens of millions more to erect buildings at Centre College and Rice University. Tamine, in a memo to Brockman, wrote of the importance of appearing charitable: “These activities would work as a strong barrier against an attack from the IRS.”

On October 15, 2020, US attorneys dropped their bombshell about Smith and Brockman. In exchange for an agreement not to prosecute, Smith would pay $56 million in taxes and penalties on unreported income plus another $82 million in penalties for concealing offshore accounts. Further, he would abandon his claims for $182 million in refunds derived from his philanthropic giving and earlier payments to Uncle Sam. “It is never too late to do the right thing,” said US attorney David Anderson. “Smith committed serious crimes, but he also agreed to cooperate”—against Brockman—which “has put him on a path away from indictment.”

Smith continues to preside over Vista, and only a handful of investors have shown signs of concern. New Mexico’s Educational Retirement Board has withdrawn a $100 million commitment, and the Virginia Retirement System, which has $350 million invested with Vista, says it is monitoring the situation. In late November 2020 Vista’s longtime president, Brian Sheth, announced he was leaving the company, implausibly telling Forbes it had nothing to do with Smith’s confessed transgressions: “I know for Robert and Vista the best is yet to come.” Vista now boasts $73 billion in assets under management.

In November, Brockman stepped down as CEO of Reynolds to prepare for his trial. So far, Bermudian and Swiss authorities have frozen his accounts, and Tamine is cooperating with the authorities. Brockman’s attorneys say he is suffering from early-stage dementia. So far his lawyers have persuaded the court to transfer the case from San Francisco to Houston in recognition of Brockman’s declining health.

Federal prosecutors dismiss Brockman’s symptoms as an “amorphous malaise” and point to his lucid deposition testimony from 2019, as well as a lengthy memo he sent to Reynolds’s vice chairman in May 2020 foreshadowing an all-too-familiar behind-the-scenes role he was planning: “My intent is to work 4 or 5 more years helping teach the next generation everything I know about how to run the company efficiently.”

â— With reporting by Antoine Gara

First Published: Apr 17, 2021, 08:21

Subscribe Now