He means he can use Chegg Study, the $14.95-a-month service he buys from Chegg, a tech company whose stock price has more than tripled during the pandemic. It takes him seconds to look up answers in Chegg’s database of 46 million textbook and exam problems and turn them in as his own. In other words, to cheat. (Matt asked that his real name be withheld.)

Chegg is based in Santa Clara, California, but the heart of its operation is in India, where it employs more than 70,000 experts with advanced math, science, technology and engineering degrees. The experts, who work freelance, are online 24/7, supplying step-by-step answers to questions posted by subscribers (sometimes answered in less than 15 minutes). Chegg offers other services students find useful, including tools to create bibliographies, solve math problems and improve writing. But the main revenue driver, and the reason students subscribe, is Chegg Study.

“If I don’t want to learn the material,” says a University of Florida sophomore majoring in finance, “I use Chegg to get the answers.”

“I use Chegg to blatantly cheat,” says a senior at the University of Portland. Forbes interviewed 52 students who use Chegg Study. Aside from the half-dozen students Chegg provided for Forbes to talk to, all but four admitted they use the site to cheat. They include undergrads and grad students at 19 colleges, including large and small state schools, and prestigious private universities like Columbia, Brown, Duke and NYU Abu Dhabi.

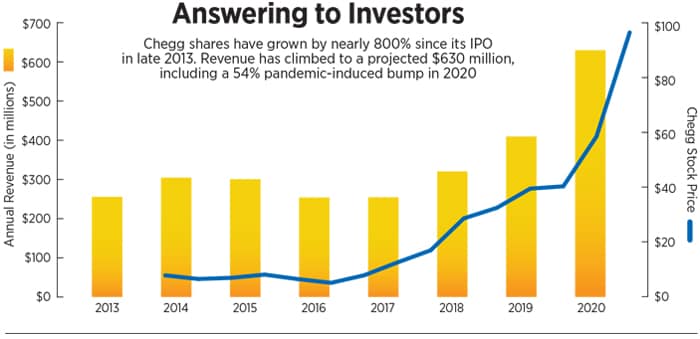

Subscriptions to Chegg have spiked since nearly every college in the world went virtual. In the third quarter of 2020, they grew 69 percent over the previous year, to 3.7 million. Nine-month revenue surged 54 percent to $440 million through September 2020 and is projected to hit $630 million for the year. Its market cap, meanwhile, has nearly quadrupled since March 18 last year, when the country began to lock down. Chegg is now valued at more than $12 billion.![dan rosensweig dan rosensweig]() Dan Rosensweig took over as CEO of Chegg in early 2010, but things have really accelerated during the pandemic. “The growth of the company is just extraordinary right now,” he said in late October 2020

Dan Rosensweig took over as CEO of Chegg in early 2010, but things have really accelerated during the pandemic. “The growth of the company is just extraordinary right now,” he said in late October 2020

Image: Getty Images[br]Chegg CEO Dan Rosensweig’s holdings of Chegg plus after-tax proceeds from stock sales add up to $300 million. Rosensweig, who declined to speak to Forbes, has said that Chegg Study was “not built” for cheating. He describes it instead as the equivalent of an asynchronous, always-on tutor, ready to help students with detailed answers to problems. In a 2019 interview, he said higher education needs to adjust to the on-demand economy. “I don’t know why you can’t binge-watch your education,” he said. “My view is education is going to have to come to us over the devices we have.”

Two Chegg executives, vice presidents Arnon Avitzur and Erik Manuevo, support Rosensweig’s claims about Chegg’s intent. “It’s there to offer students personalised service to help them get unstuck,” Avitzur says.

In a written statement, a Chegg president, Nathan Schultz, says: “We are not naive that [cheating] is a problem. And the mass move to remote learning has only increased it. We remain 100 percent committed to addressing it, and are investing considerable resources to do so. We cannot do it alone and are working with faculty and institutions, and will continue to do more, including educating students.”

Their investments don’t appear to be paying off. Undergrads in a finance course at Texas A&M last fall used Chegg to cheat on multiple online exams. Timothy Powers, who heads the university’s honor system office, says hundreds of students submitted answers they copied from Chegg more quickly than it would have taken them to read the questions.

“We’re trying to stop academic misconduct, and students are convincing themselves that all their peers are doing this,” Powers says.

![cheat for profit cheat for profit]()

Throughout the pandemic, schools have spent millions on remote proctoring, a controversial practice in which colleges pay private companies like Honorlock and Examity to surveil students while they take tests. The proctoring outfits lock students’ web browsers and watch them through their laptop cameras. Critics say the services invade students’ privacy.

Although most students Forbes interviewed say remote proctors make them too scared to cheat on exams, several note that they chegg their online exams regardless of whether they’re proctored. “As long as you’re not using the school’s Wifi, you won’t get caught,” says a sophomore at a large state school.

*****

Students have always cheated. In the 12th century, Chinese test takers sewed matchbox-sized copies of Confucian texts into their clothes so they could cheat on civil service exams. Henry Ford II dropped out of Yale in 1940 after he was exposed paying someone to write his senior thesis.

The size of the problem is difficult to measure, says Penn State professor Linda Treviño, co-author of the 2012 book Cheating in College. Part of the challenge is defining what constitutes cheating. Is it getting an answer to a homework problem from a friend, peeking at a classmate’s paper during an exam, paying someone to take a test for you, plugging in answers from Chegg? It’s also tough to get reliable information. “You’re depending on people who cheat to be honest with you about whether they cheated,” Treviño says. Her book pegs the share of college students who cheat at roughly two-thirds.

Students cheat for several reasons. To get better grades so they can get into an elite law or medical school. To pass required distribution courses (engineers forced to study Shakespeare and vice-versa) that they don’t care about. To save time so they can play varsity football or work a job that pays for school and supports loved ones. And because they feel that everyone else does it, and they don’t want to be at a disadvantage if they don’t cheat too.

They don’t worry about getting caught. Even more troubling, they either don’t think they’re doing anything wrong or they don’t care.

A 2020 George Washington University graduate who is applying to grad school says she tried to use Chegg the way company executives say it was intended, “more as an instructional tool.” But her mechanical physics course was very tough, and she chegged her physics homework at the last minute. Chegg Study started life as Cramster, a Southern California startup founded in 2002 by a recent UCLA engineering grad, Aaron Hawkey, then 24. In college, Hawkey wished he had a place to look up answers to tough problems. His idea: Build a website that had carefully outlined solutions to math, science and engineering problems.

He and his partner Robert Angarita, then a 23-year-old undergrad at the University of Southern California, knew they needed to generate a lot of high-quality answers. One of Angarita’s professors had a cousin in India and encouraged them to recruit well-educated freelancers there who would respond to questions students uploaded. In late 2010, Chegg acquired Cramster for an undisclosed sum.

Chegg had launched just two years before Cramster, in 2000, as CheggPost, an online campus flea market founded by University of Iowa sophomore Josh Carlson, who combined “chicken” and “egg” to make the name. After teaming up with an ambitious Iowa State MBA student from India, Aayush Phumbhra, he bowed out in 2005. Phumbhra and new partner Osman Rashid shortened the name to Chegg and switched their strategy to textbook rentals.

Students were happy to pay $30 to rent a $250 textbook for a semester. But book purchases, warehousing and shipping bled cash. Venture capitalists invested $280 million anyway, and by 2010, lead investor Ted Schlein, a partner at Silicon Valley powerhouse Kleiner Perkins, recruited Dan Rosensweig to turn Chegg around.

Rosensweig, now 59, had proven leadership chops, first at New York publisher Ziff Davis, where he ran a Ziff spinoff, tech news site ZDNet, in the late 1990s. After serving as Yahoo’s COO from 2002 to 2007, Rosensweig worked briefly in private equity and then as CEO of Guitar Hero.

Though none of his pre-Chegg experience touched on education or textbooks, Rosensweig likes to say he was attracted to Chegg because his mother taught public school while he was growing up in Scarsdale, New York, and he had two daughters who were getting ready for college. As soon as he started at Chegg in early 2010, he added a tagline to his email signature that read, “We put students first.” “I thought it was a little cheesy,” says Chi-Hua Chien, then a Kleiner Perkins partner, “but Dan had a vision to turn Chegg into a complete end-to-end platform for learning.”

In November 2013, with a balance sheet in the red and competition from Amazon, which had started renting textbooks in 2012, Rosensweig took the company public. The stock sunk from an initial $12.50 to a low of $4 in early 2016. In early 2015, book distributor Ingram agreed to buy and distribute Chegg’s inventory while Chegg continued as the marketer for textbook rentals under the Chegg brand (in 2019 Chegg switched distributors to FedEx). Rosensweig acquired more than a dozen companies he thought would fit his plan to offer services students needed, including Internships.com and Study Blue, which helps students make online flashcards. But most such companies haven’t produced much revenue and some simply failed, including Campus Special, a daily deals site for students that Chegg bought for $17 million in April 2014 and shut down the same year.

Fortunately for Rosensweig, Chegg Study was enjoying steady growth and little competition. Its only serious rival, privately held Course Hero, is a much smaller operation, valued at $1.1 billion, that generates most of its answers from students.

*****

In mid-January, Chegg issued a press release about a new program called Honor Shield. It enables professors and instructors to pre-submit exam or test questions, “preventing them from being answered on the Chegg platform during a time-specified exam period”. Eleven months after colleges switched to remote learning, it quotes Chegg president Schultz as saying that because of the “sudden impact” of the pandemic, “a small number of students have misused our platform in ways it wasn’t designed for.”

It’s doubtful that Honor Shield will dent students’ chegging. At UCLA, physics lecturer Joshua Samani says that he believes “an astonishingly large portion” of his students have used Chegg to cheat on his exams and quizzes. But he doesn’t try to catch them. “If you’re spending your time attempting to battle Chegg, you’re going to lose,” he says.

At the end of the 2020 spring term, North Carolina State University lecturer Tyler Johnson caught 200 students who had used Chegg to cheat on the final exam in his intro to statistics course. Johnson says, “It’s just unconscionable. Chegg absolutely knows what students are doing.”

It’s unreasonable to lay all the blame for cheating at the feet of Chegg, of course. Human nature is at fault, especially when studying from home makes it much harder to get caught. But Chegg has weaponised the temptation and is cashing in on students’ worst instincts. Our arsenal of digital tools and global connectivity should be deployed to transform education for the better. Instead, Chegg is using them to outsource cheating to India. That is a tragedy.

â— With reporting by Christian Kreznar

Illustration: Matt Chase[br] It’s called “chegging.” College students everywhere know what it means. “If I run out of time or I’m having problems on homework or an online quiz,” says Matt, a 19-year-old sophomore at Arizona State, “I can chegg it.”

Illustration: Matt Chase[br] It’s called “chegging.” College students everywhere know what it means. “If I run out of time or I’m having problems on homework or an online quiz,” says Matt, a 19-year-old sophomore at Arizona State, “I can chegg it.” Dan Rosensweig took over as CEO of Chegg in early 2010, but things have really accelerated during the pandemic. “The growth of the company is just extraordinary right now,” he said in late October 2020

Dan Rosensweig took over as CEO of Chegg in early 2010, but things have really accelerated during the pandemic. “The growth of the company is just extraordinary right now,” he said in late October 2020