Not for Dr Phillip Frost. As we drive to his office in his white, 7 series BMW, Miami’s second-richest man and a 50-year resident can’t help but lecture me on more than a dozen varieties of palms sprouting like weeds from the lapses in pavement.

“See the fruit on that one hanging? It’s yellow. That’s a lady palm. Beautiful, isn’t it? And that’s a date palm in front. This is a Chinese fan palm—forms a fan like the elephant ear—and that is a sabal palm, flowering. Isn’t that pretty?” Then Frost decides to test my retention. “And those crooked ones are what?” After a few seconds he answers his own question. “Coconut palms. Remember I told you coconut palms grow crooked? Royals tend to grow up—these are royals.”

In this sweltering city of conspicuous consumption, where nearly everyone drives with windows rolled up and the air-conditioning and radio blasting, Frost, with his botanical obsession and insatiable appetite for learning, is an anomaly. He is a businessman and an investor, but he is also a scholar, inventor and fervent patron of the arts and sciences. And anyone spending time with the self-effacing octogenarian will readily testify that it is precisely his meticulous attention to seemingly mundane details—like those many varieties of palm trees—that underlies his uncanny ability to spot and capitalise on opportunities.

Frost is a board-certified dermatologist and irrepressible entrepreneur who is also the chairman and CEO of Opko Health, a midsize pharmaceutical and medical-diagnostics company with promising remedies in numerous areas, including chronic kidney disease and prostate-cancer detection. Though his company has revenues of $1.2 billion and will lose about $50 million in 2016, he insists Opko will mean more to medicine than any of his previous endeavors, including drug-industry pioneers like Key Pharmaceuticals, Ivax and Teva Pharmaceuticals. It’s a bold statement from a man who played a major role in creating the modern generic-pharmaceutical business and—given that shares in Opko are down 39 percent in the last 18 months—more than a little self-interested.

“What we are building here is a company that will have half a dozen products, each capable of doing more than a billion dollars in sales and some several billion,” he says, pointing to a printout displaying overlapping circles that highlight five core Opko markets: Urology, nephrology, genetics, bio-reference and aging/metabolic syndrome. “In the case of human growth hormone, where we are partnered with Pfizer, that is a $3.5 billion market.”

Unlike most of his pharma peers, Frost has the mind-set of a savvy value investor, only it’s enhanced by a deep understanding of molecular biology and a penchant for swiftly striking opportunistic deals. His office desk is stacked with pitchbooks and proposals, as well as dual flat-panel Bloomberg screens, with dozens of stocks on his watch list blinking green and red. “Phil has an incredible vision of where to position himself within health care,” says Oracle Partners’ Larry Feinberg, a veteran hedge fund manager who has owned shares in Frost companies since the 1990s. “He views Opko as his holding company. It is his Berkshire Hathaway of health care.”

![mg_93705_frost_280x210.jpg mg_93705_frost_280x210.jpg]()

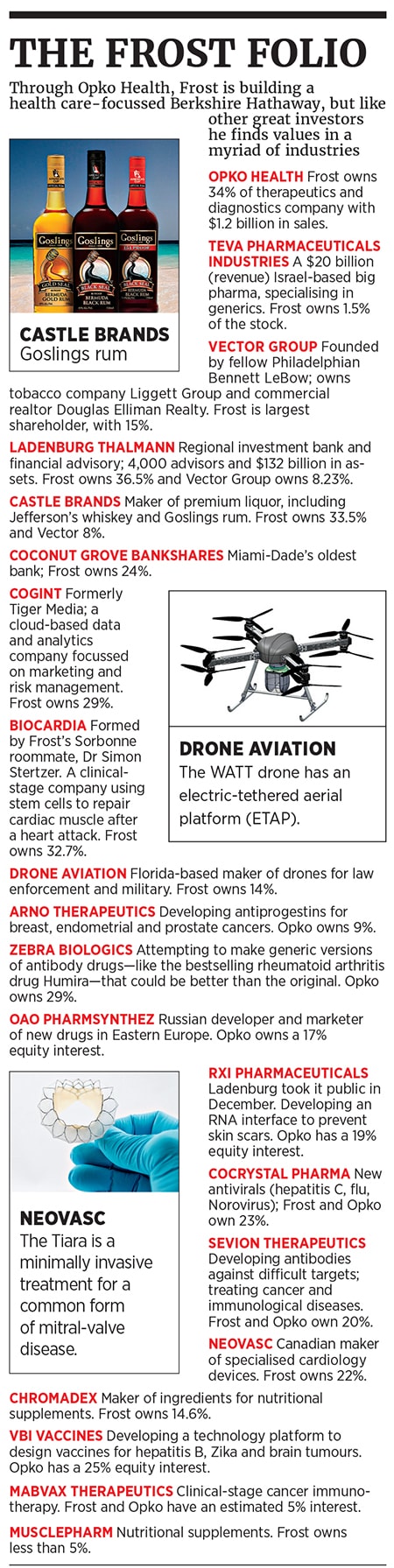

Through Opko and other entities, Frost has strayed far from health care. He has big stakes in dozens of public and private companies, ranging from Vector Group, owner of tobacco company Liggett and commercial real estate broker Douglas Elliman, to Castle Brands premium spirits and investment firm Ladenburg Thalmann & Co. He has invested in a slew of promising startups, such as a data-fusion company, a drone surveillance provider and BioCardia, a biotech developed by his college roommate, renowned Stanford Medical School cardiologist Simon Stertzer, which is trying to find a way to use stem cells to rejuvenate hearts damaged by heart attack.

Tireless at age 80, Frost is working on his fifth billion in net worth, but he is giving it away nearly as fast as he is making it. The Frosts have no children, but he and his wife, Patricia, through their hands-on approach to philanthropy and hundreds of millions in funding, are on a mission to transform Miami from a city best known for its beaches, golf courses and trendy Latin-Caribbean cuisine into a mecca for art and serious science.

Frost’s Horatio Alger story contains a healthy dose of serendipity. He was born in 1936, in the midst of the Great Depression, the third son of a shoe-store owner from South Philadelphia. A stellar student from the start, he attended Philadelphia’s selective Central High School and the University of Pennsylvania, majoring in French literature. After his junior year in Paris studying at the Sorbonne, he had a chance meeting with a former schoolmate at Penn’s cafeteria, alerting him to a scholarship that was being offered to a new medical college in New York City called Albert Einstein and available to graduates of his high school. Frost applied and won a full scholarship. Einstein quickly established a reputation as one of the top med schools in the country.

His decision to specialise in dermatology also contained an element of chance. As an undergrad he developed an unsightly wart on his elbow that prompted him to go to a Penn faculty member who happened to be doing research on cantharidin, otherwise known as Spanish fly, for an application to remove warts.

“I was interested in a specialty that would permit me the time to reflect and do [other] work. I knew that surgery could never be for me because you’re tied up in operating rooms most of the time. And I needed the freedom to do things,” Frost says. Fortuitously, the professor who cured his wart later offered him a postgraduate residency in dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania.

After his residency and two years as a lieutenant commander in the US Public Health Service at the National Institutes of Health, Frost landed a spot on the faculty of the University of Miami’s dermatology department in 1966. Seeing patients and teaching med school weren’t enough to satisfy his insatiable curiosity, so at night he invented a disposable tool for taking skin biopsies (still used today). During negotiations to sell his invention to Miles Laboratories in 1969, Frost met a young lawyer with a silver tongue named Michael Jaharis.

Frost’s friendship with Jaharis blossomed into a business partnership after the lawyer decided to quit his corporate job to help Frost build a business around a novel ultrasound device used to clean teeth that Frost had purchased. He had a thriving dermatology practice, with patients that included Jackie Gleason, who once filled Frost’s mother’s hospital room with roses after he discovered they were convalescing in the same hospital. By 1972 he had become the chairman of dermatology at Miami’s Mount Sinai Medical Center.

That same year, another chance meeting: At Miami’s airport, while waiting to board a plane to New York, Frost ran into a high school classmate who was a top executive at Key Pharmaceuticals, then a struggling drugmaker focussed on cold remedies. “By the time we got to New York, we agreed to put our little company, which had some cash and some inventions, together with Key, which was public,” Frost says in his apartment in New York’s Pierre hotel, overlooking Central Park. “They had great technology, but they didn’t have the people to recognise what they had. They had the first controlled-release technology for drugs.”

Key Pharmaceuticals was Frost and Jaharis’ ticket to serious wealth. After reformulating its main asthma drug, which had initially been combined with a cough suppressant, into an asthma-only remedy with a controlled release, Key’s Theo-Dur became the nation’s best seller. Key followed up with the first nitroglycerin slow-release patch remedy (Nitro-Dur), used to treat heart disease, also a big hit. Ultimately Schering-Plough purchased Key Pharmaceuticals in 1986 for $836 million. By then Jaharis and Frost were on The Forbes 400. Frost, age 50, had a net worth of at least $150 million ($330 million in current dollars) and was Schering’s largest individual shareholder.

But instead of retiring to collect dividends, Frost blazed a trail in the nascent generic-drug business with another company he formed, called Ivax. In the early 1990s, when the low-margin generic-drug business was getting bad press for products of questionable quality, Frost presciently bought up companies and expanded internationally. Again he used connections to get an edge. In 1994, for example, Frost bought one of the Czech Republic’s largest pharmaceutical companies, known as Glaena.

“I had heard that an important Czech pharmaceutical company was being privatised by the government,” Frost says. “One of my friends from Colombia, South America, had an apartment in Miami, and he had a Czech friend in Toronto.” So Frost made some calls and found out that Novartis and two other European companies were interested in bidding, but Frost’s Miami-Toronto connection was able to arrange a last-minute meeting with Vaclav Havel, then the president of the Czech Republic. “I told him, ‘Look, if you do a deal with us, we’ll guarantee you’ll keep at least 900 of the 1,200 employees,’” says Frost, who shrewdly noticed that the politician’s primary goal was saving jobs, not getting top dollar for the assets. The Czech deal, which cost Ivax only $50 million, included prime real estate, subsidiaries in all the former Soviet Republics and $20 million in the bank.

“Phil turned Ivax from a domestic drug company to a global generics-pharmaceutical company,” Feinberg says. “It wasn’t subject to just the vagaries of the US [market]. It really had strong positions in both generic and proprietary pharmaceuticals throughout the entire world. It became a very valuable asset.”

In 2005 Israel’s Teva Pharmaceuticals paid $7.6 billion for Ivax, making Frost a billionaire. For the first time.

Command central for Frost’s empire is a shimmering 15-storey glass-and-steel building he owns at 4400 Biscayne Boulevard in downtown Miami. Lining the walls of the 15th-floor executive suite, below an electronic ticker tracking Frost stocks, are beautifully framed photographs of Art Deco Miami Beach circa World War II from negatives Frost rescued when the city’s Bayfront Park library was being demolished in the mid-1980s. Just outside Frost’s office is a glass-enclosed “atrium”, where he lunches daily with senior executives, including Dr Jane Hsiao, a brilliant chemist with an MBA, whose late husband, Charles, co-founded Ivax with Frost. Hsiao is a vice chairman of Opko and ranks 46th on the Forbes list of Self-Made Women, with a net worth of $320 million. Another regular lunch mate is Steven Rubin, a former mergers-and-acquisitions lawyer who joined Frost in 1986 after Frost sold Key and started Ivax. Rubin is Frost’s deals guy, sitting on the boards of many of his companies. A newcomer to the inner circle is CFO Adam Logal, Opko’s accountant and Frost’s liaison to Wall Street. The conversation is almost always about deals, which flow into Frost headquarters on a daily basis. Often company executives and others are invited to make presentations.

“Phil is a face guy,” Rubin says. “He doesn’t do [meetings] over the phone. He’ll be like, ‘I just read you have an idea. Why don’t you come down on Friday and see me?’ I think that’s part of his calculus to get a gut feeling about people.”

One of Frost’s CEOs is Richard Lampen, an ex-banker who worked for Salomon Brothers in the go-go ’80s and now runs regional broker Ladenburg Thalmann on the 12th floor.

In the aftermath of the dot-com bubble in 2001, Frost bought into Ladenburg, then a tired 120-year-old investment bank known mostly for risky small-cap IPOs and cold-calling brokers. Frost has since financed its impressive recent growth. In the last 10 years revenues have climbed from $30 million to $1.1 billion, and a series of regional brokerage acquisitions has swelled the firm to 4,000 financial advisors with client assets of $130 billion.

“Thanks to Phil, we punch way above our weight,” Lampen says.

One executive who spends a lot of time at Frost’s staff luncheons these days is Dr Charles Bishop, the man in charge of Rayaldee, a newly approved drug that boosts vitamin D, which Opko is aiming squarely at a segment of the $12 billion market for treating chronic kidney disease. Opko acquired Bishop’s startup in 2013. Frost had heard about the promising remedy during a casual lunch with a Toronto pharma exec. Hours later Bishop had a voice mail from Frost.

“I returned the call immediately,” Bishop recalls. “He says to me, in classic Phil fashion, ‘Can you get to Miami in three hours?’”![mg_93703_museum_of_science_280x210.jpg mg_93703_museum_of_science_280x210.jpg]() The Frosts are on a mission to make Miami a science mecca. Their new Museum of Science will feature a 500,000-gallon aquarium and a planetarium

The Frosts are on a mission to make Miami a science mecca. Their new Museum of Science will feature a 500,000-gallon aquarium and a planetarium

Given that it was nearly Thanksgiving, Bishop persuaded Frost to wait a few days. “We had prepared to give him a full presentation... I came with my slide deck. We got through four slides and Phil says, ‘That’s enough of the slide presentation. Can we talk about a deal?’”

That sort of impatience is a Frost deal-making hallmark. He had done his homework and had decided that kidney disease was going to be a big business for Opko. Chronic kidney disease afflicts some 25 million people in the United States, including 9 million or so in stages 3 and 4. Opko’s Rayaldee, which analysts forecast could surpass $500 million in sales in the US alone, has the first product approved by the FDA to correct vitamin-D insufficiency through a one-a-day capsule with an extended-release formulation.

Not all of Frost’s deals have been warmly received on Wall Street. In 2015 Frost announced he would pay $1.47 billion for Bio-Reference Labs, one of the largest full-service clinical laboratories in the US, known for its expertise in genomics and genetic sequencing. Opko’s stock plummeted by more than 50 percent within four months of the announcement and has begun to recover, by about 20 percent, only in the last few months, with Rayaldee’s launch.

One promising Opko diagnostic that will leverage Bio-Reference’s network and marketing is Opko’s new 4Kscore blood test, which accurately assesses the risk of prostate cancer for men with elevated PSA (prostate-specific antigen) readings. Frost says, “If you have an elevated PSA, the tendency was to be biopsied, a painful procedure associated with infection and bleeding. And of the biopsy results, maybe 60 percent turn out to be negative.” He notes that there are an estimated 30 million PSA tests per year in US, and perhaps 25 percent of the results are elevated. Opko’s 4Kscore test costs $1,900.

“I wasn’t a big fan of his purchase of Bio-Reference labs,” money manager Feinberg admits. “But people always doubt Phil because they don’t understand what he is doing. They short his stock, but eventually he makes it work. He doesn’t give up. He has the tenacity and capital.”

David Gibbes Miller, 23, has never met Phillip or Patricia Frost, but the couple have opened doors for him that he never could have imagined. A Tallahassee native, Miller was an Eagle Scout and straight-A student in high school, but his family couldn’t afford to send him to a prestigious private college without significant debt, so he took the scholarships he was offered to Florida State University, where he majored in religion with a pre-med focus. At FSU Miller excelled, graduating summa cum laude in 2015. During his senior year he organised and hosted an undergraduate conference on bioethics at Florida State.

Upon graduation Miller was awarded Frost’s version of the Rhodes Scholarship. The programme, called Frost Scholars, sends 10 public-university students from Florida and four from Israel to Oxford each year to conduct research and earn a master’s degree in a STEM discipline.

At Oxford Miller studied medical anthropology with an interest in epidemiology and public health, completing a dissertation in the process. Another Frost Scholar in his cohort was Kaitlin Deutsch, 23, a graduate of the University of South Florida. Deutsch was recently awarded an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship and is at Cornell getting her PhD in entomology, studying native bees in an effort to boost their ability to pollinate plants. During her year at Oxford, where she earned a master’s in biodiversity, conservation and management, she made an important discovery soon to be submitted to a science journal: The so-called deformed-wing virus, a scourge decimating honey bee colonies, may have jumped species to another pollinator insect, the hoverfly.

“The [Frost] scholarship set me up in a way that allows me to shoot much higher,” says Miller, who is now a predoctoral fellow at the NIH and will soon apply to top medical schools.

Ultimately Miller and Deutsch both hope to return to Florida. Nothing could make the Frosts happier. “We are hoping that everyone is going to come back that graduated from Florida,” says Patricia, a former teacher and current member of the board of governors of Florida’s State University System.

“We want to make Miami more of a technological and science centre. When we came here, people thought of Miami as anything but that,” Phillip says, noting that the couple’s recent $100 million gift to the University of Miami was made with this in mind. “We feel that it begins with education. We need to start at the top with the universities and even the graduate students. The fastest way to achieve this is to attract a cadre of top-notch scientists, starting with chemistry and molecular biology.”

According to him, part of that $100 million will go toward developing an institute of chemistry and related sciences. “There will be a new building and new professors,” he says. “We hope all this will encourage new startups.”

The Frosts have signed Warren Buffett and Bill Gates’ Giving Pledge, but they are the opposite of so-called “chequebook philanthropists”. In fact, they are so hands-on that they have generally refused to hire consultants even for their world-class art collection, which has included American Abstract Expressionists, French Impressionists and old masters like the Flemish painter Jean-Baptist de Saive. The couple have endowed the University of Miami’s School of Music and Florida International’s Art Museum, and Patricia is regularly in touch with their directors, even helping select architects for small remodeling jobs.

“We are involved to the nth degree at the new science museum,” she says, referring to the $45 million of the Frost’s generosity that has gone into the construction of Miami’s new 250,000-square foot Patricia & Phillip Frost Museum of Science. After significant delays, the new facility, which has a planetarium and a massive multilevel marine aquarium, will open in March 2017.

In the elegant breakfast room of the Frosts’ grand Venetian palazzo built on Miami’s exclusive Star Island using imported Italian limestone, Patricia serves homegrown tropical fruits, all freshly picked from their expansive gardens and greenhouse, which include more than 150 varieties of palms that Phillip tends to. “The museum will try to emphasise basic science as illustrated by what is happening in this microclimate,” he says. “We want the young people to have an experience so that when they walk in they are awestruck. Then, as they spend more time there, it inspires them to work in the sciences.”

The Frosts are on a mission to make Miami a science mecca. Their new Museum of Science will feature a 500,000-gallon aquarium and a planetarium

The Frosts are on a mission to make Miami a science mecca. Their new Museum of Science will feature a 500,000-gallon aquarium and a planetarium