Yuan’s son, a college freshman, has become an emergency Zoom user, too. “I told my son, ‘I finally realised why I was working so hard,’” Yuan says. “I realised, ‘Maybe I built these tools just for you to use in your online class now’.” This newfound respect still wasn’t enough to stop either kid from battling for the family’s Wi-Fi with dad, jokes Yuan, 50.

Welcome to the new work-from-home family life: Conducted, increasingly, over Zoom. As the coronavirus ravages the planet, leading to quarantined cities, states sheltering in place and schools and universities closing down worldwide, Zoom has emerged as one of the leading tools to keep businesses up and running, students learning and people connected through virtual birthday parties, happy hours and yoga classes.

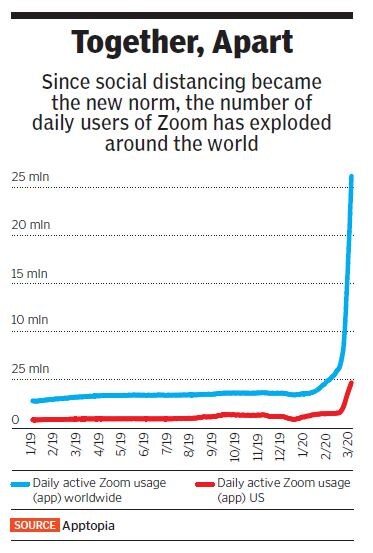

On the last Saturday of March, nearly 3 million people globally downloaded the Zoom app on their mobile devices for the first time—a record for the company, bringing the number of downloads since its April 2019 IPO to more than 59 million, according to mobile intelligence firm Apptopia. Zoom recently ranked No 1 among all free apps on Apple’s App Store, ahead of Google, WhatsApp and even Gen Z favourite TikTok. None of that accounts for the millions who tune in via laptop or desktop computer.

All of this has pushed Zoom, based in San Jose, California, into a new financial stratosphere. Its shares are up by 143 percent since the IPO and 44 percent in the last month—a time when the S&P 500 fell by 11 percent—giving the company a market cap of $42 billion and Yuan a net worth of $5.5 billion, making him one of the richest self-made newcomers on this year’s Forbes Billionaires list. Even before the spread of Covid-19, Zoom was on a tear, with at least 81,000 paying customers, including Samsung and Walmart. It posted revenues of $623 million and net profits of $25 million through its fiscal year ending January 2020, up by 88 percent and 234 percent, respectively.![zoom zoom]() Zoom’s Latin America team enjoys a virtual happy hour[br]Zoom isn’t just a darling of Wall Street. It’s a social media phenomenon. On Twitter, TikTok and elsewhere, Zoom has gone viral—quite a feat for a piece of business software. “Just got an email from a prof: ‘As a reminder, you are required to wear clothes during Zoom meetings’. Rules are made when they become necessary, not before,” one Twitter user quipped, getting more than 85,000 likes. Joked another, to 21,000 likes: “Lol you thought you were better than me cause you went to Harvard??? We’re all attending Zoom University now.” (The real Harvard is conducting all of its remaining classes on, what else, Zoom.)

Zoom’s Latin America team enjoys a virtual happy hour[br]Zoom isn’t just a darling of Wall Street. It’s a social media phenomenon. On Twitter, TikTok and elsewhere, Zoom has gone viral—quite a feat for a piece of business software. “Just got an email from a prof: ‘As a reminder, you are required to wear clothes during Zoom meetings’. Rules are made when they become necessary, not before,” one Twitter user quipped, getting more than 85,000 likes. Joked another, to 21,000 likes: “Lol you thought you were better than me cause you went to Harvard??? We’re all attending Zoom University now.” (The real Harvard is conducting all of its remaining classes on, what else, Zoom.)

Much of the Zoom boom is fuelled by Yuan’s decision to provide unlimited free access—first to affected regions in China and then, in mid-March, to all schools shut down in the United States, Italy and Japan. He’s since expanded the offer to schools in at least 19 other countries around 84,000 have signed up. Add to that millions of new individual users taking advantage of Zoom’s complimentary 40-minute video chats (available to any individual or group with fewer than 100 participants), which were already free before the pandemic. Zoom won’t say how much money all this free service is costing, but Stifel analyst Tom Roderick estimates the additional tab at $30 million to $50 million. And all those people are sucking up costly bandwidth—meaning Zoom is likely having to invest in public cloud resources as a stopgap, estimates Sterling Auty, an analyst at JPMorgan Equity Research. Zoom says its infrastructure can already support 8 billion meeting minutes per month: “In the case of an unprecedented, massive influx of demand, we have the ability to access and deploy tens of thousands of servers within hours.”![online classes online classes]() Kindergarten teacher James Baldwin reads a children’s book to his students (next page) from his home in Brookline, Massachusetts, a Boston suburb

Kindergarten teacher James Baldwin reads a children’s book to his students (next page) from his home in Brookline, Massachusetts, a Boston suburb

Jessica Rinaldi / The Boston Globe Via Getty Images[br]While Yuan’s generosity might be expensive in the short term, it will undoubtedly pay off richly for Zoom, which is already well on its way to becoming the generic term for videoconferencing, much as the brand names Xerox, Kleenex and Google are for their products. (According to its S-1, the majority of its top customers in 2018 had started out with a free account.) Zoom’s biggest challenge now is not how to make money but ensuring that its systems don’t crash under the weight of millions of new users or collapse under the spotlight.

“It was not a hard decision,” Yuan says. “When we thought about this decision, we were very excited. We know that whatever problems we face, we will overcome. Cost, our public company gross margin, our capacity: Everything else is secondary.”

The son of mining engineers in China’s eastern Shandong Province, Yuan grew up fascinated by entrepreneurs like Bill Gates. After graduating from Shandong University Science & Technology with a degree in applied mathematics in 1991, he decided to head to America. Before his departure, US Customs asked for an English-language version of his business card. It listed Yuan as a consultant, and he was misunderstood to be a part-time contractor. His visa was denied. For the next year and a half, the now-sceptical immigration services would deny him seven more times. But Yuan refused to give up.

He eventually made it to California and got a job at Webex, an early player in web-conferencing and videoconferencing applications. It was acquired by Cisco in 2007, and Yuan left four years and four months later, disillusioned by the quality of the service. He started to build Zoom and began offering to hook up some in-need organisations and institutions, such as the University of San Francisco, for free.![virtual meeting virtual meeting]() Jessica Rinaldi / The Boston Globe via Getty Images[br]Now that altruistic impulse is taking on global importance as Zoom has become vital for the work-from-home economy. But it’s far from the only company stepping up to meet this trend—and standing to profit later. Google and Microsoft also announced they were opening up more free features for their own classroom and videoconferencing tools. RingCentral, a Belmont, California–based cloud communications company, and Newsela, a New York City–based ed-tech firm, are two of a host of lesser-known players doing the same.

Jessica Rinaldi / The Boston Globe via Getty Images[br]Now that altruistic impulse is taking on global importance as Zoom has become vital for the work-from-home economy. But it’s far from the only company stepping up to meet this trend—and standing to profit later. Google and Microsoft also announced they were opening up more free features for their own classroom and videoconferencing tools. RingCentral, a Belmont, California–based cloud communications company, and Newsela, a New York City–based ed-tech firm, are two of a host of lesser-known players doing the same.

But likely no other company has signed up so many new users, so fast. How can Zoom possibly keep up? “Is your platform prepared for practically every college class in America to be using it? Simultaneously? Asking for a whole lot of friends,” said Adrienne Keene, an assistant professor of American studies at Brown University, via Twitter. “It’s unrealistic to expect we can just transfer class to a Zoom call and things will be fine,” she later emails Forbes, noting that some students live internationally, have spotty Wi-Fi or have no quiet space at home. “However, I am looking forward to seeing their faces and hearing their voices.” Yuan is not worried. He’s confident in Zoom’s infrastructure, and his team is working on other work-from-home- and study-from-home-inspired features, from better face lighting to a lecture tool for professors, while he continues to roll out Zoom to as many affected schools as his team can handle. “I feel like overnight, this is one of the catalysts where in every country, everybody’s realised they needed to have a tool like Zoom to connect their people,” Yuan says. “I think from that perspective, we feel very proud. We’ve seen that what we are doing here, we can contribute a bit to the world.”

Yuan may not have predicted all the ways Zoom would facilitate a social-distancing lifestyle. But the company started to brace itself for huge changes when Covid-19 first disrupted business in China beginning in January. At that time, customers such as Walmart and Dell reached out with concerns, Yuan says, wondering if their local employees would be able to move full-time to communications through Zoom. In the run-up to going public, Zoom had trained its staff on responses to natural disasters, though the company didn’t anticipate that the disaster en route would be a pandemic.

![zoom app zoom app]()

Zoom’s 17 data centres were designed to handle traffic surges of up to 100x, Yuan says. “The beautiful part of the cloud is, you know, it’s unlimited capacity, in theory,” he says. And with engineering teams across the globe, including in China and Malaysia, Zoom has the technical chops to be able to remotely monitor its systems around the clock.

Still, some Zoom users have noticed dips in video quality, or had difficulty connecting in the first place. Zoom’s online help centre is experiencing the dreaded “longer wait times than normal”. On March 23, Zoom’s service page acknowledged that some users of its free service were reporting problems with starting and joining meetings. That’s not surprising, given that daily active mobile users jumped by 610 percent in the last two months, per Apptopia. It’s not just Zoom’s challenge. The internet as a whole is straining from so many people now living entirely online, says Morgan Kurk, CTO of communications technology firm CommScope. His recommendation: Schedule your Zoom—or any virtual meeting—roughly 15 minutes past the hour to avoid the virtual rush.

With ubiquity has come more scrutiny from security and privacy researchers. In late March, Vice Media’s tech-news site, Motherboard, revealed that Zoom was sending data to Facebook, even if users didn’t have a Facebook account. Zoom said the outflow was limited to metadata—what type of device you were using, the size of your screen, what language and time zone you were in. One day after the news broke, Yuan wrote an apologetic blog post explaining that the program had allowed users to log in via Facebook, and that code had now been removed.

Zoom collects user data only to the extent it’s absolutely necessary, it says, to provide “technical and operational support”—in other words, to ensure your meeting’s audio and video are working smoothly. One school in Colorado says it won’t use Zoom, citing concerns about how its data would be used and who controls it long-term. Zoom does not have the ability to monitor anyone’s conversations or meetings in real time, says global risk and compliance officer Lynn Haaland, who recently joined the company from PepsiCo. And while Zoom has also caught flak for an attention-tracking tool that can tell administrators who turned it on when attendees have opened something else over the Zoom meeting for more than 30 seconds, Haaland says that Zoom does not track what users have open besides Zoom. “We are committed to protecting the privacy and security of students’ data, as we are all with all customers,” she says.

What about protecting users from hackers? On March 30, the office of New York Attorney General Letitia James sent a letter to Zoom outlining several privacy concerns, including whether the surge in users made the platform more vulnerable to hackers. “During the Covid-19 pandemic, we are working around the clock to ensure that hospitals, universities, schools and other businesses across the world can stay connected and operational,” Zoom said in a statement sent to Forbes. “We appreciate the New York attorney general’s engagement on these issues and are happy to provide her with the requested information.”

In his temporary home-office headquarters, Yuan says demand has pushed him into a 7.30 am to 11.30 pm work routine: “I just feel busier at home. My mom [who lives with us] keeps asking me, ‘How come you have meetings like this every day? You missed lunch!’”

He does find time to check social media, where he has long been known to respond to individual user concerns and vow to look into problems himself. “It’s not something to distract myself. This is part of our business operation,” Yuan says. “At the start of a company like Zoom, there are problems every day. Do you want to know, or do you want to hide? I want to know.”

Some of this has led to improvements such as better virtual backgrounds and a default setting for teachers that locks their students’ screens so they can’t hijack the lesson as a prank. Zoom has also rolled out new capabilities, like a tune-up feature inspired by consumer apps that touches up one’s face and lighting. It is also working on a tool for college-sized classes that would make it so that every student’s video would appear as though shot from the same angle.

Still, Yuan says he wakes up in the middle of the night worrying if Zoom is doing enough. Some schools in some parts of the world that want Zoom don’t yet have it.

And the company has made the decision not to offer a similar program to non-profits or other needy programs. Yuan says that while K-12 school email addresses are easy to verify, there’s no good way for Zoom to automatically review and approve the rest.

What happens to Zoom after the pandemic passes? Analysts expect its stock, trading at a nosebleed multiple to projected revenues, to fall back to earth somewhat as people go back to the office, but see the virus as a “wakeup call” for businesses that will save on rent and commuting time by shifting more permanently to work-from-home. Zoom should be able to turn many free users into paying ones—and profit—in the long run, says RBC analyst Alex Zukin. “Zoom is being a good corporate citizen,” adds JPMorgan Equity Research’s Sterling Auty. “They are not looking to take unfair advantage. We think that goodwill carries a long way.”

Yuan says he has frozen all projects and plans that don’t contribute directly to keeping Zoom running—and helping students—through the crisis. He has instructed his executives not to ramp up sales or marketing to benefit from Zoom’s current boost. He also approved a bonus for all Zoom employees as they work overdrive through the surge in usage, equivalent to two weeks’ pay. “I told the team that with any crisis like this, let’s not leverage the opportunity for marketing or sales. Let’s focus on our customers,” Yuan says. “If you leverage this opportunity for money, I think that’s a horrible culture.”

Image: Kena Betancur / Getty Images[br]Zoom CEO Eric Yuan’s kids finally care about what he does for a living. Sure, they were there that morning in April 2019 when Yuan, the founder of the world’s most popular videoconferencing company, rang the opening bell at Nasdaq, with Zoom’s stock-market debut making him a billionaire. But it wasn’t until a Monday in mid-March that Yuan’s eighth-grade daughter, forced by the coronavirus to go to school remotely, finally had a question about her father’s work. “My daughter had never asked what I’m doing,” Yuan says, beaming. “For the first time, she stopped by to say, ‘Dad, how do your raise your hand in Zoom?’”

Image: Kena Betancur / Getty Images[br]Zoom CEO Eric Yuan’s kids finally care about what he does for a living. Sure, they were there that morning in April 2019 when Yuan, the founder of the world’s most popular videoconferencing company, rang the opening bell at Nasdaq, with Zoom’s stock-market debut making him a billionaire. But it wasn’t until a Monday in mid-March that Yuan’s eighth-grade daughter, forced by the coronavirus to go to school remotely, finally had a question about her father’s work. “My daughter had never asked what I’m doing,” Yuan says, beaming. “For the first time, she stopped by to say, ‘Dad, how do your raise your hand in Zoom?’” Zoom’s Latin America team enjoys a virtual happy hour[br]Zoom isn’t just a darling of Wall Street. It’s a social media phenomenon. On Twitter, TikTok and elsewhere, Zoom has gone viral—quite a feat for a piece of business software. “Just got an email from a prof: ‘As a reminder, you are required to wear clothes during Zoom meetings’. Rules are made when they become necessary, not before,” one Twitter user quipped, getting more than 85,000 likes. Joked another, to 21,000 likes: “Lol you thought you were better than me cause you went to Harvard??? We’re all attending Zoom University now.” (The real Harvard is conducting all of its remaining classes on, what else, Zoom.)

Zoom’s Latin America team enjoys a virtual happy hour[br]Zoom isn’t just a darling of Wall Street. It’s a social media phenomenon. On Twitter, TikTok and elsewhere, Zoom has gone viral—quite a feat for a piece of business software. “Just got an email from a prof: ‘As a reminder, you are required to wear clothes during Zoom meetings’. Rules are made when they become necessary, not before,” one Twitter user quipped, getting more than 85,000 likes. Joked another, to 21,000 likes: “Lol you thought you were better than me cause you went to Harvard??? We’re all attending Zoom University now.” (The real Harvard is conducting all of its remaining classes on, what else, Zoom.) Kindergarten teacher James Baldwin reads a children’s book to his students (next page) from his home in Brookline, Massachusetts, a Boston suburb

Kindergarten teacher James Baldwin reads a children’s book to his students (next page) from his home in Brookline, Massachusetts, a Boston suburb Jessica Rinaldi / The Boston Globe via Getty Images[br]Now that altruistic impulse is taking on global importance as Zoom has become vital for the work-from-home economy. But it’s far from the only company stepping up to meet this trend—and standing to profit later. Google and Microsoft also announced they were opening up more free features for their own classroom and videoconferencing tools. RingCentral, a Belmont, California–based cloud communications company, and Newsela, a New York City–based ed-tech firm, are two of a host of lesser-known players doing the same.

Jessica Rinaldi / The Boston Globe via Getty Images[br]Now that altruistic impulse is taking on global importance as Zoom has become vital for the work-from-home economy. But it’s far from the only company stepping up to meet this trend—and standing to profit later. Google and Microsoft also announced they were opening up more free features for their own classroom and videoconferencing tools. RingCentral, a Belmont, California–based cloud communications company, and Newsela, a New York City–based ed-tech firm, are two of a host of lesser-known players doing the same.