Harry, 69, as he is known to friends, had spent his career in shipping and commodity trading. In the 1980s, he and his partner, Noble group chairman Richard Elman, went on to create from scratch the largest commodity trading firm in Asia. From seven people in a tiny room in Hong Kong, the firm went on to pioneer commodity trading in China. By early 2010, its market cap had risen to $11 billion.

Along the way, the Amritsar-born Banga and Elman had seen China transform itself into the world’s second largest economy. As it went from producing 150 million tonnes of steel a year to 600 million in the 2000s, the ensuing commodity supercycle was one the world had never seen nor is likely to see again. Banga was in the thick of things travelling across China, staying in rest houses without heat or running water, forming relationships with steel mills that would last a lifetime.

In those heady days, the iron ore shipment that Noble had sent from Goa to China for $12 a tonne in the 1990s was being sold at $200 a tonne. The market was somewhere close to the top. “When you start seeing this for things that are essentially picked from the ground and shipped out, you start thinking isn’t this [price] enough?” asks Banga. Global miners Rio Tinto, BHP and Vale had chosen to expand capacity furiously in a peaking market.

The Noble group saw it differently. There was more money to be made in owning mines, sugar mills, storage facilities and ports rather than just trading iron ore. A fully integrated player could capture more of the value chain. A balance sheet leveraged in an upcycle can make profits soar but they sink the company when the going gets tough.

Banga, who’d seen several peaks and troughs created by greed and fear, knew the end was near. One was better off keeping the powder dry. With assets overvalued, he argued they’d already missed that opportunity. In 2010, after disagreeing on the path ahead, he began to wind down his association with the trading house he’d built. When the last of his shares were sold in 2013, he’d netted $950 million for his 11.5 percent stake.

The timing proved fortuitous. The puncturing of the commodity boom bankrupted his former employer. Two sugar mills bought by Noble from Brazil’s Grupo Cerradinho for $950 million in the boom accounted for a lion’s share of the losses. Banga on the other hand was 63 and in no mood to retire. He was on track to start his second innings as an entrepreneur at the Caravel Group named after a small 15th century Spanish sailing ship that is easily manoueverable.

At Caravel, Banga has followed the same playbook as Noble—maritime services and commodity trading, along with a new layer of asset management that allows him to diversify his holdings away from the cyclical businesses. When Banga initially proposed that his son Angad join him, the junior Banga said “Dad, that’s a bad idea. I don’t know anything about ships.” He agreed to come on board on the condition that they start an investment management division, which the senior Banga thought was the bad idea. “We took two bad ideas, put them together and started Caravel,” he jokes.

Angad, 36, who joined the business, graduated from Dartmouth College and worked for JP Morgan and KKR before joining Caravel. Elder brother Guneet, 40, graduated from Princeton, has an MBA from Wharton and is now a partner at Aera VC.

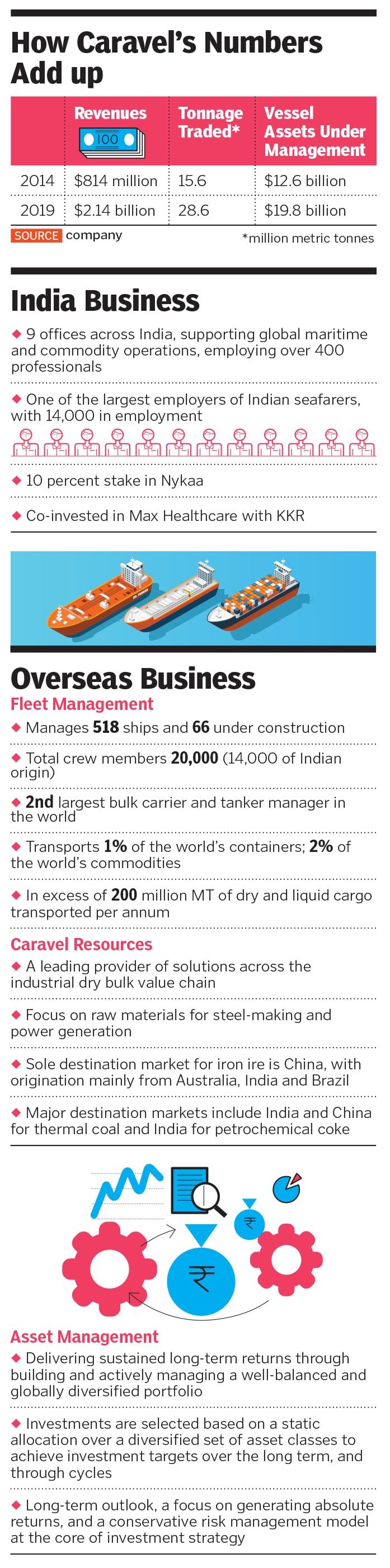

In the seven years since it’s been operational, Caravel has done brisk business. Tonnage hauled has risen from 15.6 million to 28.6 million metric tonnes while revenues have risen from $814 million to $2.14 billion between 2014 and 2019. On the fleet management side, assets under management have increased from $12.6 billion to $19.8 billion. With a net wealth of $1.5 billion Banga, an art aficionado, ranks 1,415 on the billionaires list.

Caravel started with a business that Banga knew intimately. During his time at Noble, he’d set up a Mumbai-based company that specialised in fleet management. Think of it as a hotel management company. The asset owned by someone else is managed for a fee. With Banga slated to leave, the board didn’t want to run the business and, after a couple of independent valuation reports, they agreed on a price of $75 million. On Caravel’s part, Banga knew the company would provide steady cash flows that can be deployed in other ventures. The annuity portion of his portfolio was complete. From providing crews for 346 ships in 2013, the number of ships under management has grown to 584. Based on the valuation a similar company sold at, the business is now worth an estimated $500 million.

With Banga’s exit, Noble’s traders who had worked with him had also been restless to leave and, by 2013, global growth had bounced back. Coal and iron prices were up and so were shipping rates. Caravel got down to serving clients in China again. Lately, he’s turned bullish on base metal prices again. The Covid-19 situation is bound to result in increased infrastructure spending as countries look to get people back to work. Expect copper, nickel, zinc and aluminium to be back in demand again.![mormugao dock mormugao dock]() Due to a volatile market, most iron ore miners with annual contracts in the late-90s and early-2000s had problems in enforcing deals. But Banga never reneged on his price agreementsw

Due to a volatile market, most iron ore miners with annual contracts in the late-90s and early-2000s had problems in enforcing deals. But Banga never reneged on his price agreementsw

Image: Getty Images[br]Banga sees himself as a service provider to the industry and is known as someone who keeps his word. As the market moved from annual to spot contracts in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the biggest issue miners had was enforcing cross border agreements. There was also a mad scramble for iron ore, and mines in Brazil, Canada, Australia and India found themselves fielding enquiries from new clients. A volatile market meant buyers would demand lower prices if they fell as the delivery date got closer.

“Our biggest problem with working with the Chinese was constant price renegotiation. With Caravel, that has never been a problem,” says Vijay Chowgule, former chairman of the Chowgule Group, which runs iron ore mines in Goa. He’s done business with Noble and the Caravel Group for over two decades. Caravel provides end-to-end solutions to their customers, whether risk management, freight or finance. “We’re not taking too much risk here. I would rather make $1 per tonne over 40 million tonnes than $40 a tonne on 1 million tonnes,” says Banga. Iron ore bought on the spot market is either sold to a buyer or immediately hedged.

![jaspal bindra jaspal bindra]()

The trading book is structured so that no more than 5-6 percent of iron ore trading is proprietary. This is the portion where the risk is higher and where the company takes a positional call on prices over the next 10 days. Traders at the desks in Wan Chai, the Caravel headquarters overlooking the Hong Kong harbour, are incentivised not to make wild bets. A risk management team of 15 keeps a hawk eye with quantity, tonnage and value at risk limits. Son Angad receives a global risk report every morning.

On the topic of risk management, Banga is in his element. In 2008, just before the global financial crisis, the charter rate for a dry bulk carrier was $300,000 a day. By the end of the year, it had fallen to $3,000 a day. Earlier this year, rates were $6,000 a day compared to the $22,000 a day in June. With this level of volatility in prices, shipping lines often find it hard to make mony. The top nine US-listed dry bulk carriers have lost a total of $11.3 billion in the last decade. Daiichi, STX Pan Ocean and TMT filed for bankruptcy. Caravel owns two bulk carriers and has joint ownership of five container ships. These are asset plays where the company is looking for steady chartering income as well as price appreciation.

With large price swings, Banga is clear that he’s unwilling to take high risks while trading commodities. The potential downside a trader could face on account of, say, the recent contagion in the oil market is a strict no-no. On April 21, oil for June delivery fell to minus $37.63 with the spot price being lower than the futures price. With most economies locked down, traders had run out of place to store and tankers were being contracted for $300,000 a day (up from $10,000 a day). Sure, some traders made super normal profits but Hin Leon Trading Pte, a Singapore-based oil trader, got cleaned out. Those are not the kind of bets Caravel, which has zero debt on its balance sheet, is willing to make. Quick turnover of positions and rotating capital multiple times a year can result in similar internal rate of returns with far lower risk levels.

With the trading and shipping business cruising along, Angad has been tasked with setting up a family office that deploys their liquid assets. Having spent time with JP Morgan and KKR, he was acutely aware of the need to move beyond their traditional businesses to reduce concentration risk. The recent pandemic has only made that choice more stark. Caravel had 35 ships doing business at Chinese ports. While there hasn’t been a single case of infection on board their ships, crew have been unable to return home In the post-SARS world—post-2003—the risk of a pandemic had been at the back of their minds although Angad admits they hadn’t modelled for it.

Caravel aims to manage its portfolio with the same expertise as institutional asset managers: About three-fourths of their assets are deployed in long-short global credit and equity funds. They’ve also signed on as a limited partner to hedge funds and PE firms as well as a fledgling in house PE division. In 2014, Angad made his first India investment in online startup Nykaa. They’ve also co-invested with KKR in Max Healthcare. The recent political tensions between India and China could open up a potential risk. Banga declined to comment.

![angad banga angad banga]()

As he looks back at his three-decade-and-counting journey and all that he’s accomplished, for Banga, some things will never change. The importance of relationships is one. He makes it a point to stay in touch with business associates and has built a formidable network across mainland China. Those days of staying in decrepit resthouses have paid off. While his Mandarin skills are not what they once were, he still has a working knowledge of the language. Even today, he makes it a point to meet visitors as they transit through Hong Kong on their way to Japan and China or the Far East. “Sometimes there are just too many dinner engagements in a week,” he says, bemoaning he has little free time for a hobby.

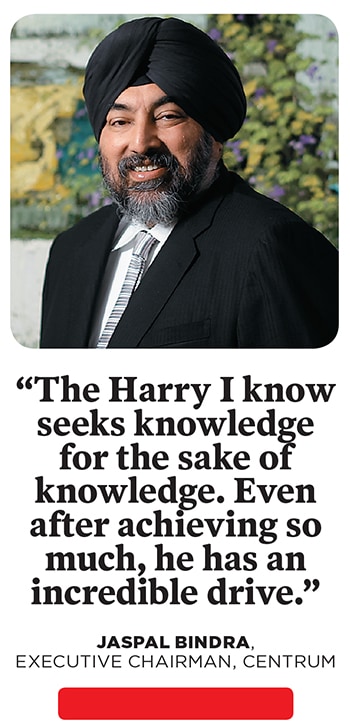

He maintains an innate sense of curiosity, which got him so far. “The Harry I know seeks knowledge for the sake of knowledge. Even after achieving so much he still has an incredible drive,” says Jaspal Bindra, executive chairman of the Centrum Group, who has known Banga from the time they were in Chandigarh in the 1960s. He’s constantly thinking of his next move and playing out scenarios in his head. His quick thinking was evident when the Covid crisis hit. Every year, he’d make a trip to Beijing and Dalian the week after the Chinese New Year. When news about the infections started coming in, he immediately asked his people on the ground for their intelligence and made contingency plans for their ships docked at ports. “Getting food and water on board was a priority for me,” he says.

Seven years after its founding, Caravel has a sound base from which to plot future expansions. Fleet management provides predictability to earnings, the commodity cycle could see an upswing and so could shipping rates. Nykaa and Max Healthcare have long runways ahead and Angad is confident about their prospects. They’ve invested in every subsequent round in Nykaa to either keep or increase their stake, which stands at 10 percent.

Angad is keen on backing the technology space. With the productivity gains the sector has delivered over the last decade, it has been a happy hunting ground for investors. Technological improvements in the shipping business could bring in investing opportunities. “While I am unsure if we could have autonomous ships five years from now, there are certainly several parts of the industry that could see increased technological involvement,” says Angad. Expect capital to be deployed there.

A zero-debt balance sheet and the opportunities brought on by Covid-19 should see Caravel exploring deals in businesses that haven’t had their prospects changed. Banga is not averse to leveraging whis balance sheet if the right opportunity comes along but says he won’t diversify for the sake of it. So no buying a hotel chain, for instance, but he’s keeping his chequebook open for a steady flow of proposals that should start coming in as companies look for capital in the post-pandemic world.

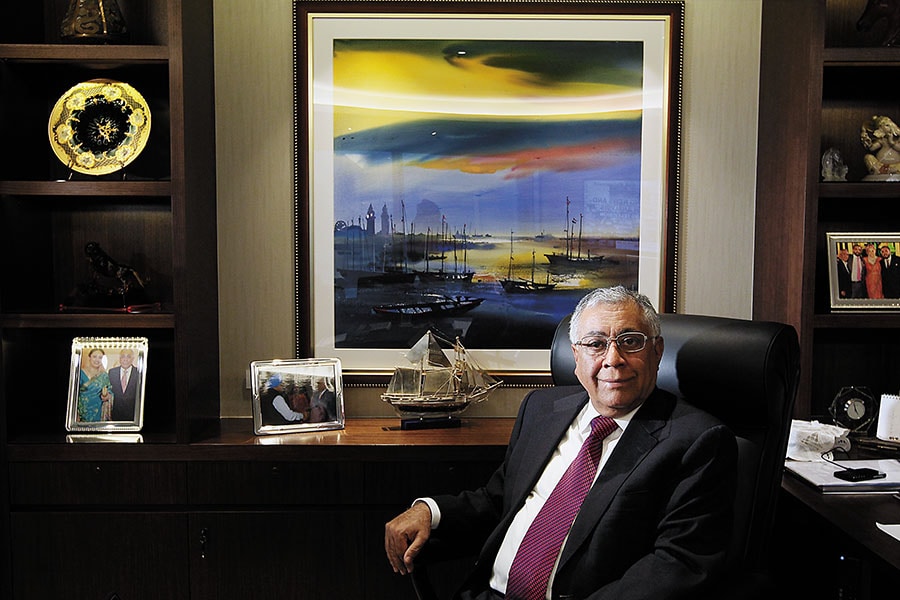

Harindarpal ‘Harry’ Banga at the Caravel headquarters at Wan Chai in Hong Kong

Harindarpal ‘Harry’ Banga at the Caravel headquarters at Wan Chai in Hong Kong

Due to a volatile market, most iron ore miners with annual contracts in the late-90s and early-2000s had problems in enforcing deals. But Banga never reneged on his price agreementsw

Due to a volatile market, most iron ore miners with annual contracts in the late-90s and early-2000s had problems in enforcing deals. But Banga never reneged on his price agreementsw