Making a picture is the last thing that happens: Jimmy Nelson

The ace photographer talks about the importance of portraying indigenous people and cultures

.jpg) "I do not speak their language, but have a sincere respect for them. When I shoot indigenous people, I put myself in a physically fragile position."British photojournalist and photographer James (Jimmy) Nelson has spent a lifetime photographing indigenous tribes around the world. His work, which is often the result of months of travel and living among his subjects, has culminated in books such as Literary Portraits of China, Before They Pass Away, and Homage to Humanity. His photographs, highly stylised and staged, have also attracted criticism from various quarters, primarily for failing to show the realities of indigenous populations, and misrepresentation.

"I do not speak their language, but have a sincere respect for them. When I shoot indigenous people, I put myself in a physically fragile position."British photojournalist and photographer James (Jimmy) Nelson has spent a lifetime photographing indigenous tribes around the world. His work, which is often the result of months of travel and living among his subjects, has culminated in books such as Literary Portraits of China, Before They Pass Away, and Homage to Humanity. His photographs, highly stylised and staged, have also attracted criticism from various quarters, primarily for failing to show the realities of indigenous populations, and misrepresentation.

Nelson has now teamed up with J Walter Thompson, a marketing company, to launch a campaign called ‘Blink. And They Are Gone’ to raise awareness about the urgent need to preserve indigenous cultural heritage. It has started with the making of a short film, from more than 1,500 unseen photographs taken by Nelson of 36 indigenous communities across the world.

“The idea behind the campaign was that indigenous tribes and cultures are disappearing. Nelson has spent months with each of these tribes, and we wanted to help him share his work,” says Senthil Kumar, chief creative officer at J Walter Thompson India. “For all of us, it is a journey back to our roots.”

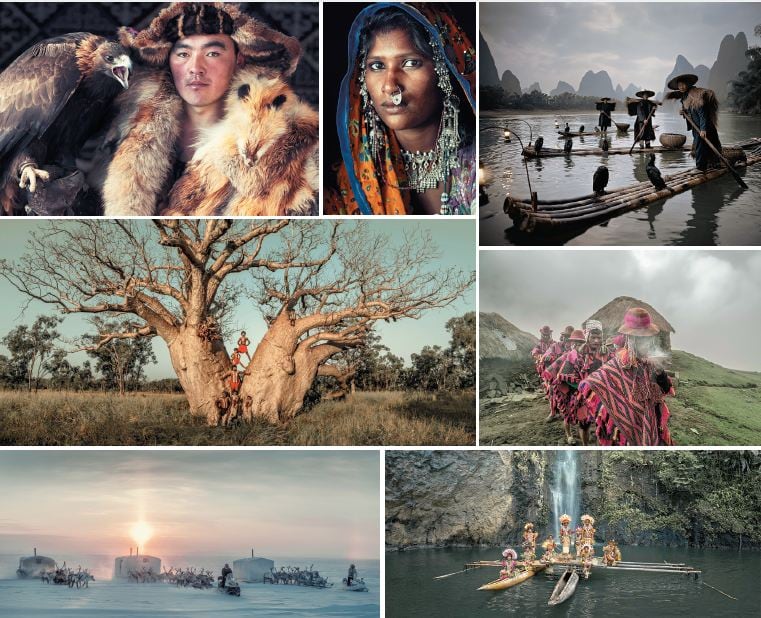

(Clockwise from top) A member of Mongolia’s Kazakh tribe a woman from the Mir tribe of Gujarat the traditional cormorant fishermen of China the Q’ero tribe of Peru the Korafe tribe of Papua New Guinea the Dolgans of Siberia the Mowanjum community of Australia

(Clockwise from top) A member of Mongolia’s Kazakh tribe a woman from the Mir tribe of Gujarat the traditional cormorant fishermen of China the Q’ero tribe of Peru the Korafe tribe of Papua New Guinea the Dolgans of Siberia the Mowanjum community of Australia

In an interview with Forbes India, Nelson, 51, talks about his journey as a photographer, and how images are merely the end result of establishing a relationship. Edited excerpts:Q How did you become a photographer?

I became a photographer by accident, and it stemmed from an early childhood interest. At the age of seven, I was sent to an English boarding school that was brutally strict and abusive. You could say that my love for ‘the other’ was a 100 percent reaction to this abusive education system that I experienced in my early years.

My hair fell out by the time I was 16, and I ran away to Tibet. I was actually inspired by Tintin in Tibet, because I saw that the Buddhist monks did not have any hair. I thought that perhaps in that land, I would not be judged for the way I looked.

My journey of photographing indigenous people has been, in a way, a search for my own identity. I started my journey as a curious and isolated human being, and used the camera as a consolidation of a relationship with other people. If your message is pure, then the medium does not matter. I am still not interested in the camera I am fascinated with how we communicate.

Anybody can become a photographer making a picture is not complicated.

Q What is the process of establishing a relationship with your subjects?

I do not speak their language, but have a deep and sincere respect for them. When I go to shoot indigenous people, I put myself in a physically fragile position, by, for instance, sitting on the floor of their homes. I live with them for weeks and months, and establish a respectful relationship with them. Making a picture is the last thing that happens.

Usually, we tend to take a very arrogant and self-righteous stance.

Q What are the common challenges that indigenous people around the world face today?

The world is becoming more and more globalised, digitised and connected. There is confusion and fear among indigenous people, regarding the validity of their way of life and knowledge. They have a feeling of holding on to the heritage that they have.

A lot of indigenous populations live on land that is rich in natural resources. There are questions being raised about who owns the land they live on, especially with governments and corporations exploiting that land.

Q What is it that you wish to portray through your photographs?

My work is a subjective and a celebratory way of looking at these communities. My aim is to make people and governments realise that these communities are a different cultural resource that they are fragile, and demand our respect and humility.

Q What are the lessons that you have learnt from your interactions with indigenous people?

The most important lesson that I have learnt is that of reciprocity the fact that I have to give something in order to receive something in return. We, in the developed world, are very selfish, and we want more and more. The indigenous people that I have met have always given me far more to make me comfortable.

What I have also learnt is the connection that we can establish with nature, the environment and the natural world around us. When there is no concrete on the floor, and we walk bare feet on the soil, you can feel the planet a planet that was functioning very well before we arrived.

First Published: Mar 23, 2019, 07:00

Subscribe Now