Travel: Take a trip—or dip—through Germany's Wiesbaden

The spa town dates back to medieval times

_s.jpg?im=Resize,width=600,aspect=fit,type=normal)

_s.jpg?im=Resize,width=600,aspect=fit,type=normal)

.jpg) Wiesbaden’s most prominent hot spring is Kochbrunnen where one can drink filtered water

Wiesbaden’s most prominent hot spring is Kochbrunnen where one can drink filtered water

Image: Khursheed Dinshaw

The Romans, as with many other things they built, did not confine bath houses to Rome, and built them at several locations across the vast Roman Empire. In Germany, for instance, when the Romans lived in Mainz, they noticed that when they sent their horses to graze on the other side of the river Rhine, the animals seemed particularly happy and rejuvenated. The discovery of naturally occurring hot water springs in the region led the Romans to set up their bathing metropolis there, calling it Wiesbaden (wiesen means fields, baden means bathing). With 26 thermal springs, it was a befitting name.Today, in Wiesbaden, tourists can easily visit the hot springs and fountains, and drink their mineral-rich water, although it is not meant for daily consumption, since its potency makes it unsuitable to drink for long durations, unless medically advised. Like other hot springs around the world—they are found in Iceland, New Zealand, Australia, Japan, Turkey and the US—Wiesbaden’s springs are geothermally heated by deep-seated rocks beneath the earth’s crust. As the heated water flows through faults in the crust, a combination of heat and pressure causes it to gush out of the ground surface.

Wiesbaden’s springs supply almost 2 million litres of hot water every day, and have given rise to several modern day bath facilities that attract curious tourists from around the world. The city’s most prominent hot spring is Kochbrunnen, located at the historic square of Kranzplatz, where it is now surrounded by the state chancellery of the federal state of Hessen, and luxurious hotels like the Schwarzer Bock and Palast Hotel. Kranzplatz was a thermal facility for the Romans, while Schwarzer Bock dates back to the 15th century, and has its own spring.

Like in the past, Kochbrunnen stands its own ground amidst its historic counterparts, gushing out almost 880 litres of water in a minute. Shaped like a shell, its water is hot, at 68°C, and gives rise to slight steam bubbling at the top of the opening from which it sputters out. Next to Kochbrunnen is a small fountain from which visitors can drink its filtered water. The hot water is extremely salty, courtesy the high concentration of sodium. It also contains calcium, potassium, magnesium, strontium and hydrogen carbonate.

Sinter deposits from the water form uneven coatings of red and yellow sedimentation. In ancient times, these sediments were in high demand among Roman women who had dark hair, and who aspired to meet the beauty benchmarks of having red hair. Twice a year the sinter deposits were scrapped off, and sold as Mattiac balls, which were used to add a red tint to dark hair.

The significance of hot springs in Roman life can be gauged by the fact that Gaius Plinius Secundus, known as Pliny the Elder, who was a Roman writer and commander wrote about them, and the Roman poet Martial wrote about ‘mattiakischenKugel’ which helped prevent hair loss.

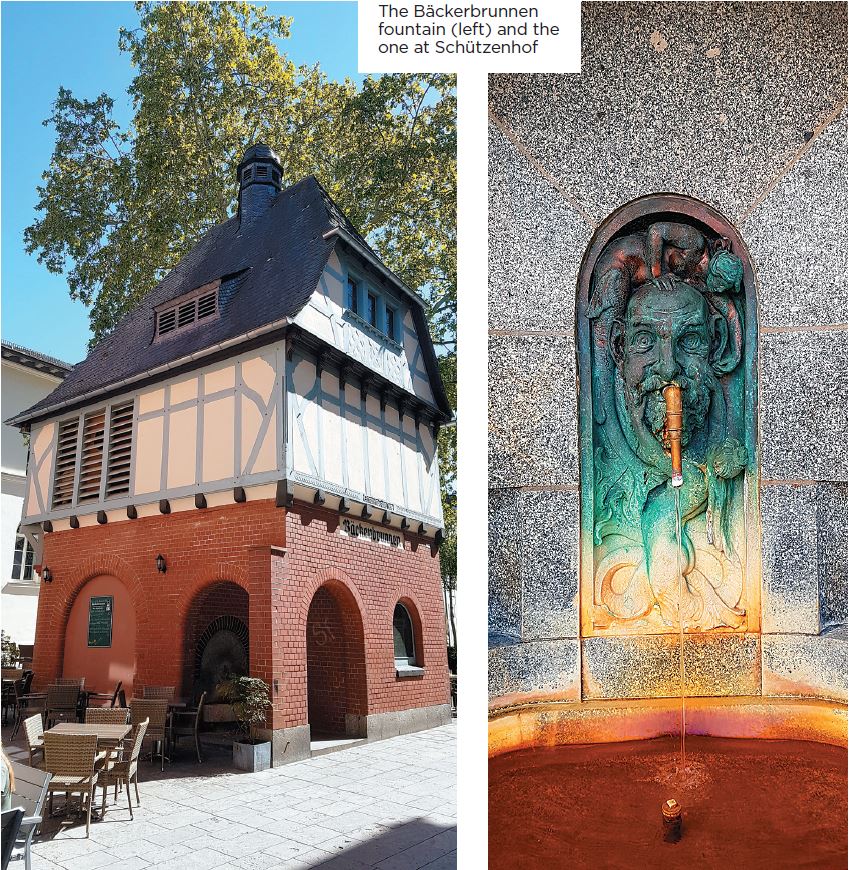

The current day utility of this water is to heat some of the nearby buildings. The rest of it is filtered and directed through pipes to Thermalbad Aukammtal and Kaiser-Friedrich-Therme, a couple of the popular thermal facilities of Wiesbaden, the latter being built on the foundations of a former Roman sweat bath.A short walk away from Kochbrunnen, through cobbled lanes, is the fountain called Bäckerbrunnen, which is located in the quarter of Altstadtschiffchen. In the middle ages, Bäckerbrunnen was surrounded by bakeries and its water was used for baking specific kinds of bread. It was a combination of four different springs that were subsequently used for bathing and curative purposes.

The fountain now stands surrounded by vibrant cafés, bakeries and shops. The structure housing it was probably built in 1906, with its lower half made of bricks, and its upper half resembling a timber house complete with windows and a chimney. Such half-timber houses are an architectural specialty of Germany, and date back to 1700 to 1830. Made using local materials, they are unique because within the timber frame, hay and clay are stuffed to keep the house warm during the harsh German winters.

From Bäckerbrunnen, I make my way to the third-most popular spring called Schützenhofquelle, where the Romans built the first spa for their soldiers. The water is a few degrees cooler than the previous two, and contains sodium, calcium, potassium, magnesium, strontium, hydrogen carbonate and sulphate. In the 15th century, water from this spring was used in the bathing facility of Schützenhof, while in the 19th century, its water was used by a grand hotel by the same name. Today, the spring is surrounded by shops selling clothes and accessories.

The Langgasse of today was probably the main street which housed all the Roman baths in medieval times. However, even today, walking down this street, now lined with shops in the heart of Wiesbaden, it is obvious how the city first got its name.

The writer travelled to Wiesbaden on invitation of the German National Tourist Office, India

First Published: Jun 29, 2019, 06:05

Subscribe Now