China conflict: Why the US needs Indonesia

The Biden administration has spent much of its first year in office shoring up support among allies and partners who share Washington's concerns about Beijing but were bruised by four years of Donald

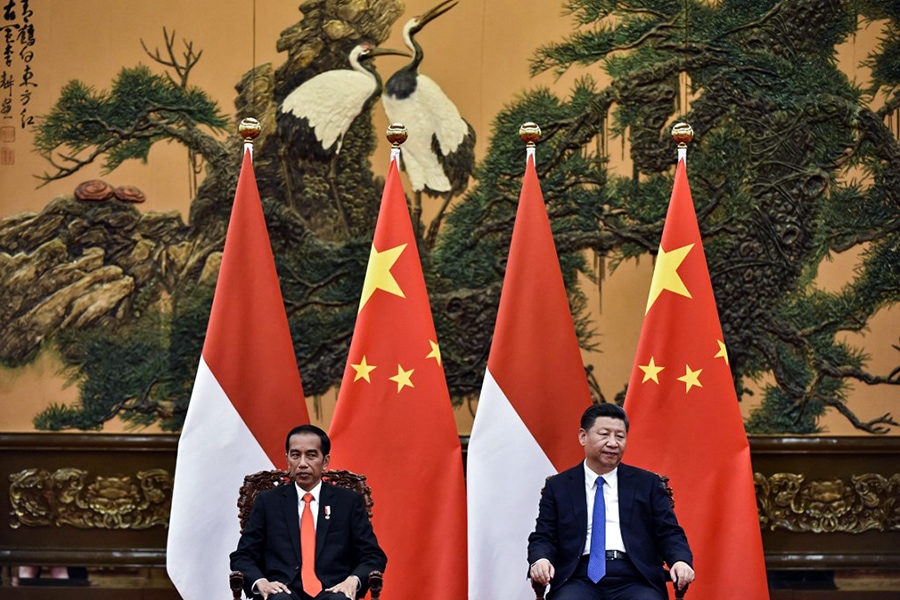

President Joko Widodo of Indonesia, left, and President Xi Jinping of China in 2017.

President Joko Widodo of Indonesia, left, and President Xi Jinping of China in 2017.

Image: Kenzaburo Fukuhara / Pool / AFP

When President Biden met his Indonesian counterpart, Joko Widodo, last month in Glasgow, he praised Indonesia’s “essential" leadership in the Indo-Pacific and “strong commitment" to democratic values.

But the reality of American engagement with the world’s third-most-populous democracy has been more tepid than these warm words imply, belying Indonesia’s position as the leading Southeast Asian power and a vital balancing force in the geopolitical contest of our time between the United States and China.

The Biden administration has spent much of its first year in office shoring up support among allies and partners who share Washington’s concerns about Beijing but were bruised by four years of Donald Trump. That period of reassurance was important and necessary. But if the real goal of strategic competition with China is to ensure a “free and open Indo-Pacific" — rather than pursuing great-power competition for its own sake — America cannot rely on a few fast friends who share its worldview.

Washington needs to move closer to nonaligned, and sometimes quarrelsome, emerging powers like Indonesia and help them become less reliant on China.

A proud nation of 275 million people, Indonesia jealously guards its autonomy in international affairs, knowing full well how damaging foreign interventions can be — from colonial rule to violent coups and uprisings supported by America in the 1950s and ’60s.

Indonesia established an “independent and active" foreign policy after declaring independence from the Netherlands in 1945. It still refuses to sign alliances with any other powers, is a committed member of the Non-Aligned Movement and reacts angrily to perceived threats to its sovereignty.

Relations with Washington have seesawed over the decades. The United States ended a lengthy period of confrontation with Sukarno, Indonesia’s founding president, by backing his ouster and propelling the rise of Suharto, a taciturn general who ruled as a dictator for 32 years until 1998. But the Indonesian government soured on Washington because it felt that President Bill Clinton had pressured Indonesia to accept a punishing I.M.F. bailout in 1998 and later grant an independence referendum to East Timor.

Today, Indonesia maintains close ties with U.S. adversaries Russia and Iran. And there’s its growing relationship with China. Under President Joko, known as Jokowi, China has become one of Indonesia’s biggest investors, spending billions of dollars on new highways, power plants and a high-speed rail line. It also provided Indonesia with around 80 percent of its Covid-19 vaccines.

While Indonesia cooperates with the United States on military, counterterrorism and development programs, it also is wary about new American security initiatives in the region — like the AUKUS partnership, which aims to equip neighboring Australia with nuclear-powered submarines.

Now is the perfect time for Washington and its allies to woo Indonesia. The goal should not be to peel Indonesia away from China but to support Mr. Joko’s plans for economic and social development — he is looking to cement his legacy before he’s due to step down in 2024 — and help the country become an alternative pole of strength to challenge the emerging sense in Asia that China alone holds the keys to the region’s future.

So far, Washington has shown limited ambition for boosting the relationship with Indonesia. Despite warnings over Beijing’s growing strategic leverage with Jakarta, it has yet to come up with significant economic counterweights.

But closer relations with China don’t mean that Mr. Joko is choosing a side in great-power competition. Rather, he is approaching foreign policy with the practicality of the furniture factory owner and mayor he used to be, willing to work with whoever can help him meet core objectives — like boosting the economy.

Kurt Campbell, who leads Indo-Pacific policy in the White House, once told me that if you ranked the countries most important to the United States but least understood, Indonesia would be first. The world’s fourth-most-populous nation, the world’s most populous Muslim-majority nation and the world’s largest archipelago nation: Generating interest in Indonesia usually requires a list of superlatives.

Between domestic issues and a long list of foreign policy challenges to address, it seems that Indonesia is falling off the agenda again, even as the Biden administration starts to step up in Southeast Asia. The president’s interim national security strategic guidance, released in March, name-checked Singapore and Vietnam, which support U.S. pushback against China, as important Southeast Asian partners, but not Indonesia.

When Vice President Kamala Harris and Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin made separate trips to Southeast Asia earlier this year, they skipped Indonesia — which The Jakarta Post, the country’s leading English language newspaper, called a “snub."

The good news is that Mr. Joko does not bear grudges. While writing his first English-language political biography, I watched him work with all comers to get what he wants, from street hawkers to billionaires to hard-line Islamist preachers.

A planned visit to Jakarta this week by Secretary of State Antony Blinken is a much-needed corrective to earlier oversights. But one trip does not build a relationship, especially when Chinese ministers have had more regular face-to-face contact with Indonesian counterparts. The Biden administration should use this visit to kick-start a sustained charm offensive to bring the world’s third-largest democracy closer.

Much like Mr. Biden, Mr. Joko is a doer, not a thinker. So the United States should concentrate on areas of practical cooperation with Indonesia — like trade and investment, financing for Jakarta’s plans to curb coal-fired power and deforestation, and greater support for Indonesia’s Covid-19 vaccination campaign.

Helping Indonesia emerge from the economic and health crisis spurred by the pandemic will win favor with Mr. Joko while reducing his reliance on Beijing. Supporting Indonesia’s recovery also will bolster the argument that democracy — not authoritarianism — can deliver for developing countries in Asia.

If the Biden administration wants to dispel China’s line that Washington is an unreliable, declining power, then its proposed Indo-Pacific economic framework, due early next year, must bring real heft. As Southeast Asia’s largest economy, Indonesia merits its own special attention too.

A stronger, wealthier, democratic Indonesia won’t always agree with the United States — but it will add a critical counterweight to China in Asia.

First Published: Dec 13, 2021, 14:23

Subscribe Now