Field vs Failed experiments: What we learn from 2019 Nobel Laureates

Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo show us that live experiments for economic issues in India can take us to a crucial path: Evidence-based policy making

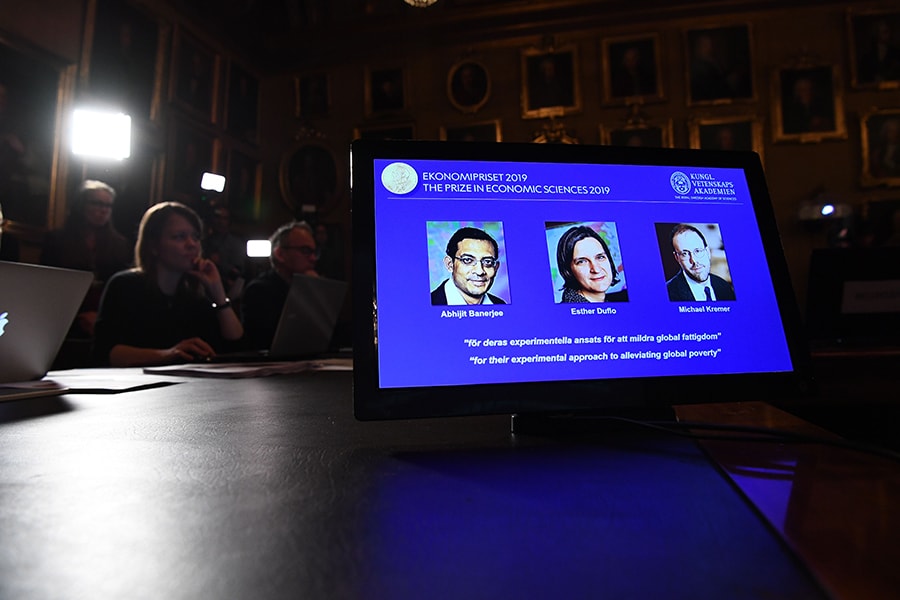

Image: Jonathan Nackstrand /AFP Via Getty Images[br]The 2019 Nobel Prize in Economics has been awarded to Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer “for their experimental approach to alleviate global poverty.” Understandably, the excitement is palpable-from TV Studios and on social media, for Professor Banerjee, an Indian origin economist, always known to express strong views. While a part of me is almost basking in reflected glory, I am more excited about what this years’ Nobel is awarded for, rather than to whom. For economists, the challenge their discipline posits and to find a roadmap to address them, caused them to popularise field experiments. These experiments address the issue "how do we take out millions out of poverty?". There are lessons in it for India as well. But let us start with the challenges they addressed.

Image: Jonathan Nackstrand /AFP Via Getty Images[br]The 2019 Nobel Prize in Economics has been awarded to Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer “for their experimental approach to alleviate global poverty.” Understandably, the excitement is palpable-from TV Studios and on social media, for Professor Banerjee, an Indian origin economist, always known to express strong views. While a part of me is almost basking in reflected glory, I am more excited about what this years’ Nobel is awarded for, rather than to whom. For economists, the challenge their discipline posits and to find a roadmap to address them, caused them to popularise field experiments. These experiments address the issue "how do we take out millions out of poverty?". There are lessons in it for India as well. But let us start with the challenges they addressed.

To understand the challenge an economist faces, let us start with the discipline itself. Economics is a subject that studies how people respond to incentives. Take an example: If 100 wooden blocks are currently bought by people at Rs10 each, the total amount spent in the economy on these blocks is Rs 1,000. If the government decides to impose a 10% tax on each blocks, simple arithmetic would suggest that the government would collect Rs 100 as tax revenue.

Economics would suggest otherwise. With a new effective price of Rs11 per block, the demand may go down and hence perhaps only 90 will be bought with a resultant tax revenue of Rs90. The challenge is now obvious to see. Policy announcements are made based on the current information. However, its effectiveness depends upon how people respond to it a task that often cannot be predicted accurately. As a result, broad based announcements achieve little.

Specific problems would need specific interventions. Consider the case of poverty. The causes of poverty can range from lack of skill or education to ill health to an unanticipated shock to lack of economic assets. To move people out of poverty, one needs to identify the specific cause and then design specific interventions to address them. This is where field experiments play such an important role.

Field experiments are based on asking the counter factual—if people who are exposed to this scenario were not exposed, how would things be different? This is the most effective way of answering whether an intervention is effective or not. It often identifies the cause of distress and thereby suggests ways to address them.

Low school attendance may be due to low teacher-student ratio or lack of adequate infrastructure, or perhaps since too many kids fall sick too frequently, for instance. If the latter is the case, schools having a simple hand wash could help prevent communicable diseases. Kremers’ pioneering work in this area allows us to often find simple solutions to complex problems. Consider the case of micro-finance institutions in India. Do they have any impact on the household income or even women empowerment? Banerjee and Duflo provides credible answers to such questions and many more. Field experiments thus provide valuable insights to causes as well as remedies to address issues that peg households below the poverty line.

How do field experiments work? They begin with a hypothesis, one that is strongly grounded in theory. Field experiments go on to prove or dismiss that hypotheses after filtering out all the noise. The most prominent noise is that of self selection. For example, to assess whether giving a sewing machine or an equivalent cash amount will improve income of a poor household, one cannot base that on volunteers. People who opt for sewing machines may inherently have better stitching skills than those who do not hence, comparing the outcomes of the two groups are misplaced. How does one solve the problem then?

Economists have been known to adopt skills from other disciplines and tailor them to their needs. The idea about answering the counterfactual stems from medical trials. To test the effect of a new drug, one must observe a patient with and without the drug. Medical trials split the population into two random groups—the treatment group that receives the drug, and the control group that receives a placebo. The outcome is now comparable across the two groups. This is what lies at the heart of Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs). However, although well established in medical literature, replication of RCTs in economics is not straightforward.

RCTs, when applied to economic problems, create new problems given that these interventions are to be monitored for at least a year. Going back to our sewing machine example, while the weavers are now earning more, they may not be the best marketers for their products. Others in the village who did not receive a sewing machine may now take up the task of marketing suddenly, both groups have benefitted, thus ruling out any income differences between the two groups. Would we then infer that having a sewing machine has no incremental benefits over not having one?

Furthermore, when such an intervention is known to outsiders, financial institutions may now decide to give loans for the individuals to start making pickles. Suddenly, the weavers have stopped weaving and everyone is now involved in anther economic activity—a possibility that has contaminated the study. Fortunately, the contribution to the literature by the three address many of these problems either by smart designing or by complex analysis. Such field experiments are now not only tractable, it is gradually becoming the yardstick to measure policy effectiveness.

How does this benefit India? Apart from Banerjee and Duflo, both working on various field experiments in India, covering issues related to education, health, financial inclusion and others, these experiments allow us to perform a crucial function—evidence based policy making. In India, cutting across governments, too many schemes are being announced. However, there has been virtually no attempt to evaluate how effective they have been. As a result, defunct schemes with very few beneficiaries clog the system. We learn very little about what to tweak to get better outcomes and what to discard. Simply put, ours has been a case of failed experiments—the time has come to look seriously at the alternative-field experiments.

Bappaditya Mukhopadhyay, Professor, Great Lakes Institute of Management, Gurgaon.

First Published: Oct 21, 2019, 12:20

Subscribe Now