How we survived: Oye! Same same, but different

How Oye rickshaw, an electric rickshaw aggregator for micro-mobility rode the crisis by adding a twist

Oye Rickshaw’s Mohit Sharma and Akashdeep Singh (left) continued with their ambitious gambit

Oye Rickshaw’s Mohit Sharma and Akashdeep Singh (left) continued with their ambitious gambit

"How We Survived" is a series of stories on businesses—big and small—that innovated or pivoted during the coronavirus crisis to survive. For all the stories in this series, click here

It was not an apple to apple comparison. Mohit Sharma knew it well. The odds, truckloads of them, were heavily loaded against the ‘electric’ entrepreneur. Yet Sharma, co-founder of electric rickshaw aggregation platform for micro-mobility Oye Rickshaw, tried to plug in with his logic. Per kilometre operating rate of electric rickshaws —he made his fervent pitch to get delivery business from BigBasket, Grofers and Zomato in early April—is better than that of two-wheelers. And weight and volume carrying capacity is five times that of bikes.

The potential clients were not impressed. “Are you serious? We have small pick-up trucks and bikes for deliveries,” was one reaction. Sharma tried to sweeten the deal: Oye can deliver more per trip and in less time, both to stores and customers. He came up with another bait: A much more scalable business. Electric rickshaws, Sharma stressed, are present in only 20 percent of Tier I cities such as Delhi and Kolkata the rest are in Tier II towns and beyond. The business, he argued, could go deeper into smaller towns with e-rickshaws.

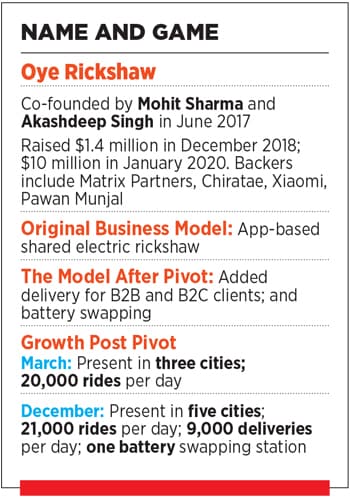

Sharma’s desperation to get the business by pivoting to delivery was understandable. By the end of March, Oye had 1,000 electric rickshaws on its platform, and around 700 were active monthly. The lockdown brought everything to a grinding halt. Drivers were thrown out of business, and so was Oye. Starting with one city and clocking 800 rides per day in December 2018 to being present in three cities and 20,000 rides per day in March, the co-founders were living their dream till then. And then came the shock. “It took us 48 hours to even realise what had happened,” recounts Sharma. ‘Karna kya hai ab (What to do now?)’ was the big question.

The answer: Keep doing the same, with a twist. Electric rickshaws were carrying humans. ‘Can’t humans be replaced with goods?’ was the thought, and it made good business sense. The drivers, who were in exit mode to their native places, would have a compelling reason to stay back, and Oye would be able to keep its business engine running. The co-founders went ahead with their pivoting plan, and roped in Zomato, BigBasket and Grofers among their first clients.

The pace of growth post-pivot has been electrifying. From over 5,000 deliveries per day in September, the daily number has leapfrogged to 9,000 in December. The core—ride-sharing—is also back on track: From 18,000 rides per day in September to 21,000 in December and from three cities in March to five now.

Through Oye’s connected electric vehicle ecosystem, commuters can travel for as little as Rs 15 to Rs 20, and e-rickshaw drivers can grow their incomes by serving multiple use cases across commute and ecommerce deliveries. “The ability for drivers to access energy at the lowest cost makes their model even stronger,” says Rajinder Balaraman, director at Matrix India, one of the investors. These innovations, he lets on, fine-tuned during the Covid period have made Oye one of the most capital and energy efficient ways to solve the mobility needs for Bharat. The prospects look bright. E-rickshaws, underlined the venture capitalist, is the fastest growing segment within mobility, aided by the government’s incentives for drivers and rising aspirations of a digitally connected middle-class.

For Karan Mohla, partner at Chiratae Ventures India Advisors, the biggest bait to stay invested in the venture is the original value proposition: Clean energy-based micro mobility which is affordable and efficient. “They are providing a shared mobility platform for consumers that complements public transportation as well as the first- and last-mile connectivity,” he says. During the pandemic, he points out, the team reimagined the use cases for e-rickshaw. By being able to offer B2B deliveries for large ecommerce and e-grocery platforms, Oye has become an end-to-end solution for businesses and end users. “They have also been the fastest mobility platform to recover to pre-Covid levels,” he contends. Oye is building a future-ready mobility platform best suited to the needs of cities and towns across India, he adds.

In April, Sharma and his co-founder were staring at an uncertain future. “We never did delivery... we were clueless and so were the drivers,” recalls Sharma. Another pressing problem was the rising safety concern about shared rides post Covid. To address all apprehensions, Oye rolled out ‘OyeSafeHai (Oye is safe) Programme’, which had three critical components. First was sanitising the vehicles drivers too would be sanitised and wearing gloves. Second, every rider was asked to download the Aarogya Setu app. And, lastly, every driver was insured. Another teething problem for Oye was inducing a behavioural change in drivers, especially for deliveries. It took a lot of time to make them understand that taking riders and delivering goods needed a different approach.

As a freshly-minted IIT-Delhi grad, Sharma joined Hero MotoCorp in 2012 and worked in strategic sourcing and supply chain for two years. Then came his first stint as an entrepreneur. He co-founded Jangid Motors with his uncle, who had experience in manufacturing the B2B supply business.

The trigger was simple. In 2014, e-rickshaws had just started to enter the Indian market. Within a year, over 500 companies were importing them from China. What all failed to realise was that the vehicles were suited for Chinese roads and made for Chinese conditions. The India part was missing. Sharma and his uncle fixed the problem by rolling out India’s first indigenous electric rickshaw. The business was an instant hit. In three years, they sold over 10,000 vehicles. Sharma then wanted to cater to the micro-mobility needs of users and take them from metro stations and bus stands to homes, markets and nearby offices. This led to the birth of Oye Rickshaw in January 2017 it became operational after nine months.

Interestingly, a year earlier, Ola had taken a stab at electric rickshaws in 2016. It had a first-mover advantage, stayed in the business for two years and then exited. A couple of small players too entered and left the category abruptly. For the Oye co-founders, the omen didn’t look great. What added to their woes was a series of epic operational experiments. Take, for instance, launching a wallet. “Every company had a wallet. This inspired us to create a wallet in our app,” recalls Sharma. Commuters, the duo thought, would use the wallet to pay for the ride and park extra money in the wallet for buying other stuff.

The co-founders continued with their ambitious gambit. After the wallet, came cashback. After all, everyone was getting into the cashback game to lure users. Next was adding one more layer to the app and giving it a lifestyle makeover. “With cashbacks, users could buy Amazon and Netflix vouchers,” he recounts. Within a year, the core business got muddled. Oye Rickshaw was all over the place. “We lost focus, got into many unrelated things, and forgot what our main business was,” rues Sharma. Business, he explains, should be like Maggi noodles: Consumers are buying Maggi, not noodles.

First Published: Dec 31, 2020, 14:34

Subscribe Now