Rakesh Tandon: Steering the Resurgence of IRCTC

IRCTC was staring at imminent failure two years ago. Today, it is the largest e-commerce portal in Asia Pacific. Because Rakesh Tandon refused to give up

Award: Best CEO - Public Sector

Rakesh Tandon

Chairman & MD, IRCTC

Age: 58

Interests outside of work: Reading a variety of books, yoga, walking, listening to Indian classical music and playing badminton.

Why he won this award: For fighting the odds and bringing IRCTC back from the brink, and taking his team along with him by encouraging them to take ownership.

Rakesh Tandon’s simple sartorial choices and his calm, restrained manner of speech are deceptive. They cloak a decidedly dogged and combative nature that has been a long-standing asset for the chairman and managing director of IRCTC (the Indian Railway Catering and Tourism Corporation).

You can even trace it back to when he first took his civil services examination in 1976 he scored just 13 out of 150 marks in the essay paper. Disappointed, he worked towards fixing the problem areas in his writing. Tandon got 75 in his next attempt.

This determination has been a hallmark of the 58-year-old’s leadership style, one that has extricated IRCTC from a certain fall into failure a couple of years ago.

IRCTC, started in 1999 after years of deliberation, was meant to keep customer service verticals such as catering, ticketing and tourism away from typical government intervention in order to improve operational efficiency and passenger experience. These had to be run like a commercial business enterprise, not a loss-making social welfare scheme. Despite opposition, IRCTC, for a while at least, made creditable progress, introducing e-ticketing as well as more professional catering services. But things changed dramatically in May 2009, when Mamata Banerjee took charge as railway minister.

Going Off-Track

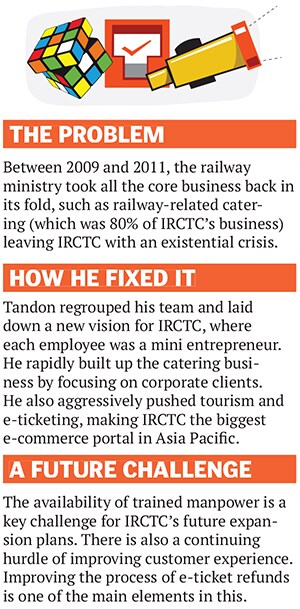

Between May 2009 and April 2011, the railway ministry announced a slew of measures that struck at the core of IRCTC’s business model. In these situations, 99 times out of 100, you would expect a PSU to give up and die. But, under Tandon’s leadership, IRCTC not only survived a near-death blow, but is now scripting a glorious comeback.

Tandon, a 1978 batch officer of the Railway Traffic Service, joined IRCTC as chairman and managing director in January 2009. But he had stepped onto a tough battleground: Not everyone wanted IRCTC to continue. Reason: Catering, e-ticketing and tourism were being managed differently, disrupting the long-standing, inefficient handling under direct government control.

For example, earlier, catering shops at railway stations would be passed on as legacy from one generation to another. IRCTC changed that practice and started allotting shops through open bidding. This way, it ended up realising 50, or even 100, times the reserve price.

In May 2009, however, Banerjee decided to reclaim the catering business for the railway ministry. Catering accounted for 80 percent of IRCTC’s revenues in one fell swoop, its viability as an organisation was severely damaged. Worse, the new catering policy of 2010 took contractual catering away from IRCTC, leaving behind departmentally-run, loss-making units, which had a turnover of Rs 200 crore but were also responsible for almost all the catering losses.

The professed rationale behind these measures was that IRCTC had not lived up to expectations. But observers and even railway ministry insiders felt this was a case of throwing the baby with the bath water. Steps could have been taken to help improve IRCTC’s delivery.

Subsequently, many officials who had left the Railways to join IRCTC decided to go back to the parent cadre. Several others quit altogether. Perhaps the worst affected were the young recruits from leading institutions in the hospitality industry, who were stuck without options.

As for IRCTC, by the end of financial year 2010-11, profitable business worth about Rs 400 crore (from a total turnover of Rs 760 crore) had gone back to Indian Railways. Catering on trains and platform stalls comprised a bulk of the lost revenue.

To offset these problems, Tandon decided to ramp up IRCTC’s e-ticketing capabilities. But, in 2011, he was told that even that service would be provided directly by the government. A commercial portal for freight-related e-ticketing, announced in 2007, was to be the vehicle for Indian Railways. It would charge Rs 5 as service fee as against IRCTC’s Rs 10.

While a relatively smaller component of IRCTC’s overall revenues, e-ticketing was easily the most profitable one. Surely there was no way back now.

THE FIGHTBACK

But, somewhere along the line, the Railways had bitten off more than it could chew. That provided Tandon and his team with an opening to stage their big comeback.

In July 2011, the Railways’ e-ticketing portal, which was launched in Kolkata, shut down after a run of just 20 days it had been unable to handle the traffic. In fact, according to some reports, even when tickets worth a few crores were sold, the money was not realised by a system beset with bungling and mismanagement.

The mandate returned to IRCTC—a crucial first step to regain its footing. Tandon admits that had e-ticketing also been taken away, IRCTC would have been history.

Since taking over in January 2009, Tandon had seen IRCTC getting rapidly undermined. He would stay up till late in the night, worrying about its future. But it is not his style to give up, nor does he believe in leaving the system. “I believe it is better to stay within the system and fight. If you go out, you can only make some noise but real change comes from within,” he says.

The turning point was just around the corner. “I woke up at 2 am one day and jotted down a few key points that I wanted to share with the team,” he says. Later that day, he addressed his team, especially the young recruits. He told them that while it was easy to go back to the parent organisation, he would fight tooth and nail to regroup IRCTC if they were willing to fight alongside him. “The key for me was the enthusiastic response I received from the younger lot,” he says.

Then Tandon laid down the ground rules. Each member had to think of himself or herself as a “mini entrepreneur”. They could no longer look at this as a “10-to-5 job”. “The way to turn profitable at the macro level was to ensure that each unit is run as efficiently as possible so that we make each activity profitable at the micro level,” he says.His first move was to aggressively push to expand IRCTC’s catering business in the corporate world. Today, customers include corporate offices such as HCL as well as several management institutes. He also started providing housekeeping services.

The strategy was to forge partnerships at the local level. IRCTC supplied the brand, the front-end interaction and the billing but the actual work was largely outsourced. He backed such outsourcing with close monitoring to ensure quality.

Later, ironically, as the number of trains grew, the Railways found it difficult to provide catering for them. It turned to IRCTC that now services several new trains, including all the Duronto Expresses.

In just two years, then, Tandon has rebuilt the catering business to the scale where it was at the end of financial year 2010-11. But while catering brings in the most revenue, profits are reeled in by the e-ticketing and tourism businesses.

Today, IRCTC sells 4.7 lakh tickets a day on an average. In 2008, it was just 40,000. The figure will go up by another 50,000 over the next year. Add to this the tourism business, which accounts for 25 percent of total revenues, the same proportion as e-ticketing, and IRCTC generates a daily business of Rs 50 crore. This makes it the biggest e-commerce portal in the Asia Pacific region.

At a turnover of Rs 704 crore in FY13, IRCTC is back to where it was in 2011 (Rs 760 crore). What is remarkable is that Tandon has achieved these numbers without a bulk of the railway catering business, which is valued at Rs 400 crore.

Nalin Shinghal, currently CMD of Central Electronics Limited, worked as director-tourism at IRCTC between 2009 and 2012. “He [Tandon] led the fight very well and on all fronts. He was very supportive of his team and had the ability to delegate—something that not many leaders are able to do,” Shinghal says about his stint under Tandon. As for the never-say-die spirit of the IRCTC team during the setbacks, he says: “It was as if the owner of the shop [the Railways] wanted to shut it down but the shop floor guys were determined to run it well!”

GOING THE DISTANCE

Tandon has only one more year left at the helm of IRCTC but he continues to push growth through innovation. For instance, he is trying to reduce the transaction time for online reservations by starting an e-wallet type service where you can store a certain amount of money with IRCTC.

Similarly, he has brought ISO certification into IRCTC tourism packages with payment to some service providers linked to the feedback from customers. He is aggressively signing MoUs with state governments and their tourism departments to expand the coverage of rail-based tourism.

On the catering front, IRCTC has recently started a state-of-the-art centralised kitchen in Noida, which can produce 25,000 meals daily. The idea is to have better control over the quality of food.

Previous innovations include green tickets (or SMS tickets) which today save 1.5 lakh pages every day. It took Tandon two-and-a-half years to convince the government to give this facility—which air travel started using only a few months ago—the green signal.

Tandon had struck upon the idea of green tickets in unusual circumstances. While travelling from Dehradun to Delhi by train, he had a young techie from Bangalore occupying the berth facing him. When the ticket collector made his rounds, Tandon saw the techie quietly paying Rs 50, the fine at the time for not carrying a printed copy of the e-ticket. When asked, the techie explained his choice of paying the fine instead of taking a printout: He called the process a headache in any case, what purpose did the printout serve?

Tandon was taken aback, and came to the conclusion that asking for paper proof of the ticket, or penalising people for not carrying one, was unnecessary—identity proof should be enough. The government had serious security concerns about this scheme. Tandon eventually suggested a three-month pilot on two trains he also assumed responsibility for any negative fallout. And that’s how green ticketing started in India.

But more than any specific initiative, Tandon’s ability to lead an organisation in the public sector—which is usually not attuned to entrepreneurial zeal—out of crisis has been extraordinary. Even more noteworthy is his humility despite such achievement. “After all,” he says, “working in Indian Railways has prepared me for crisis management because it has a crisis almost every day. I always say: The army goes to war just once but the Railways goes to war every day.”

First Published: Oct 24, 2013, 06:51

Subscribe Now