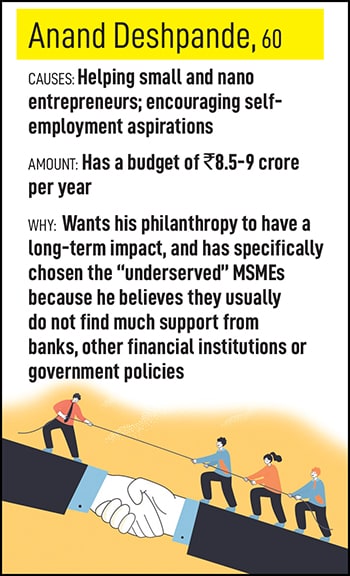

Deshpande speaks a lot about creating “long-term impact" during our hour-long conversation. Like many first-generation entrepreneurs, he spent a good part of his life—over two decades, in this case—to build his business. He is the founder of Pune-based Persistent Systems, a software company he started in 1990 with his savings, and borrowings from friends and family. It provides digital engineering, and data and artificial intelligence products to the IT, banking, health care and financial services sectors. As of February 20, Forbes estimates his real-time net worth to be $1.4 billion.

Through these years, Deshpande had been donating some money here and there, apart from the mandatory corporate social responsibility (CSR) donations that he executed through the Persistent Foundation, but the decision to do something more significant with his personal wealth came around 2013, with the realisation that he had earned sufficiently and should rather use the rest of the money for good instead of keeping it for the next generation.

This led to the birth of the deAsra Foundation, a non-profit that Deshpande launched with a specific focus of using his personal money to support nano and small entrepreneurs in India. According to him, creating jobs at scale is one of the biggest problems in need of attention.

The unemployment rate in India on February 15, on a 30-day moving average, stood at 7.8 percent, with rural unemployment at 7.6 percent and urban unemployment at 8.2 percent, as per data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE). This is a fall from the unemployment rate of 8.3 percent in December 2022. The falling unemployment rate is not necessarily a source of comfort, says CEO Mahesh Vyas in a February 6 note on the CMIE website. “It reflects a falling labour participation rate."

Deshpande believes we need to create millions of jobs every year, and many of these jobs will not come through government or large private companies, but by self-employment. “Everyone accepts that most of India’s jobs are going to happen in small industries, small companies, self-employment etc," he says.

Through deAsra, therefore, he set out to create a repository of all the information people will need in order to be nano entrepreneurs. The ventures they support are typically between ₹5 lakh and ₹1 crore. He feels a business of ₹5-10 lakh at the least is necessary for creating quality jobs with decent income levels.

According to the 2022 annual report of the ministry of micro, small and medium enterprises (MSME), the micro sector with 630.52 lakh estimated enterprises provided employment to 1,076.19 lakh persons, which in turn accounts for around 97 percent of the total employment in the MSME sector.

“This market is underserved," Deshpande says, explaining that people in nano and micro enterprises struggle to succeed, as government policies typically look at SMEs with larger revenues up to ₹250 crore (turnover), and banks and financial institutions also do not easily support this group.

Revati Patil is one such solo entrepreneur who runs Sparkle Bakerss in Pune. An MCom graduate, she used to work as an accountant but always desired to set up her own business. She was weighed down by domestic responsibilities, so started a small bakery service from home in 2015. But the number of her customers were severely limited, so she decided to take the plunge. She rented a space below her home and started a small commercial setup. Orders started trickling in from individuals and small hotels through word-of-mouth.

She learnt about deAsra from a friend and contacted them to understand how to market herself to corporates. “I get orders from individuals and local hotels, but I wanted to cater to corporates, who place orders for celebration cakes and large parties," says Patil, 43, who employs five people in her bakery. “But big companies do not entertain me, and it was difficult to reach them." She is now part of the deAsra network, where she gets access to expert consultations, market linkages and social media management.

![]() Deshpande says being new to philanthropy means spending a lot of time to understand what you want to do, and constantly experiment. “It took us many iterations to get to the point where we are today, which is Version 3.0. I’m not saying we are there yet, and we will never be perfect. We have to keep learning and building on this. It takes time."

Deshpande says being new to philanthropy means spending a lot of time to understand what you want to do, and constantly experiment. “It took us many iterations to get to the point where we are today, which is Version 3.0. I’m not saying we are there yet, and we will never be perfect. We have to keep learning and building on this. It takes time."

The ‘Version 1.0’ of deAsra was a “business in a box", where they created an online kit containing all the information people could possibly need before starting a business. But they soon realised that nano entrepreneurs do not have detailed plans, and nobody took a course or a kit before starting to run a business. So, the ‘Version 2.0’ of the non-profit was to identify the 75 to 80 activities usually carried out by these businesses—like loans, compliance, licenses, market linkages etc—and help them with those.

This made way for the current ‘Version 3.0’, which Deshpande says follows a more structured “seed, soil and surround" approach. Here, ‘soil’ refers to the 75-80-odd offerings with which deAsra helps entrepreneurs. The seed stage comes before that, where they co-create programmes in colleges on how to manage money, create a sales plan etc. This knowledge, Deshpande hopes, will give more confidence for youngsters wanting to start up.

“On the ‘surround’ side, we are trying to see how we can influence policy and think tanks, so they can support these nano entrepreneurs," he explains. The latter entails a deAsra Centre for Nano Entrepreneurship at the Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics in Pune, which can conduct research that can then help guide policymaking.

![]() A business owner at the home and fashion accessories exhibition organised by the deAsra Foundation in association with Grahak Peth, Pune, in July 2022

A business owner at the home and fashion accessories exhibition organised by the deAsra Foundation in association with Grahak Peth, Pune, in July 2022

As of January, cumulatively, the deAsra platform registered over 222,000 first-time users, out of which repeat users were more than 107,000, says Ashish Pandit, who is the head of operations. The organisation says it has delivered over 413,000 services, including “group expert consultation, marketing expert consultations, Udyam registration, business planning checklists, FSSIA registrations and social media services," he adds. Food, fashion and beauty are the most popular sectors, and most entrepreneurs are in the age group of 21 to 30.

They also run an online magazine called Yashaswi Udyojak where they feature success stories and tips by small business owners. They also have sections where people can get their queries answered by Deshpande and other mentors, says Pradnya Godbole, CEO, deAsra Foundation. The magazine is available in English, Hindi and Marathi, and reaches over 42,000 people through various channels. It also publishes business listings, which are popular among their businesses, Pandit says.

The major source of revenue for the non-profit comes from Deshpande’s own money. “Right now, I am not looking to ask anyone else for donations. I know I can afford it, and this way, we have better control over what we do. All our mistakes are our own and I am responsible for them," Deshpande says.

![]()

He says salaries for the 40-odd people employed at the foundation come to about ₹60 lakh per month. The money set aside for the centre at the Gokhale Institute is ₹1 crore a year. “Broadly, I budget ₹8.5-9 crore a year," Deshpande says.

The non-profit also earns revenue from operations, where it charges a fee to provide certain specialised services like social media strategies, assistance with licences, or workshops and boot-camps. For example, Patil, the owner of Sparkle Bakerss, tells Forbes India she pays ₹10,000 per year to be a part of a networking platform that helps her meet other businesspeople and potential clients.

She says she doesn’t mind making the investment, because she knows first-hand the lack of a support system out there for female entrepreneurs running small businesses. “During the pandemic, I came very close to shutting shop, but I kept going. Even today I do the bulk of the housework, but my business is my dream and my purpose. To keep it alive, I need to keep building on my knowledge, and learn how to save, scale and look for opportunities to grow my business. Being part of the network will help me with all that," Patil says, adding that her goal is to open two more outlets in Pune in the next six months.

Deshpande explains that small and nano entrepreneurs are not always willing to pay for such services. And most are often suspicious about being tracked or their data being misused. “We do not insist on them reporting anything or sharing financials… nor do we collect any data from them," Deshpande says. But they are moving towards creating a subscription model in exchange for a bouquet of services, he explains, as that would give the organisation an additional revenue stream to help it sustain over the longer term.

Right now, Godbole says, 50 percent of their entrepreneurs are from Maharashtra, and the rest are from urban and semi-urban areas pan-India. To further tap into rural areas, Deshpande is forging partnerships with local organisations with a strong grassroots presence. Over the years, some of their partners, as per the deAsra website, have been the National Skill Development Corporation, Pratham, Global Alliance for Mass Entrepreneursip, GMR’s Varalakshmi Foundation, and the Swavalambi Bharat Abhiyan (SBA).

“Anand Deshpande is a simple, down-to-earth person. He and his team are always accessible and ready to collaborate," says Archana Meena from the SBA. The organisation, which is an initiative by the Swadeshi Jagran Manch that is affiliated with the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, is using its national grassroots network to connect 100 small entrepreneurs in need of help to deAsra. “He [Deshpande] is passionate about giving back to society, about helping small entrepreneurs dream big, which is worthy of praise."

Deshpande says being new to philanthropy means spending a lot of time to understand what you want to do, and constantly experiment. “It took us many iterations to get to the point where we are today, which is Version 3.0. I’m not saying we are there yet, and we will never be perfect. We have to keep learning and building on this. It takes time."

Deshpande says being new to philanthropy means spending a lot of time to understand what you want to do, and constantly experiment. “It took us many iterations to get to the point where we are today, which is Version 3.0. I’m not saying we are there yet, and we will never be perfect. We have to keep learning and building on this. It takes time."