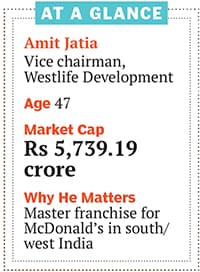

Amit Jatia and McDonald's 15-year Wait for Success

Amit Jatia and McDonald's stuck by each other and adapted to value-conscious, vegetarian India. After 15 meagre years, they're finally feasting

“When I got back and got into the chemical business, which was a US collaboration, I could connect well with my American colleagues,” says Jatia, 47 (net worth $665 million). He spent three months in the partner’s plant in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, to learn the American way of working. He says in America it’s about simplicity in India it’s all about complexity. And it doesn’t get more complex than India’s labyrinthine red-tape. Navigating the American partners through the Indian quagmire couldn’t have prepared him better for what came next.

In 1994, McDonald’s—perhaps America’s most visible export—called, and Jatia jumped at the chance. On March 1, 1995, he became their local partner in south and west India through a 50:50 joint venture between his Hardcastle Restaurants and McDonald’s. In December 2010, Jatia bought out McDonald’s stake in the south and west joint ventures, and Hardcastle was merged with the Bombay Stock Exchange-listed Westlife Development. Jatia is now running McDonald’s India’s venture in the south and west.

(For north and east, McDonald’s entered a similar 50:50 JV with Vikram Bakshi’s Connaught Plaza. In August 2013, McDonald’s ousted Bakshi as MD of Connaught Plaza and instituted two members on its four-member board. McDonald’s Asia is running McDonald’s India’s ventures in the north and east. Bakshi is trying to buy out McDonald’s stake, like Jatia did, but is in a legal battle.)

After buying out McDonald’s stake in the JV, Westlife’s stock shot up and even though same-store sales are down 10 percent year-on-year (competitors like KFC, Dominos are experiencing similar slowdowns), revenues are up 4 percent to Rs 179 crore.

Jatia has grown McDonald’s to over 183 outlets across 18 cities: After struggling for 15 years, he began to make profits in 2009 and has ridden India’s QSR (quick service restaurant) boom ever since. With a steady cash profit and public funds, Jatia is looking to open 40 stores a year till 2019.

A Family At Work

While wife Smita works with him at McDonald’s, his twin sons are studying at NYU. Jatia’s father, grandmother and younger brother Achal’s family also live in their Breach Candy home in Mumbai. Achal runs the lubricant business while youngest brother, Anurag, lives in Hong Kong. Every morning the brothers catch up over tea and heed their father’s words of caution. “Whenever he sees me going off track, he’ll tell me,” says Amit, who is in a strong position because he stayed the course during tough times.

It was only after McDonald’s cracked the ‘value play’ around 2002 that things began to look up. “McDonald’s told us if you don’t have a 10- to 12-year view, this is not the business for you,” he says. “Luckily our family background helped, because in industry it’s the same thing.”

The Jatias, originally from Bissau in the Jhunjhunu district of Rajasthan, now have a conglomerate comprising paper, textiles, real estate and chemicals, along with restaurants. In the 1950s, while based in Burma, they established bases in Japan and Hong Kong. In the ’60s, one part of the family moved to Mumbai and started trading in textiles and chemicals. In 1970 they acquired Pudumjee Pulp & Paper Mills, a small but efficient mill in Pune. “That was our move into industry,” says Jatia. “From the ’70s until we separated in 1992, Pudumjee became one of the best paper mills in the country. Even today it’s the only company that does tissue paper.” Then they acquired Hardcastle (a board manufacturing company), Modern Mills (a textile mill in Mumbai), Associated Stone Industries and so on. That, he says, is how the Jatias transformed from a solid, low-profile family into a diversified conglomerate.

In 1987, after he graduated from USC, the family had just established a joint venture with an American company for specialty lubricants. Asked whether he wanted to live off-shore and run the trading business or return and work on this, he made it clear it was always about coming to India and manufacturing. “I couldn’t think of anything but manufacturing!” he says. “When I understood the product lines in the lubricants business, I said nobody in India is going to pay for safety!” says Jatia.

“Yet, as I dug deeper, I found it to be a gold mine. It was new-age technology in a very traditional industry. When the group separated in 1992, coincidentally that was the business that came to my father.” The Jatias were looking to make more investments because from being present in various industries, they found themselves only in the chemicals business. That’s when McDonald’s came knocking.

A Taste of something different

The first time he tried McDonald’s was in Japan, when he was 14 or 15. He loved the milkshakes—being vegetarian he couldn’t have much else. “I figured out fries only when I went for my education in the US!” he says.

Convincing his family to open a burger joint wasn’t going to be easy. “This was April 1994. We are a vegetarian family and my first reaction was that it won’t work,” says Jatia. “In August they [McDonald’s] came down and met me and then again in October. I discussed this internally in the family. My cousins were running the Hyatt in Delhi. I told my dad, ‘At the end of the day I’m not changing my beliefs and we’re only serving meat to people who eat it. There’s no beef or pork and they’re willing to do separate kitchens, vegetarian products, etc… So how does it matter?’” Jatia Senior said OK. “For a vegetarian, sometimes the smell of meat and fish can really psyche you, so I worked in a McDonald’s kitchen for three days in Singapore.” Whoever joins McDonald’s, regardless of seniority, has to spend a few days in the kitchen.

It turned out that adapting to the vegetarian needs of the family was a marker: McDonald’s has consistently Indianised its menu for value-conscious, veg/non-veg customers to great success. As early as 1997, it introduced Aloo Tiki. Then came Pizza Puff, McGrill and so on. In India, it’s an even 50:50 split between veg and non-veg sales, though each market has its skew: In Gujarat it’s towards veg, in Hyderabad it’s towards meat. Every outlet’s kitchen is split veg/non-veg, right up to the plant. “It cost me a lot of money! We have two production lines if I could use the same line, I’d save half the cost.” But they felt it made more sense to build trust around veg/non-veg segregation than do veggie-only restaurants because it splits customer groups. Even in his extended family, not everybody is vegetarian. “When we go out for dinner, my uncles want meat!”

Cracking the Business Model

The business model had to be changed for India: There were more people visiting the restaurant, but the average spend was very low and the cost structure didn’t make sense. They started with a local supply chain, which was a big drag on profits. Establishing cold chains and transport networks weren’t cheap. “You don’t invest Rs 500 crore for 20 restaurants—it’s done for 200 restaurants and it’s taken us 10 years to get there,” says Jatia. “When the plant cost was 100, we couldn’t charge the customer 100. We were charging 70 or 80 while our cost structure was 100. But as we kept opening stores, business costs kept coming down and margins went up. As late as 2009 they crossed over.”

He got the cost structure right by 2002. The goal was for every new McDonald’s to make money on its own account. McDonald’s did this by localising the fabrication and equipment, bringing down building cost by 50 percent. According to their research, in 2003, of 100 meals that people ate in a month, only three were eaten out. That’s when the Rs 20 menu came in. The objective: Take the three meals to five, and seven and 10. Jatia says that’s when we introduced ‘value’. “Once we got the Happy Price Menu in, the frequency in Mumbai went from three to eight,” he says.

One cannot visit the McDonald’s story in India without addressing the issue of ownership and the looming spectre of legal battles with Vikram Bakshi. But Jatia is unfazed. “McDonald’s believes that different ownership structures work for different stages of development. At the early stage it’s about handholding the new partner. They’ve been tremendously supportive,” he says. For India, for the last 15 years, every penny of royalty has been ploughed back into marketing—only recently did they even think about taking their dollars back. This concept of re-investing in the business is something he’d also seen his family do. “When [McDonald’s] found business was getting better in 2009, they felt the correct ownership structure was to make us a licensee. And they’ve done that around the world [going from JV to full licensee],” says Jatia.

Abneesh Roy, associate director, Institutional Equities Research at Edelweiss, says Westlife’s recent stock valuation is because of the McDonald’s India business reflecting clearly in Westlife—it simply wasn’t so under the previous fragmented model of separate JVs. “Globally it doesn’t allow a local listing,” says Roy. “India is just the second example, apart from Brazil. That shows Jatia’s working relationships.” He explains that same-store sales are an important metric in assessing QSR chains because they generate profitability: McDonald’s has fallen 10 percent, compared to rivals Dominos’ 3 percent fall and KFC & Pizza Hut’s 4 percent fall. But Jatia likes competition. If customers get more, the category grows, he says. “If there’s a McDonald’s and a KFC and a Pizza Hut and a Dominos in a single location, everybody does well.”

Jatia sees the slowdown as a time for examining efficiency. Take development cost: They still import high-tech kitchen components, and though the dollar went up to 62, they managed to keep development cost constant. “We worked with new manufacturers in India. If I can build a Mercedes and a missile in India, why can’t I do fryers and grills?” On the front end, the McCafes (coffee-house-style outlets recently launched in India) create different segments in a day that aren’t usually that busy while lunch and dinner are typically what you see at a restaurant, McCafes are helping create breakfast and coffee times. Margins are also better on beverages.

“For me to slow down my growth just because current sentiment is down, doesn’t make sense,” Jatia says. “It’s like when you’re on a flight and you save an hour when the wind is in your favour: I want to keep myself light so that when the wind changes, we can go further than anyone else.”

These fundamentals came from watching his father do business: “We are a very focussed family. Even through the most difficult years, we never did 10,000 things. We could have easily said hedge your bets because there were rough phases as we were building the McDonald’s business. My father’s philosophy is: Do a few things well.”

First Published: Mar 13, 2014, 06:02

Subscribe Now