Maharashtra Drought: The Worst Man-Made Disaster in Years

A callous polity and years of poor governance has brought about a major man-made disaster in Maharashtra, which is set to turn worse in the coming months

The usual dusty small-town India greets us as a small group of people associated with the NGO Caring Friends travel over two-and-a-half days through Aurangabad and Jalna to understand the problems in the region and what help could be given. On the face of it, people seem to be going about their normal life. Where are the signs of distress that we had read in the media? Don’t girls and women in many parts of rural India carry water over long distances? Aren’t water tankers a common sight in many towns and cities, including Mumbai?

The feeling that all is normal is broken the moment we see the dried up, shrivelled fields of sweet lime (mausambi) and cotton planted on thousands of acres along the way. When we stop to speak to people, the consensus is that this year’s drought is worse than the one in 1972. But there is one major difference: There is no shortage of food this time around. Although we hear stories of cattle perishing and migration out of villages in search of work, fodder prices have remained remarkably stable.

However, the price of one commodity has moved up: Water, usually considered to be available freely like air. One tanker of water (8,000 litres) now costs Rs 1,200-1,500, up from Rs 300-500 last year. Increasingly the tankers have to fetch water from places further away. We hear numerous stories about how ground water is depleting fast: In Sangli, some 20,000 bore wells were dug over two months, all up to a depth of 600-1,000 feet and water was found in less than 50 bore wells we hear about “Bore Bahadur”, a person who dug 41 bore wells in an acre of land in Amravati district.

One of the most heart rending stories for me is to know that girls in a local college hostel were eating just one meal a day to save on costs because otherwise their families would have pulled them out of college. Girls are the first to be pulled out when resources are stretched and extra hands are needed to fetch water. The Chamber of Marathwada Industries & Agriculture has started giving scholarship of Rs 1,000 per month to the girls so they can eat two meals a day and continue their education.

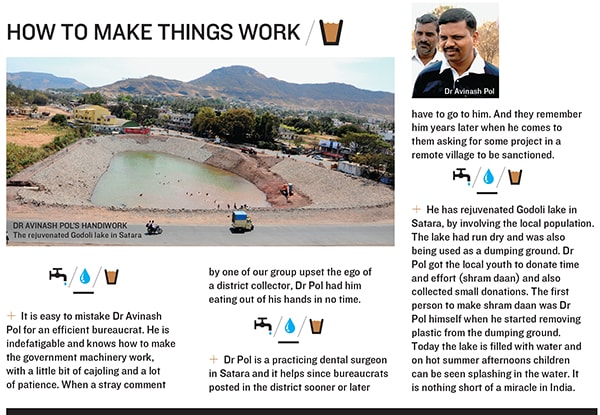

Our first stop is village Vadkha, in Aurangabad district, where Dr Avinash Pol of Satara has been helping people to build check dams. Dr Pol is a dental surgeon, but for the people in Satara district he may well be a superhero. He has rejuvenated lakes and ponds, got government schemes sanctioned and implemented, something which we all know is near impossible.

Vadkha is just another dot on the map, less than an hour from Aurangabad. Right next to the village primary school is the only well in the village where women and young girls are drawing water. Vadkha is a well-to-do village by all accounts every day two tankers come and pour water into the well. The tankers cannot wait since they are in great demand and more trips mean more profits.

A special mid-day meal is being prepared in the primary school, as a farewell to the Class VII students who will now head out to the nearest secondary school. The men and teenage boys languidly mill around the village square. I am left wondering why the young girls are not in the school, and are drawing water instead. Is this India’s demographic dividend?

The drought has been a boon for village stores where Nestle’s Dairy Milk Whitener is doing brisk business, as milk supplies in the village dry up.

Consumption is booming if you go by the motorcycles and the products being sold in the shops.

The blackened trees with shrivelled fruits, some still a dark shade of orange, is the first sight that tells us all is not well. Lakshman, a young farmer from Akoladev village, has formed a co-operative of farmers with 2,500 acres of fruit and cotton cultivation. Almost 90 percent, he reckons, has been lost. We are standing in one of his farms and all the sweet lime trees are brown and dead. The earth is parched and cracked. He’s paid back the Rs 8 lakh loan he took when the limes were planted the trees have a normal fruit bearing life of 15 years, but they’re all dead in five. As I stand there taking pictures on my camera, a villager accompanying us is also taking some on his camera. Both of us are Nikon users—a D80 for me and a Coolpix for him.

About 30 km from Lakshman’s village is a huge man-made lake—rather, it used to be a lake, we were told. Up from the embankment, about 30-40 feet high, what we see is not a lake but a huge field of melons. The melon plants are withering away and most of the tiny melons have started rotting for want of water. Villagers have dug two wells and are laying a pipeline to the nearest well where there is a pumping station to pump water to their village. All this is being done at their own cost (about Rs 2.5 lakh plus the labour they are putting in), whereas it costs Rs 3 lakh per month to get tankers to supply water to the village (assuming per capita per day consumption of 3 litres, in the village of over 4,200 people). The government prefers to supply tankers water rather than build pipelines.

By the time we walk down to the newly dug wells, the pipeline is ready. Dr Pol presses the switch to inaugurate the pipeline and by the time we drive down to Akoladev, there is water in the village taps. The water from the well is muddy brown. Nimesh Sumati, co-founder of Caring Friends, is carrying samples of ‘Life Straw’ water filters, which do not need power and are easy to use.

Lakshman and the others around him are not broken. They can still smile. This is the clichéd and much abused resilience of the people. People in Mumbai, London and New York exhibit it when under terror attack, people in Akoladev exhibit it when they are reeling under drought.

The poor are perhaps resilient also because of the extremely difficult conditions and uncertainty they live with. The drought only makes it a little worse. Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo in their book Poor Economics, while discussing the impact of the 1998 financial crisis on the poor in Thailand write, “For the most part, it seems that, once again, things were not a lot worse for the poor than in any other year, precisely because their situation is always rather bad… For the poor, every year feels like being in the middle of a colossal financial crisis.”

The previous evening in a meeting organised by the Rotary International group in Jalna, one felt that the local businessmen were more depressed than the poor villagers. For the businessmen this was new. They also had better appreciation of the tragedy unfolding and the implications going forward. This is only March and the next two months are going to be very painful. Around Jalna is a thriving steel rerolling industry that employs 35,000-40,000 people in a town of nearly 400,000, and accounts for 35-40 percent of Jalna’s economy. This industry is water intensive and as it continues to buy water, the price of water tankers is going up. If the mills stop, thousands will be out of jobs. Talk about the devil and the deep sea.

From the media reports that I’ve read, it seems that the drought is the result of poor monsoons this year. But a few hours into our visit, it is evident that this is not due to poor monsoons. It is a colossal man-made disaster stemming from poor governance over decades. Ghanewadi, 8 km from Jalna, is our first stop en route to Jalna. This used to be a man-made lake spread across 657 acres, built in the 1930s when Jalna used to be a part of the Nizam’s Hyderabad Estate. This is, or rather used to be, the primary water source for the town of Jalna and water used to flow by gravity to the town.

When we visit the site, it is difficult to visualise a lake. Two excavators are working on the site. The lake has not been desilted for decades. As a result, all the rain water was being lost. This also meant ground water recharging was not happening. From 2010 onwards, Rotary International of Jalna started using its resources to desilt the lake, but their efforts are not enough. They are spending about Rs 25 lakh every year. The farmers from nearby villages spend an equivalent amount to collect the top soil which is very fertile. There has been absolutely no assistance from the government yet. During our visit, the local administration promised the diesel required for the excavators to work till the monsoon came.

Our next stop is a river that runs through the centre of the town. Or what used to be a river. Today it is a river of debris and plastic it is the dumping ground for the town. I read the next day in the newspaper that the mighty Yamuna has zero oxygen content as it reaches Delhi and is clinically dead. The river in Jalna has long been dead. Jalna’s problems are not unique in India, but a dry region exacerbates the issue.

Most of us will find it difficult to even imagine it, but the 400,000 inhabitants of Jalna do not get water in their taps for even a single day in the month. They buy water almost every day. The problem has worsened over the years, and this is the new normal now. Who benefits from this lack of governance? The local politicians who run all the tanker business. The poor who cannot afford to buy a full tanker load and buy a fraction, end up paying more—they end up paying a premium for being poor.

What is the government doing? The day we landed in Aurangabad, the Centre sanctioned a drought relief package of slightly over Rs 1,200 crore for Maharashtra the state government has waived off a long pending bill of Rs 36 crore that the Jalna Municipal Corporation (JMC) owes to the Maharashtra State Electricity Distribution Company (MSEDCL). JMC would now be able to pay for power and this would pave the way for pumping water over a distance of about 100 km (88 km according to some news reports) from the newly built pipeline from Jayakwadi dam.

Wouldn’t this solve Jalna’s problems? From bureaucrats to social workers to industrialists to the poor farmer—all say in one voice that the government’s plans are ill conceived. The 88 km pipeline has been built at a cost of Rs 250 crore. The monthly electricity bill is estimated to be about Rs 30-35 lakh and JMC cannot afford to pay that bill. It simply doesn’t have the resources. So what is the rationale for building this pipeline? We were told that some politician from the ruling dispensation in Maharashtra has a sugar plant on the way and would draw water from this pipeline. In the name of 400,000 residents of Jalna, Rs 250 crore is being spent for the huge benefit of a sugar baron-cum-politician. At a fraction of that cost, Ghanewadi and other lakes in the region can be rejuvenated and villages and towns can be made drought-proof.

The governance issue does not end there. Our group discusses with a senior bureaucrat on how we can help. This bureaucrat has a huge reputation of being an honest official. His advice is very clear: He tells us to do whatever we want to do on our own if we want to work with the government, the people will not benefit. Only Rs 10 out of every Rs 100 spent will reach the people. It is anyone’s guess how much of the drought relief sanctioned will reach the people.

As I write this on March 27, I am assailed by the sound of Holi songs wafting in from all around. I love Holi. But my 13-year-old has refused to play this year since his school teacher has asked them not to in solidarity with the unprecedented drought in the state. When I raise this with two friends, they say this is being politically correct and for just one day in the year we can surely play Holi with as much water as we want. Our complex has two tankers that have delivered water for playing Holi.

Meanwhile in Jalna and Aurangabad people are buying tanker water every day for drinking.

Within a week of the first visit, Nimesh Sumati was back again. Helping him is a band of local people and NGOs in the region ranging from Girish Kulkarni of Snehalaya, Neelima Mishra of Bhagini Nivedita Gramin Vigyan Niketan, Dr Avinash Pol, Dr Avinash Sao of Prayas and Madhukar Dhas of Dilasa, among others.

After his second visit, Nimesh wrote to me: “In Akoladev, the tank at the village is called Jeev Rekha [lifeline] we have desilted more than 3,000 tractors in 8 days, 3 big machines are at work. Atul has successfully installed a solar pump here, 450 villagers were also enrolled under MNREGA. We have also taken up the work of building a check dam for a nearby village Neemkheda of about 70 families and 100 people from this village were also enrolled under MNREGA, thanks to the contacts of Dr Pol who has also convinced a few senior government engineers to visit this place next weekend. We have installed a drinking water tank at the bus stand which serves 600 litres of water per day, some bowls of water have been hung on trees for the birds and 2 water holes for the larger animals. In all, the above de-silting work would benefit more than 5 villages and 25,000 people.

“In Jalna city, ‘Life Straw’ family filters are installed in the lower income group area, women come with their water, filter it and take it back. This model is working well and we may increase the numbers. We are planning a big shram daan in the last week of April for which we approached Anna Hazare through Girish Kulkarni who knows him well, and he has kindly obliged.”

A foreign correspondent travelling through the drought hit areas of Maharashtra in 1973 wrote, “Maharashtra’s peasants millions have shaken off their apathy and are actively, eagerly working not only to stave off immediate disaster but to transform their blighted landscape into new India. Across the length and breadth of the state literally millions of people are engaged in collective action to build dams, roads, sink wells and reclaim the land.” Not much seems to have changed in the last 40 years. The same peasants and some good men are at work again. Or maybe the work of the good men prevented a crisis over the last 40 years.

Maybe it is the few good men or maybe it is the resilience of the people or maybe god is with this country of ours and that is why, in spite of everything, there is always hope. The first evening at Jalna, as we stepped out to have dinner, the sweet smell of wet earth greeted us. Rain drops were falling and god, it seems, is indeed with India.

Anirudha Dutta is former head of research at CLSA India and blogs at forbesindia.com

First Published: Apr 30, 2013, 06:03

Subscribe Now