Jazz and the art of being South Asian in the US

South Asian-Americans are forging new paths in jazz—and in the immigrant experience

Almost more than any other kind of music, jazz is a union of opposites. Rooted in tradition, it is forward-looking and constantly evolving. It has to come from the soul but speak to the mind. And jazz has long embraced East and West. From the time American jazz bands first visited India in the 1920s to the 1950s and 1960s when Indian musicians went to America—resulting in notable collaborations such as the one between Ravi Shankar and John Coltrane—jazz and traditional Indian music have been in dialogue.

What do they have in common? “Improvisation within structure,” summarises Neelamjit Dhillon, who is a jazz saxophonist and a doctoral candidate in tabla performance at the California Institute for the Arts. Both types of music call for the performer to improvise tunes while staying within the boundaries of a certain rhythm. “The grammar is different but the underlying principles are the same,” Dhillon clarifies.

Musicians who are “fluent” in one of these languages can gain a quick, albeit superficial grasp of how to communicate in the other: One reason that past attempts at fusing Indian classical music with jazz often sounded more mixed than married. (Shakti, a group which brought together English guitarist John McLaughlin, South Indian violinist L Shankar and Zakir Hussain on tabla in the 1970s, is named by most jazz musicians as the exception.)

Today, however, a new generation of desi musicians has emerged who are not only bicultural but musically bilingual. They have been able to integrate jazz and classical Indian music from their own experience of inner “fusion”: Being as American as they are South Asian. And each of them has something different to add.

Vijay Iyer: Shouldering Responsibility

Pianist Vijay Iyer, 43, is probably the most visible member among the group of South Asian-American musicians who have established themselves as leaders in the contemporary jazz world. He began learning the violin at the age of three and pursued degrees in science while also studying piano. He is the recipient of an ever-growing list of awards and honours. Most recently, he was appointed to a professorship at Harvard and named Artist In Residence at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Yet, all the recognition makes him uneasy. Iyer fears that the focus on him as an Indian-American artist is a way to bypass the fact that jazz is “bound to blackness”.

“This is music that came from multiple African-American communities,” he says. “The centrality of rhythm and improvisation comes from African aesthetics, and the conditions people have been subjected to—that’s been part of its identity since the beginning.” He says that in the hundred-plus years since jazz emerged as a fusion of African rhythms with European melodies, it has continued to adapt and change in response to conditions.

According to him, the cities where jazz was played and practiced became like particle accelerators of populations, aiming different groups of people at one another—and impacting the music. Iyer worries that one effect of all that mixing is that the connection to black culture could be lost. “On one hand, we have to adhere to this thing called jazz from someone’s vision of the past, and on the other, we see the music evolve alongside communities,” he says. “What does that have to do with me as a South Asian musician? That is something I am trying to express with music.”

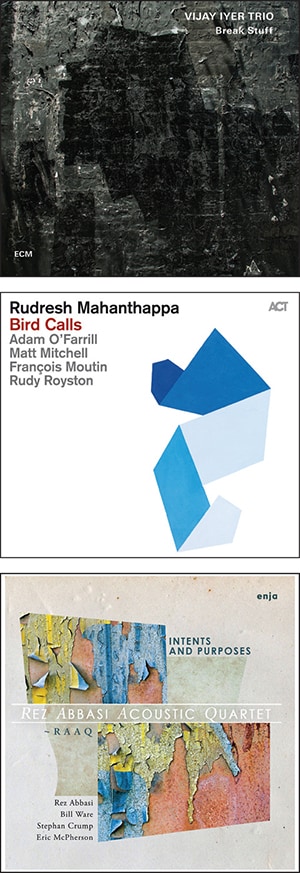

Both the sheer volume of his output and the emotional range of his music reflect the search for a meaningful answer to that question. He has released 20 albums as a leader, mostly with the mainstream jazz Vijay Iyer Trio, whose latest album ‘Break Stuff’ was released in February. He has also spearheaded projects that bring together Indian influences with jazz. Recent examples include ‘Tirtha’, his 2011 recording with tabla player Nitin Mitta and Prasanna on guitar, and the score he composed in 2013 for filmmaker Prashant Bhargava’s Radhe Radhe: Rites of Holi. He collaborates often with other South Asian-American jazz musicians too, notably fellow New Yorkers Rudresh Mahanthappa and Rez Abbasi.

Rudresh Mahanthappa: Following Curiosity

Number theory and cryptography fascinated alto saxophonist Rudresh Mahanthappa from an early age. His 2006 album ‘Codebook’—recorded with Iyer on piano—was an exercise in applying the concepts of encryption to jazz, while his latest, ‘Bird Calls’, scrambles motifs from classic Charlie “Yardbird” Parker tunes with elements of Carnatic music to create a kind of puzzle where listeners can play with the pieces. Mahanthappa, 44, avails himself of the full range of the saxophone, tripping from bass tones to high notes with a high level of energy.

Academically trained in the Western music tradition, he has also spent time in India apprenticing himself to the melodic and rhythmic aspects of Carnatic music in particular. “The greatest way of marrying Indian music and jazz is to break them down to their raw elements because that’s how you’ll get something new,” says Mahanthappa. But when it’s a question of the technicalities of bringing East and West together, “my initial reaction is that the music is secondary,” he says. “It really stems from this experience of figuring out who I am in this country.” In interviews, he has often spoken about the experience of “feeling white” growing up because there were very few other Indian-Americans around. It wasn’t until college that he began to engage with his heritage and weave it into his musical identity. Discovering the commonalities between classical Indian music and jazz, which he describes as “interaction and interplay, a sense of rhythmic propulsion at their core,” has been the code he has worked to crack ever since.

In 2009, Mahanthappa released an album called ‘Kinsmen’, co-led with Carnatic saxophonist Kadri Gopalnath. Other players in the Dakshini Ensemble, the group convened for the project, included violinist A Kanyakumari and Abbasi on the guitar and the hybrid sitar-guitar. Though one of his most successful projects, it posed a major challenge to Mahanthappa. “There’s blues and raga not only at the same time, but simultaneously, and everyone has to be aware of all the parts.” That challenge highlights one of the main differences between jazz and Indian classical music: The latter is entirely based on a standard repertory. “Whereas in jazz, writing your own music is more important—and more prevalent than ever,” he says. Mahanthappa continues to explore different kinds of music besides Indian classical, including contemporary Western classical, rock, singer-songwriter, and even children’s music (thanks to his two-year-old).

Rez Abbasi: Finding Freedom

Rez Abbasi, 49, was a guitarist by the time he was 11, and began playing in garage bands in his early teens. He idolised guitar-heavy rock groups like Rush and Van Halen. At 16, he discovered jazz and the creative possibilities that came with it. “Jazz is a verb, not a noun,” he says. “It’s just music that is calling out for newness, and since it’s an American music, the newness comes from outside America.”

Improvisation is not the only thing that classical Indian music and jazz have in common. It’s also what makes them less commercial forms of music. “It requires active listening and a bit of an educational background in jazz to relate to all the ins and outs of the theory and harmony and all the things we have studied,” Abbasi says. According to the most recent Nielsen SoundScan report on the music industry, jazz tied with Western classical to become the least popular genre of music in America last year, with just 1.4 percent of market share.

What does that say about its future prospects? Abbasi thinks his own experiences and career indicate the direction that jazz is evolving in more broadly. It’s a similar situation to the equally broad label of world music in the way that ethnic tradition, mainstream pop and electronic influences have all begun to merge. Abbasi continues to take inspiration from sources as diverse as Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and Stevie Wonder. “We have people like Rudresh and Vijay and me coming out of the woodwork and doing something that employs their own heritage as well as something that’s very American,” he says. “[But] if I was any other musician than a jazz musician, it would have been a different experience to incorporate some of these elements of our roots.”

Notes on a word

Apart from being a music of paradox, jazz as a term has proved notoriously difficult to define. No one knows where the word first came from. Several of the greatest jazz artists such as Coltrane and Duke Ellington refused to apply it to themselves. In that way, however, it encapsulates the quintessentially American insistence on inventing your own identity. Filmmaker Ken Burns, who made a TV miniseries on jazz that was turned into a book, writes in the preface, “[Jazz] is about immigration and assimilation and feeling dispossessed—and the music that came to the rescue.”

For Iyer, Mahanthappa and Abbasi, jazz has been as much a way to express themselves as artists as to define themselves as individuals. Drawing on both the “repertory” of their ethnic heritage as well as the “swing” of American life, they are continually improvising who they are and what they have to say in their music.

First Published: Jun 22, 2015, 07:21

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Jun 18, 2010 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)