The next stage: The evolving face of theatre in India

Actors, dancers and directors are breaching the barriers of high and low art, drawing from traditional classical performances to tell their stories

In MÄlavikÄgnimitram, one of the first plays he wrote, Sanskrit poet Kalidasa (4th-5th century AD) evoked the sublime power of drama, describing it as a beautiful visual sacrifice for the gods. He ends a shloka with: “Natyam bhinna rucherjanasya bahuopyekam samaradhanam.” This translates to: “Drama is the single (unique) means of pleasing people of different tastes in many ways.” Did the poet realise that his words would resonate with Indian thespians more than 15 centuries later?

Across the country, actors and directors, poets and playwrights, dancers and musicians are finding new ways to tell their stories on stage. And while they may rely on complex light and sound design, props and extravagant backdrops, the power of their theatre remains as pure as it was during Kalidasa’s time: It is cathartic. It is entertaining. And it shines light on topics like gender, sex and oppression.

But theatre was never egalitarian, at least not in its classical avatar. The Natyashastra—a treatise on the performing arts that dates back to 200 BC—differentiates between ‘Margi’ (high art) and ‘Deshi’ (populist, meant for the layperson). Over generations, the lines demarcating the two have blurred, and this convergence, in a sense, is being played out today.

Sanjukta Wagh from Mumbai and Vivek Vijaykumaran from Bengaluru use Kathak and Kutiyattam (traditional dramatic dance).

Others, like Patna’s Randhir Kumar, direct all-male troupes which fall back on the Bihari folk tradition of ‘Launda Naach’, performed by men dressed as women. In Assam, Pabitra Rabha trains dwarves, and in Bihar, Pravin Kumar Gunjan fights caste politics and oppression on stage. They may speak different languages, but they find common ground by challenging their audience to question the world as it is.

In this mix of high art and low art, there is a strong European influence. The roots of mainstream theatre, with its divisions along the lines of ‘acts’ and ‘scenes’, can be traced to the Raj. The second half of the British rule saw the rise of protest theatre when the fight for Independence spilled onto the stage with the Indian People’s Theatre Association (formed during the Quit India Movement in 1942). Independence gave us new confidence. If the government’s setting up of the Sangeet Natak Akademi in 1952 was the foundation of cultural awareness, then it wouldn’t be wrong to say that institutions like the National School of Drama (1959) provided a platform for modern theatre. The period before and immediately after Independence saw the emergence of dramatists, poets, actors and directors like Ebrahim Alkazi and Urdu dramatist Habib Tanvir, Shambhu Mitra, Chandravadan Mehta and Ranchhodbhai Udayram Dave in Gujarat, Gurajada Apparao and Bellary Raghava Chari in Andhra Pradesh, Laxminath Bezbarua in Assam, Kerala’s CV Raman Pillai and Kalicharan Patnaik from Odisha, all of whom were vital to the revival of Indian theatre.

This tradition was carried forward by a host of artistes and writers, including but not limited to Vijay Tendulkar, Girish Karnad, Kanti Madiya, Pravin Joshi, Mahendra Joshi, Shashi Kapoor, Dr Shriram Lagoo, Zohra Sehgal, Farooq Shaikh, Naseeruddin Shah, Amol Palekar, Usha Ganguly, Alyque Padamsee, Sanjana Kapoor and Chetan Datar among others. They’ve laid the ground for a medium that’s trying to hold its own against the likes of reality TV and Bollywood.

Today, artistes and directors are building on this foundation. Our curation is by no means comprehensive, but we have focussed on new entrants as well as old hands who are working in multiple languages across India.

Here are snapshots of creative forces who have stayed unfettered by convention. Image: Rafeeq Elias

Image: Rafeeq Elias

Yuki Ellias (right) in the play It’s Not Waht You Tihnk, directed by Deepal Doshi

YUKI ELLIAS

Troupe: Mindspring, Mumbai

Language: English

For Yuki Ellias, 35, performance is a sport. She practices the craft of theatre through the use of space and the human body, and the interaction between the two. In many ways, the sheer physicality of her productions owes its roots to the time spent working with British theatre director Tim Supple on Indian Dream, his multilingual interpretation of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream where actors performed demanding acrobatics on stage. (Ellias played the role of Hermia.) She has studied at the Jacques Lecoq School for Theatre in Paris and the London International School of Performing Arts. She made her directional debut in 2015 with Charge, an absurd sci-fi comedy.

Vivek Vijaykumaran uses Kutiyattam in his production, Bhima

Vivek Vijaykumaran uses Kutiyattam in his production, Bhima

VIVEK VIJAYKUMARAN

Troupe: Our Theatre, Bengaluru

Language: English, Hindi

Vivek Vijaykumaran, 31, staged his first multilingual production, an adaptation of dramatist Badal Sarkar’s Beyond the Land of Hattamala, in 2009 to excellent reviews. Since then, he has produced Naariyal Paani (a Hindi play about a small-town boy who no one listens to) and Prelude (an English–Hindi play on an individual’s journey from introspection to hypocrisy). His latest production, BhÄ«ma, uses elements of Kutiyattam, an ancient form of dance theatre performed in Kerala. The plot, which draws from the Mahabharata, explores the chasm between expectations and outcomes. An actor from the Raaga troupe in the play Putrid Prologue

An actor from the Raaga troupe in the play Putrid Prologue

RANDHIR KUMAR

Troupe: Raaga, Patna

Language: Hindi, Bhojpuri, Maghi, Maithili and English

Randhir Kumar, 37, an alumnus of the National School of Drama, established Raaga in 2007. Based in Patna, Bihar, the theatre company comprises young thespians, writers, set designers, musicians and artistes. But they are all men. Raaga almost never recruits women. This, according to Kumar, is dictated not as much by small-town mentality as it is by the content of the plays and the nature of the craft. Raaga’s productions often rely on ‘Launda Naach’—a folk art common in Bihar and eastern Uttar Pradesh that can be performed only by men dressed as women. Such productions don’t need women, says Kumar. His plays dramatise topics like cross-dressing and transgender rights. Sharanya Ramprakash is trained in Yakshagana

Sharanya Ramprakash is trained in Yakshagana

SHARANYA RAMPRAKASH

Troupe: Dramanon, Bengaluru

Language: English, Kannada

Thespian Sharanya Ramprakash, 33, has directed seven plays since she co-founded Dramanon (Dramatist Anonyms) in 2007. The theatre group is active in Bengaluru and Manipal in Karnataka as well as in Hyderabad. Through her plays, she talks about identity crisis, the drudgery of modern life, hope for a better future and also the sensationalism of news by the media. She has directed The Original Last Wish Baby (an adaptation of William Sebring’s play on the media) and playwright Michael Frayn’s Alarms and Excursions (a series of short plays on technology in daily life). Ramprakash has trained in Yakshagana, and is working on a project that will combine this traditional form of dance-drama with modern theatre. Yakshagana relies on extravagant make-up and masks, and is traditionally performed only by men from dusk to dawn. She uses it to explore fluidity in gender identity and to raise awareness on gender discrimination and LGBT rights. A still from Comrade Kumbhakarna, directed by Mohit Takalkar

A still from Comrade Kumbhakarna, directed by Mohit Takalkar

MOHIT TAKALKAR

Troupe: Aasakta, Pune

Language: Marathi

His 2012 film The Bright Day may have received international acclaim, but theatre is 37-year-old Mohit Takalkar’s first love. He is a well-known face in Indian theatre, and with good reason, too. Since he launched Aasakta in 2003, he has staged 25 plays, almost all in Marathi. His body of work includes F-1/105 (about a couple’s plan to paint the walls of their apartment green and the politics of colour and identity), Uney Purey Shahar Ek (an adaptation of playwright Girish Karnad’s Kannada play, Benda Kaalu On Toast) and Gajab Kahani (a Marathi play based on José Saramago’s novel The Elephant’s Journey). Takalkar is currently directing Mukaam Dehru, Jila Nagaur, a Marwari and Hindi adaptation of the Marathi natak, Mukkam Post Bombilwadi. It is about a chance meeting of an uninvited guest who happens to be Adolf Hitler and a bewildering cast of characters who are trying to put up a ridiculous play in a forgotten Rajasthan village.

Pritesh Sodha in Vijay Tendulkar’s Baby PRITESH SODHA

Troupe: Utopia Communications, Mumbai

Language: Gujarati, Marathi and English

When he’s not using his business management degree to train employees in the fine art of communication, Pritesh Sodha, 32, likes to push the boundaries of experimental theatre. His body of work includes the Marathi play Tee (in the neglected horror genre) Gujarati production Ka Kanji No Ka (on the privatisation of education) an adaptation of the late iconic playwright Vijay Tendulkar’s Baby in Marathi (a story of a girl who works as an extra in the film industry and is exploited by a slumlord who treats her as a slave) and Pramey, a Gujarati adaptation of American playwright David Auburn’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play, Proof (on the life of an eccentric mathematician).

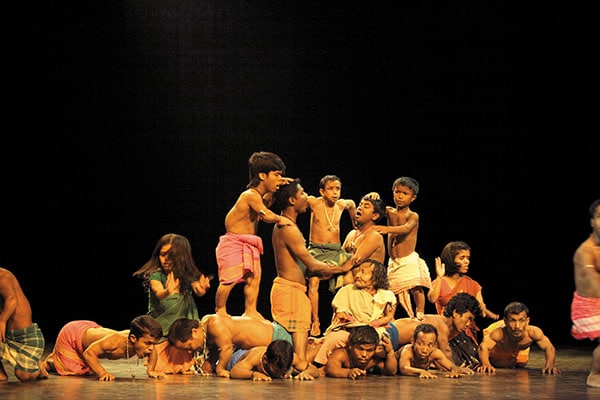

Actors from Pabitra Rabha’s Dapon group portray the struggles of a dwarf’s life in Kinu Kow (What to say)PABITRA RABHA

Troupe: Dapon (The Mirror), Assam

Language: Assamese

Dapon, which means mirror in Assamese, is a theatre group that embodies the big dreams of little people. It is a theatre company of dwarves. Pabitra Rabha, 40, an alumnus of the National School of Drama in New Delhi, eschewed the bright lights of the nation’s capital to set up Dapon in 2003, with the aim of giving a voice to men and women who are marginalised by society because of their appearance. His theatre company—based in Tangla, a remote part of Assam near the Indo-Bhutan border—has more than 35 dwarves from across Assam, most of whom are professional actors.

One of Dapon’s more popular plays is Kinu Kow (What to say) that highlights the struggles of a dwarf’s life. Rabha wants to build a culture village in Tangla or, as he sees it, a village of talented dwarves. Sonar Meye (Golden Girl) by Jana Sanskriti depicts the state of Indian women before, during and after marriage

Sonar Meye (Golden Girl) by Jana Sanskriti depicts the state of Indian women before, during and after marriage

SANJOY GANGULY

Troupe: Jana Sanskriti, Kolkata

Language: Bengali

Jana Sanskriti, Centre for Theatre of the Oppressed, is an old and well-respected theatre movement in Kolkata, but we have chosen to include it because it attracts young talent every year. It was founded by Sanjoy Ganguly, 58, in 1985, when he was influenced by Augusto Boal, a Brazilian theatre director, writer, politician and a founder of the Theatre of the Oppressed movement. Under the Jana Sanskriti banner, theatre troupes perform in villages across West Bengal and, along with locals, highlight their problems and concerns. Ganguly practices a form of theatre where a spectator can become an actor. He believes that in real life and in drama, a solution has to come from the people. Debates are part of his plays and, at times, a scene is performed multiple times until the audience finds a solution. The aim is to blur the lines between actors and the audience. Jana Sanskriti has 30 satellite teams of which 10 are all-women troupes.

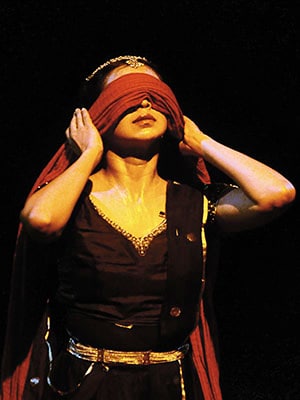

Sanjukta Wagh in Rage and Beyond: Irawati’s Gandhari

SANJUKTA WAGH

Troupe: Beej, Mumbai

Language: English, Hindi, Marathi

Kathak dancer Sanjukta Wagh, 35, approaches the art of storytelling and theatre through melody, dance and rhythm. Through Beej, the interdisciplinary initiative that she co-founded a few years ago, she uses the classical Kathak form to weave tales. Though she is firmly rooted in tradition, she is not afraid to push the boundaries of interdisciplinary art. Her work, she says, falls in the grey area between theatre and dance. Her solo act in Rage and Beyond: Irawati’s Gandhari—the play is a retelling of the Mahabharata from the point of view of the blindfolded queen Gandhari—won her the 2015 Mahindra Excellence in Theatre Awards for best actor in a lead role (female). Puja Sarup hosts a mask workshop in Bengaluru

Puja Sarup hosts a mask workshop in Bengaluru

PUJA SARUP

Troupe: The Patchworks Ensemble, Mumbai

Language: English

In his collection of essays, Per Amica Silentia Lunae (1918), poet William Butler Yeats wrote: “I think all happiness depends on the energy to assume the mask of some other life, on a rebirth as something not one’s self.” And it is through masks that Puja Sarup, 32, best expresses herself. She’s known for her role as Gertrude in actor and director Rajat Kapoor’s play, Hamlet, the clown prince. More recently, she and thespian Sheena Khalid founded The Patchworks Ensemble, which staged its first production, Ila, in December 2014. The play—based on author Devdutt Pattanaik’s book, The Pregnant King—expands on the themes of gender and sexuality. Sarup has an MA in theatre arts from the University of Mumbai, and has worked with European companies like Footsbarn Theatre and Buchinger’s Boots Marionettes. Actors in Aditi Desai’s Akoopar, which is about life in the Gir forest

Actors in Aditi Desai’s Akoopar, which is about life in the Gir forest

ADITI DESAI

Troupe: Jashwant Thaker Memorial Foundation (JTMF), Ahmedabad

Language: Gujarati

In the last decade, Aditi Desai, 57, has been pushing the boundaries of Gujarati experimental theatre. She founded JTMF in 2005, in memory of her father, the late Jashwant Thaker, a prominent Gujarati actor, director and activist. Desai’s plays are about the empowerment of women and the girl child. Her adaptation of the play Kasturba is a tribute to a woman who lived in the shadow of Mahatma Gandhi. Desai holds workshops for women, including those whose lives were shattered by the 2002 riots in Gujarat, to help them express their fears and worries. She has also worked with female prisoners. An actor in Samjhauta, a play directed by Pravin Kumar Gunjan

An actor in Samjhauta, a play directed by Pravin Kumar Gunjan

PRAVIN KUMAR GUNJAN

Troupe: The Fact Rangmandal, Begusarai (Bihar)

Language: Hindi

Caste politics, oppression, political pressure and propaganda: Protest theatre is 37-year-old Pravin Kumar Gunjan’s forte. He stages powerful plays in Begusarai, a small town in Bihar. Gunjan’s productions include Andha Yug (an anti-war drama set on the last day of the Mahabharata) and adaptations of Medea (a Greek tragedy by Euripides) and William Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Gunjan won the Mahindra Excellence in Theatre Awards for best director in 2012 for his play Samjhauta (which depicts a struggling young man’s world as a circus).

First Published: Oct 31, 2015, 06:36

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Aug 13, 2010 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)