Dust swirls above the hot ground as the SUV bumps its way through Raigad’s marketplace. Here in the interiors of Maharashtra, some 150 km from Mumbai, watermelons are piled up in pyramids on either side, as are heaps of okra and green chillies. Concrete shanties and the occasional general store soon give way to a dry, rugged landscape dotted with trees.

At Poladpur, one of the many blocks that make up Raigad, the vehicle halts. Tall, yellowing grass leads to Pradeep Kadam’s shed, a short walk away. Dressed in a collared blue tee, faded from overuse, and printed yellow shorts, Kadam doesn’t look like a businessman. Let alone a successful one. Yet that’s exactly what he is.

Three years ago, he took the plunge, packed his belongings and journeyed home. He had heard of the work Swades was doing in the region and reached out. Run by Zarina and Ronnie Screwvala, the not-for-profit promoted rural entrepreneurship by offering training modules in businesses like goat farming, poultry breeding and mango tree grafting. Kadam chose the former. “I already had 5-6 goats,” he says. Swades’s staff trained him in the finer aspects of rearing the animals after which they gave him one female goat and her two babies, one male and one female.

Since then, Kadam has expanded his breed to 50 goats which he then sells to interested farmers, mostly from neighbouring villages. He built the shed, a large, elevated shelter for his herd where Forbes India visited him, with the monies he has earned being in business. That’s not all. Given his newfound expertise, Swades recently appointed him as a vendor to buy and sell goats on behalf of others for which he gets a commission. “From my own goats and the Swades vendorship, I earned around Rs 1.5 lakh last year,” says Kadam. As he speaks, a black-furred goat bleats without relent, drowning out his voice. He picks her up, strokes her and keeps talking. “I am 100 percent confident of tripling my income in the next 1-2 years,” he says.

Swades was born out of the Screwvala’s dream to lift one million rural Indians out of poverty every 5-6 years. But rather than dole out freebies, the couple sought to empower individuals with the tools and training they needed to become self-sufficient. They chose Raigad as their first stop—“it had to be a place that was close enough to Mumbai for us to visit often”, explains Zarina—where Swades’s work covers 2,500 villages spread across seven blocks, impacting a little over half a million people.

After selling UTV, their media conglomerate, to Disney in 2012, Zarina and Ronnie were clear they wanted to focus more on philanthropy. While running UTV, the duo had set up a creche and an old-age home within their then-office premises in Saki Naka, a suburb in Mumbai. But they were hungry for greater impact, and importantly, they wanted to combine their business chops with their giving. “We didn’t want to be a cheque-writing foundation. We wanted to be an execution foundation,” says Zarina, sitting out of their cheerful, open planned office in Worli, also home to Upgrad, Screwvala’s edtech venture.

They were inspired by BRAC, a Bangladeshi charity founded by Sir Fazle Abed that focuses on a holistic model of community development. “The scale and vision at which Sir Fazle was working blew our mind. The idea for a 360-degree model of development and the belief that it was possible came from there,” gushes Zarina. “At the time no one was doing 360 and everyone laughed at us when we told them we’re going to do this. They said do one thing and do it well. But as entrepreneurs we’re used to failing, so that didn’t bother us,” she smiles. Adds Ronnie, “Besides, the goal had to be audacious enough for us to focus our time and attention on it.” So while Swades started out in 2013 by focusing on education, it soon started plugging the gaps it saw in water and sanitation, health and nutrition and economic development in Raigad.

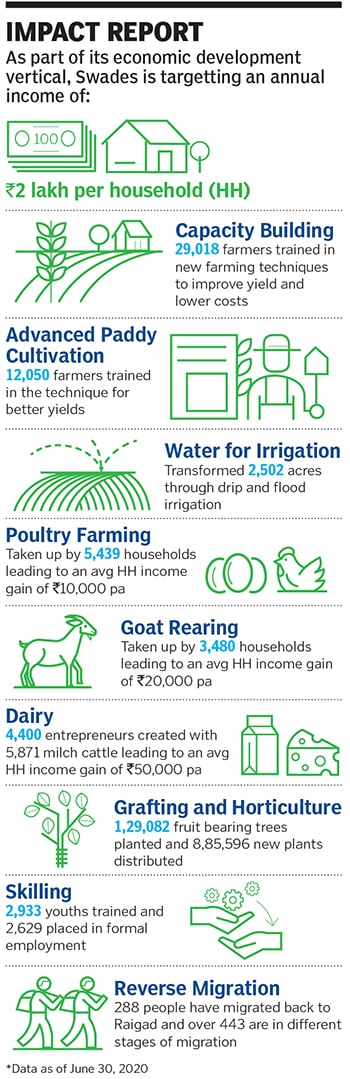

“One of our aims is to increase the annual income of every household to at least Rs 2 lakh,” says Ronnie. Bottom-up entrepreneurship, of the kind taken up by Kadam, is key to that.

![swades foundation_raigad_212 swades foundation_raigad_212]() Vikas Kadam has moved on from his life at a chawl in Pune, where he used to work as a car mechanic, to poultry farming and a two-bedroom house in Raigad

Vikas Kadam has moved on from his life at a chawl in Pune, where he used to work as a car mechanic, to poultry farming and a two-bedroom house in Raigad

In fact, not only are Raigad’s residents encouraged to take up one of Swades’s livelihood initiatives offered under its economic development vertical, but so are those who are, at present, working in cities like Mumbai and Pune. Reverse migration of this sort has become increasingly popular over time. Already 280 migrants have returned home switching from dreary, low-paying jobs in cities to running flourishing businesses in Raigad.

The coronavirus pandemic has hastened the return for several more, says Prasad Patil, general manager at Swades. But unlike in other parts of the country where they’ve returned to bleak prospects, in Raigad, the possibilities are plenty, thanks to Swades. Take the case of Sankesh More. The 33-year-old used to work in a jewellery store in Mumbai’s Girgaum area, helping with odd jobs and pocketing Rs 15,000 a month, he says, over a crackling phone line from Raigad.

He lost his job when the lockdown was announced and decided to return to home, lugging his family and their spare belongings onto a tempo. The Mores scrounged on their savings for the first few weeks as jobs were hard to come by in the village. As it became increasingly clear that the lockdown would stretch on, More, worried and desperate, reached out to Swades—so ubiquitous in the area that he knew exactly whom to contact. To his advantage, he owned a one-acre plot, albeit a barren one, attached to his house. Swades’s team advised him to resoil the land and cultivate paddy—a widely grown crop in the region—and gave him lessons in the technicalities. “Overnight I went from being a small-time employee in a big city to an owner-farmer at home,” says More. While it sounds implausible, Sandeep Devmore, Swades’s assistant manager at Raigad’s Mhasla block who oversaw More’s training says, “Proper training was given to him first over the phone and then one-on-one. We even tested his knowledge before giving him the resources he needed to start off.” In fact, they taught him advanced farming practices to improve the quality and yield of the crop. In the course of the next few months, More expects to earn roughly Rs 20,000 for his produce and, in the meantime, is also exploring other entrepreneurial opportunities with Swades.

![swades swades]()

The SUV hiccups along Raigad’s roads and screeches to a halt near poultry farmer Vikas Kadam’s house (unrelated to Pradeep Kadam). Hens scuttle in alarm and stray dogs bark at the vehicle. An autorickshaw is parked just outside the cement porch of Vikas’s two-bedroom, brick-lined house. “I used to live in a tiny chawl with five others in Pune,” says Vikas, who sports a goatee, a tight T-shirt that shows off his bulging biceps and dark glasses pulled up on his head. He worked as a mechanic for Honda for a couple of years, but soon got disillusioned with the rough city life. “I couldn’t even save any money because I would earn a mere Rs 7,000, most of which would go towards paying my rent and other expenses,” he says.

Swades runs monthly meetings in Mumbai and Pune for migrants looking to return to Raigad. These are held in large halls and are attended by 40-50 people, says Sameer D’Souza, director, economic development and market linkages, Swades. They are told about the opportunities back home often those who have successfully made the shift are present to give a first-hand account of their experience, while others who are in the process of reverse migrating attend to sort out their documentation, change of address and other formalities. “Once they decide to return home, we help them every step of the way,” adds D’Souza.

Vikas attended one such meeting and was convinced about returning home. He did so in mid-2018 and promptly took up training in chicken breeding offered by Swades. At the end of the drill, he was given a batch of 21 newborn chickens, for which he had to pay Swades a nominal amount. “The first two weeks of a chicken’s life are very important. The mortality rate is the highest at this stage. Hence poultry farming is a skill,” says Patil. Vikas did as he had been trained and after two months when the birds were old enough, he sold them to interested parties and made a `10,000 profit. He repeated the cycle a couple of times and profited from it each time. Soon Swades appointed him as an “anchor farmer”, which means it provides him with batches of one-day-old birds to nurture and takes them back after a month. Those birds are then given to other farmers.

Vikas earns an additional Rs 8,000 a month for this work. His earnings have enabled him to buy an autorickshaw—the one that is parked outside his house—which he ferries around every afternoon for some side income. “My wife has also learnt how to take care of the chickens during the critical period, so often she looks into that business, while I drive the rickshaw. That helps us get two incomes,” says Vikas.

But that’s not all. Vikas, 35, has already started making provisions for the future. He heard about an orchard plantation programme being run by Swades, where one is taught how to plant and grow alphonso mango saplings using a technique called grafting. Herein, saplings are inserted on to existing plants that are non-fruit-bearing but have already taken root, so as to hasten the growth of the mango tree. “The saplings only yield fruit after five years, but thereafter one benefits from a handsome yearly income,” says Andhere. “Internally, we joke that it is like a pension for your old age.” Vikas has put his small plot behind his house to use by grafting 10 alphonso plants.

Through an intricate network of village development committees or VDCs that comprise village elders as well as the youth, men as well as women and ‘sakhis’ who regularly visit villagers’ houses in their designated areas, Swades is able to carry out its work on the ground. VDCs are similar to village panchayats, while sakhis are like friends who know intimate details about Swades’s beneficiaries. “If you truly believe in an exit strategy like we do, you have to believe in empowering people. Empowerment comes from the community owning the programmes,” says Zarina. For example, a sakhi who was assigned to goat farmer Kadam’s house, would often chat with his wife, Sujata. During one such conversation, she told her about the need for good quality cattle feed that could be made using wild, locally grown herbs. “I told her it would benefit their own goats,” says the sakhi. Sujata decided to experiment with it, saw it worked wonders and decided to make large batches to sell to other farmers. Today she heads a women’s self-help group that makes and sells this feed. Just in the first two months of operation, they sold roughly 650 units of cattle feed and earned `1.5 lakh, she says.

Self-sufficiency is the foremost aim, especially because as per Zarina and Ronnie’s plan, they are to pull out of a region every 5-6 years and move to another area. By that time, they hope VDCs are empowered enough to elect their own leaders and handle matters. So do they plan on exiting Raigad anytime soon as it’s been six years? “It’s something we’ve been thinking about,” says Zarina. “I doubt we’ll pull out in entirety but slowly we will have to.” Swades soon plans to enter Nashik.

If there were any doubts about the villagers’ level of self-sufficiency, the pandemic has laid those to rest. The infection has meant that Swades’s team from Mumbai hasn’t been able to visit Raigad, forcing VDCs to fill the void. Training sessions for the entrepreneurial initiatives, for example, are usually conducted by Swades’s staff. Now they simply train the VDCs via Zoom. The VDCs in turn use a combination of videos made by Swades, telecons and WhatsApp messages to train their village folk. Says Patil, “We now know that they can do it.”

Trained by Swades Foundation, Raigad goat farmer Pradeep Kadam (with his wife in the picture) earned around Rs 1.5 lakh last year

Trained by Swades Foundation, Raigad goat farmer Pradeep Kadam (with his wife in the picture) earned around Rs 1.5 lakh last year Vikas Kadam has moved on from his life at a chawl in Pune, where he used to work as a car mechanic, to poultry farming and a two-bedroom house in Raigad

Vikas Kadam has moved on from his life at a chawl in Pune, where he used to work as a car mechanic, to poultry farming and a two-bedroom house in Raigad