Sliding tariffs mean more power, but is the trend sustainable?

A number of strong factors are boosting the growth of solar and wind power in India, but doubts persist over viability

In 2013, Rahul Munjal, chairman and MD of Hero Future Energies, part of the Hero Group, was talking to the India team of one of the largest consulting firms in the world to give them a mandate. The energy vertical of this firm, which Munjal doesn’t name, had all its leaders focussed on conventional energy. This April, Munjal was talking to the same firm again, when he learnt that their energy vertical now has more partners looking at renewable energy (RE) than thermal power.

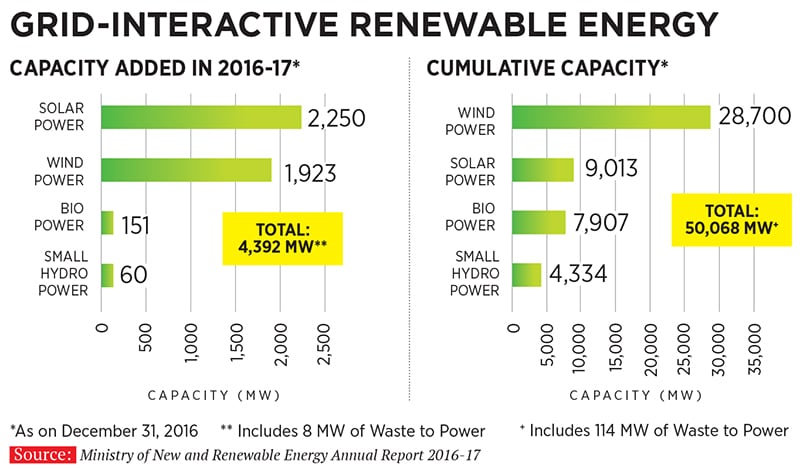

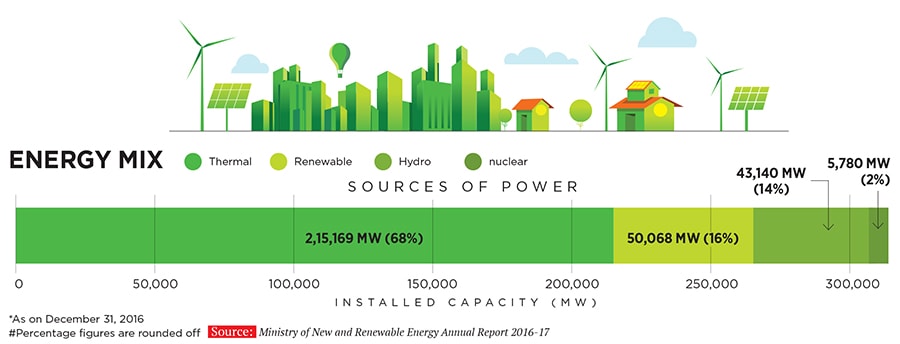

“This is the kind of paradigm shift that has taken place in India’s energy sector,” says Munjal. “Renewables are now the preferred source of power in India, not just due to issues of morality and ethics, but because it is economically viable.” FY2016-17 has seen the addition of a record amount—more than 11 GW (1 GW equals 1,000 MW)—of RE capacity, mostly in the solar (5,526 MW) and wind power (5,400 MW) sectors it has, for the first time, caught up with thermal power capacity added during the same period.

This is a long way from a decade ago when RE technology was expensive and tariffs high—Rs17 per kWh (kilowatt hour), compared to Rs3-4 for thermal power. “There was criticism that RE wasn’t a business to be done and there was doubt about whether India will even reach the earlier RE target of 20 GW that it had set for itself,” says Inderpreet Wadhwa, CEO of Azure Power, an India-focussed clean energy firm.

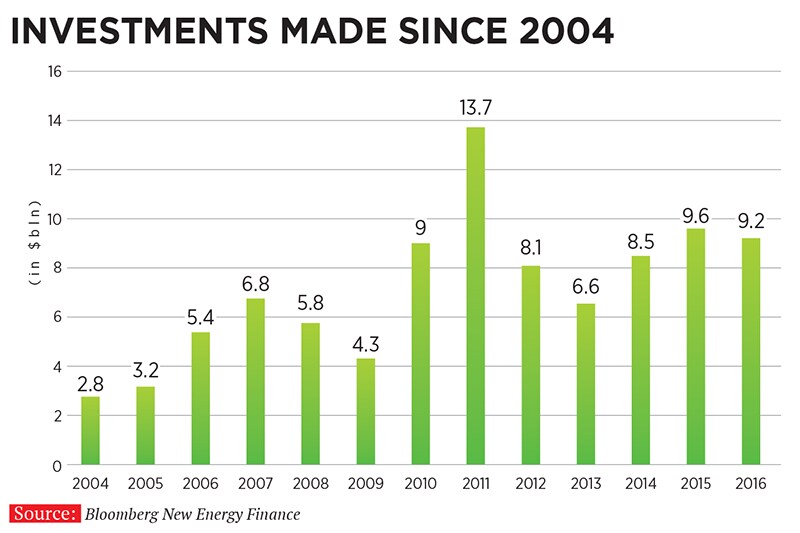

But, over the last few years, a concerted governmental push to promote clean energy, access to advanced and cheap technology (such as solar photovoltaic cells from China), and the availability of global equity funding have made RE a sunrise sector. In 2009-10, the government’s target of installing 20 GW by 2022 had appeared impossible. Compared to that, the present government, in 2015, revised the target to 175 GW by 2022. Consequently, the sector has received investments of $14 billion (debt and equity) in 2016-17, double of what it had received in the previous fiscal.  Sunny Side

Sunny Side

Since 2010, the cost of Chinese photovoltaic cells (PVCs) have fallen by around 80 percent. China, the world’s largest market for solar panels, has a production capacity of 90 GW, says Sumant Sinha, chairman and CEO of ReNew Power Ventures. But the actual global offtake is only 60 to 65 GW, due to a slowdown in RE capacity addition in China and Japan. The excess capacity is expected to keep PVC prices down. This will benefit India.

Anil Sardana, managing director and CEO of Tata Power says falling cost of PVCs and other expenses of setting up a plant, and the cost of capital, which has become cheaper, “make a good case for tariffs to be low”. That the rupee has been appreciating against the dollar also makes it cheaper to import equipment. Sinha says the total capital cost of developing 1 MW of solar energy has fallen by as much as 20 percent in the past five years to around Rs4 crore.

Wind energy prices, too, have fallen since 2010. In February, projects totalling 1 GW were tendered at a tariff of Rs3.40 per kWh. What’s interesting is that this decline is for capacity to be commissioned after FY18, when the projects will not enjoy government sops like generation-based incentives, and accelerated depreciation at the rate of 80 percent in the first year (revised guidelines allow for 40 percent). Sinha says the unit economics of wind energy have improved with new technology enabling greater plant load factor (PLF) even at sites with low wind intensity.

It isn’t only global investors who are eyeing India’s clean energy sector domestic companies are also taking note. Highlighting this is Tata Power’s acquisition of Welspun Energy’s clean energy capacity of 1,140 MW, last June, for Rs10,000 crore. Sardana says Tata Power’s portfolio of solar assets was “insignificant” and it would take long years for it to reach the acquired numbers organically. “The role of thermal power is to meet base-load requirements, whereas RE meets the variability above base load,” he says. “Considering that demand increase has been subdued compared to supply-side growth, thermal capacity utilisation has been adversely impacted. It is unlikely that any new thermal capacity would be added in the next few years beyond what’s in the making already.”

Flip Side

But the question is: While declining tariffs are good, at what point do they become unviable? “We aren’t confident that the current low levels [of tariff] are sustainable, given the cost of debt, even though such cost has come down in recent times,” says Ankur Ambika Sahu, co-head of Goldman Sachs’ merchant banking division in Asia Pacific. Goldman Sachs is a majority stakeholder in ReNew, and Sahu its nominee director on ReNew’s board. Such low tariffs may not continue to attract capital either. “There is bound to be a process of rationalisation when bids don’t see new capital coming in,” he adds.

But there are indications that IRR is slipping further. A report by credit rating agency ICRA says a project with a levelised tariff of Rs3.15 per kWh can earn an IRR of less than 10 percent, based on an assumed capital cost of Rs4.5 crore per MW and a PLF of 21 percent. “The viability of such tariff for project developers from a credit perspective will be critically dependent on the availability of long tenure debt [18 to 20 years post project completion] at a cost-competitive rate, the ability to keep the cost of PV modules within budgeted levels, and execute projects in a time-bound manner,” writes Sabyasachi Majumdar, senior vice president and group head, ICRA, in the report.

One of the reasons for falling tariffs is the lack of adequate projects coming up for bidding, due to a subdued demand for RE power and an abundance of coal. State discoms are also waiting for RE tariffs to stabilise, since no one wants to overpay. Discoms are also not penalised for not meeting their renewable purchase obligations. (States and union territories, collectively, fall short of their cumulative 2016-17 target by 39 percent, or close to 6,900 MW.)

Discoms also do not pay producers on time. A report by Mercom Capital Group, a clean energy market intelligence firm, estimates that discoms in Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Telangana have delayed payments by three to four months.

“There are a lot of underlying issues that the government needs to address, like discom financials, transmission and evacuation issues, on-time payments and payment guarantees,” says Raj Prabhu, CEO of Mercom Capital.

“Limited capacity drives fierce competition, and India is one of the best RE markets that global capital is chasing,” says Wadhwa. “So, there is some irrational exuberance.”  The Future

The Future

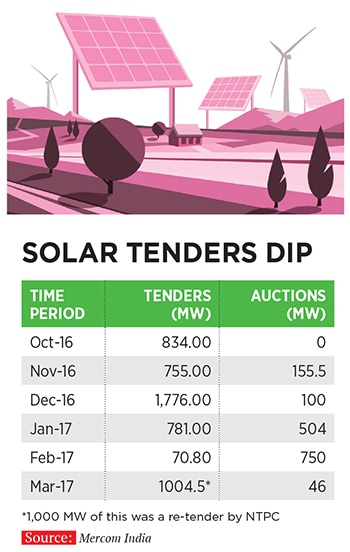

Although India added more than 11 GW of RE in 2016-17, it was behind the government target of 17 GW while additions in wind energy exceeded the target, solar power fell short because of delays in awarding and execution of projects.

As on March 31, the installed capacity for solar and wind energy is close to 60 GW this means another 100 GW needs to be added over the next six years, at an average of 17 GW a year. ICRA estimates solar energy addition to increase to around 7.5 GW in FY2018, sustained by the momentum of projects already in the pipeline 40 percent of the 100 GW-target is expected to be met by rooftop solar projects. According to a report by Bridge to India, an RE consulting firm, the cumulative installation of rooftop solar in India is about 1,247 MW, as on December 31, 2016. The report estimates that 11.9 GW of rooftop capacity will be added by 2021.

The industry expects FY18 to be a lull year for wind power, with growth picking up in 2018-19. The uncertainty caused by the shift from feed-in tariffs to reverse auctions has delayed projects being tendered. Tanti, however, believes that 5 GW can be added this fiscal if more projects are announced and awarded soon.

The current pace of capacity addition will be insufficient to meet the 2022 target. At the moment, the industry is expecting the government to make a dash closer to the finishing line, and is pinning its hopes on a proactive power minister, Piyush Goyal, to channelise the tailwinds.

First Published: May 26, 2017, 06:05

Subscribe Now