Importance of making yourself indispensable

The best-selling author and 'Ultimate Entrepreneur for the Information Age' describes the importance of making yourself indispensable.

You recently said that “There are no longer any great jobs where someone tells you precisely what to do.” What are the implications for today’s workers?

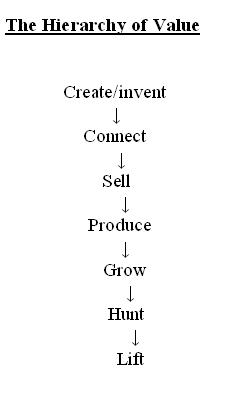

The fact is that today, any type of work that can be done ‘by the book’ can easily be moved to someone who will do it for cheaper. And companies have to do this, because the competition is doing the same thing -- there is this ‘race to the bottom’ going on. What this means to the modern worker is one of two things: either you need to accept the fact that you are part of the race to the bottom -- which isn’t good, because you just might win or you need to do work that cannot be written down in a manual. If the work you do is work that only you can do, that creates scarcity, which is the goal in the modern workplace. What needs to be done at the business school level – and at the elementary and high school levels -- is to spend way more time helping people develop unique skills and not worry so much about making them be compliant and able to do a bunch of things on a checklist.

Basically, you believe that we must become indispensible in order to thrive going forward. How does a person become what you call a ‘linchpin’?

The short definition of a linchpin is, ‘someone who would be missed if they were gone’. The nature of the industrial system was to have an organizational chart, and if someone didn’t show up for work, you didn’t shut down the factory -- you just put someone else in their spot. A linchpin is someone who doesn’t have a spot like that these are people that we depend on, and if they go missing, it’s a big problem. Job seekers have to decide, are they looking for an opportunity where they get to make an imprint and be counted on? Or, are they looking for a job that could be filled by many different people, where they could be replaced in a day? Basically, you can either fit in or stand out – not both today’s workers are either defending the status quo or challenging it.

What is ‘emotional labour’, and why is it now so much more valuable than physical labour?

The term comes from Arlie Hochschild, a UC Berkeley sociologist who studied Delta Airlines stewardesses. She described emotional labour as the kind of work where you have to present specific emotions as part of the job – for instance, you have to smile even when you don’t feel like it. Today, that’s pretty much all we’ve got left. Certainly, anyone reading this interview is not swinging a sledgehammer all day for money what we do now is, we get paid to bring emotional labour to the table: we are paid to bring enthusiasm or commitment or persuasion or confidence to a situation where, maybe in that moment, we don’t feel like it. The good news is that emotional labour is both scarce and well compensated. If, on the other hand, you think the solution is ‘more rules and less humanity’, you will be disappointed by the results: the organizations that can bring humanity and flexibility to their interactions with other human beings are the ones that will thrive.

In what ways are modern workers ‘artists’ and their jobs ‘platforms’?

‘Art’ is about a lot more than painting. Art is the act of a human being doing something that has never been done before. It’s what happens when a human being connects with somebody else and makes an impact. Sure, sometimes that involves a painting or a sculpture or a theatrical play, but it can also be the way a doctor deals with a three-year- old who’s not feeling well. In Louis Hyde’s brilliant book The Gift, he says that a key aspect of art is that it always has a ‘gift’ component to it. Looking at a Pablo Picasso painting or listening to a Paul McCartney song doesn’t cost anything it’s free -- a gift from the artist to the person who receives it. Likewise, the notion that we can use digital networks to connect people, to contribute an idea or do something that benefits a tribe or society -- those are all gifts. Once you get in the habit of giving these gifts and bringing emotional labour to the table, you are much more likely to create art and once you start making art, you may discover that you’ve become a linchpin --that you’re scarce and highly valued.

You have said that in today’s environment, ‘depth of knowledge’ on its own can get people into big trouble, and that schools should teach only two things: how to solve interesting problems and how to lead. Please explain.

I just wrote a book about that called, Stop Stealing Dreams [available free online at stopstealingdreams.com ] where I argue that innovative organizations such as Wikipedia and the Kahn Academy have eliminated the need for us to memorize stuff, because we now all have access to any information in just three keystrokes. As a result, you will never again hire someone merely because they have access to data, because we all have access to data. You are going to hire people because they can solve a problem that hasn’t been solved before, because the problems that have been solved before are easy to look up. That’s why the skills of connecting people, standing up for what you believe in and making a difference are now significantly more important than your ability to solve a quadratic equation. It’s not that depth of knowledge is of no value: when it is combined with good judgment, diagnostic skills or nuanced insight, it is still worth a lot.  You have criticized traditional hiring practices, particularly the focus on resumés. What should replace the resumé, in your view?

You have criticized traditional hiring practices, particularly the focus on resumés. What should replace the resumé, in your view?

If you really think about it, a resumé is merely a chronicle of a lifetime of compliance. It says, “Here are examples of companies you have probably heard of where I was hired to do exactly as I was told.” This is still a good way to get a job where you are going to be told what to do but the alternative is to have a body of work -- a trail that you’ve left behind of things you have accomplished and problems you have solved. There are lots of ways to describe that now you can do it online or you can do it on a piece of paper. My point is, the important part isn’t the piece of paper it’s being able to point to a trail, being able to say, ‘I’m the guy who wrote this part of Linux’, or, ‘I’m the woman who got this person elected.’ Once you have a ‘list’ of the impact you have made on the world, getting a job will be easy, because these are the kind of people employers seek out. By the time an ad is listed in the newspaper or on Craigslist, the employer has already announced that they are just looking for a cog for their machine.

It doesn’t always pay to be a Linchpin: an ‘average’ senior programmer gets paid about the same as a ‘great’ one who delivers significant value. If money isn’t motivating linchpins, what is?

The notion that people are motivated by money alone has been disproven again and again. Of course, some people are motivated by the ‘story’ of money Warren Buffett isn’t focused on making more and more money because he’s spending more -- it’s because that’s how he keeps score. Generally, what we do as human beings is, we keep score of something, and it’s usually respect and the way we feel about the work we do and how we feel about our co-workers. If you look at surveys that have been done over the last 10 years about how people feel at work, the bosses always think people are motivated by money, and the employees consistently say that they would much rather work hard for credit, authority, responsibility and respect. There is a huge mismatch in what employers think motivates people and what actually motivates them.

What are some of the organizations that are thriving by enabling linchpins?

It’s difficult to provide a list because inevitably, as companies grow, they find themselves under pressure to standardize and scale their systems. So a company might have 20 or 30 people in it who are irreplaceable, but then it goes public, and the next thing you know, it figures out how to replicate the system again and again.

What I will say is that almost all of the jobs in North America are being created by small, un-famous organizations. I got an e-mail a couple of months ago from someone saying, “Please help me. I need introductions so I can get a great linchpin job at Google or Apple.” And my answer was, “The time to get a linchpin job at Google or Apple was 10 years ago. You need to go find an unknown company where you have the freedom to move around enough to make an impact early on.” The better a company is doing and the more famous it is, the more difficult it is to earn the trust you need to stand out.

You have said that access to capital and appropriate connections are not as essential as they once were, and that the biggest shift in today’s economy is self determination. Are people up for this challenge?

Not everyone, that’s for sure. A lot of what I’m talking about is easily countered by people who will say, ‘That is all fine and good, but who is going to pick up my garbage? And who is going to assemble my iPad?’ To that I say, of course someone needs to do these things, but it doesn’t have to be you. What we’re dealing with right now is the following: anyone who wants to start a business today can build a cash-flow positive business for one fiftieth of what it cost 10 years ago, because the cost of reaching a worldwide market has dropped to zero, and the cost of finding people to produce what you make has gone down to a trivial number. The connection economy has transformed all that, so that once you have a business that makes a little bit of money, raising more money for it is easy. What is hard is making money in a business that has no future.

As for connections, I personally haven’t set foot in the Century Club, the Harvard Club or any of the other clubs in New York City in a decade. Why would I? The fact is, if you speak up online and your ideas have currency, people are going to show up and want to connect with you. What we need more of are people with the guts and the emotional labour to do this – not people who were lucky enough to get into a particular elementary school so they could get into Harvard later on and get the ‘right job’. The greatest shortage in today’s society is an instinct to produce.

Training Tomorrow’s Linchpins

The sign in front of your local public school could say:

We train the factory workers of tomorrow. Our graduates are very good at following instructions, and we teach the power of consumption as an aid for social approval.

Imagine a school with a sign that read:

We teach people to take initiative and become remarkable artists, to question the status quo, to interact with transparency. And our graduates understand that consumption is not the answer to social problems.

Seth Godin is the best-selling author of 15 books that have been translated into 38 languages. His latest is We Are All Weird (The Domino Project, 2011). He holds an MBA from Stanford, and was called "the Ultimate Entrepreneur for the Information Age" by BusinessWeek.

First Published: Jan 09, 2013, 06:23

Subscribe Now