Making music, then and now

No more sucking up to labels, technology has turned musicians into self-sufficient pros

Used to be, the music universe was ruled by great wielders of power known as record companies. Also called labels, and permeated by men referred to by the intended pejorative “suits”, these companies had immense control over a vast and disparate tribe of social deviants known as musicians. The labels had dominance over nearly every aspect of those tribe members’ most personal creations—their songs. (There was even a time when the suits tried to name themselves as songwriters, even if they didn’t know the difference between a chord and a cord.)

The musicians remained beholden to the labels because the only investment they could afford was their time, skill, talent and conviction. The labels had coffers thick with coin, and so were able to fund the expensive processes of recording and release. That was merely the beginning of the indentureship. Every successive process in the chain of development remained in the iron grip of the labels: The publishing of the works, their distribution and their marketing. The ever self-empowering companies tightened their grasp by cartelising the business even further by engaging in conference room deals with other similarly expansionistic entities such as record stores, radio stations and TV channels. The only throughway to any of those outlets was via that conduit of conspirators, so if you wanted to spend your life making music professionally, your only option was to get a recording contract. And thus be in debt forever, because those houndstoothed, shark-finned, bespoked gents recouped every last paisa they spent on you. And then gave you a sliver of silver-plating for your efforts.

Then came the internet. And Napster, and BitTorrent, and 50 mbps broadband connections. And down went the papier-maché palaces. Record companies downed their shutters like shopkeepers during a bandh. The house began to be rebuilt—by craftsmen bearing tools of their own. Technology brought back the power to the people. Now not only do they create, they also control those creations. They offer their message to whoever is interested directly, untainted by the grubby, greedy hands of corporate behemoths.

Today, wherever you are in the world, you can connect with others who think like you, or dig what you do. There are no filters or funnels but the ones you employ to share the music you toiled for lifetimes to make. Social networking and online distribution sites form the level playing field you always wanted.

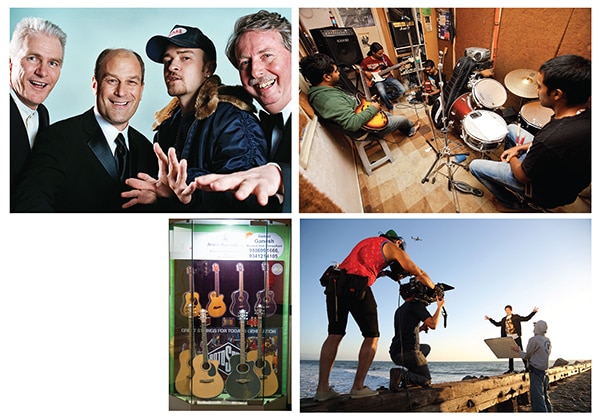

Clockwise from top: Justin Timberlake with BMG music executives members of the band Galeej Gurus in their one-room studio in Bangalore a music video being filmed AX660R guitars for sale in Bangalore

Clockwise from top: Justin Timberlake with BMG music executives members of the band Galeej Gurus in their one-room studio in Bangalore a music video being filmed AX660R guitars for sale in Bangalore

Used to be, that to make a music video, you had to have a lot of money. If you didn’t have a lot of money, you had to find someone who did and who wanted to spend it on you. For musicians, that meant trying to convince record companies that you were worth the bullion needed to fund a sexy vid. If they said yes, you were their slave for life. The other option was to find a business partner, which is how my band Indus Creed managed to do it in the virginal days of music television in India. We were able to convince a sponsor to cough up a chunk of cash for our videos, in exchange for which we would shill their product at our live concerts via banners and backdrops. The reason you had to jump through these hoops was because making a video was a bloody expensive proposition—and that was even after your filmmaker buddy had agreed to do it for free. It felt a bit weird, spending more money on hamming it up to a single song than you had to record the entire album.

Today, all you’ve got to do is find a young gun with their own Canon 5D (it looks like a regular DSLR camera and isn’t anywhere as expensive as the pro-video cams of yore), a few lights, a laptop with the very affordable editing suite known as Final Cut Pro and a batch of neat concepts. It probably won’t look like Peter Gabriel’s Sledgehammer or Michael Jackson’s Smooth Criminal… but who in the world is making videos like that anymore anyway?

Used to be, you needed to sweet-talk a returning overseas relative to bring you a half-decent instrument because the local knockoffs weren’t even good enough to beat the dust off your mattress. And that’s after you sweet-talked your folks into forking over dad’s Diwali bonus towards a device they were convinced would lead you into the abyss of drugs and damnation. Today, all you’ve got to do is ride a rickshaw a few kilometres from home to behold a candy-store collection of all the gear you need to record the magnum opus you’ve been writing ever since you discovered Porcupine Tree.

Used to be, you had to convince your parents that being a musician didn’t necessarily mean living a dead-end life as deadbeat. And could they please increase your allowance as you’ve got greater needs now—like guitar strings.

Today, you can cite a slew of self-sufficient pros whose lives exist entirely within a continually expanding micro-universe of music-making, and it’s not all just jingles and Bollywood. Achhe din aa gaye!

The author is the lead singer of Indus Creed

First Published: Dec 13, 2014, 07:22

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Mar 19, 2010 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)