Walmart: The click and the dead

What Walmart's entry means not just for ecommerce but also for physical retailers

Image: Dhiraj Singh / Bloomberg via Getty Images

Image: Dhiraj Singh / Bloomberg via Getty Images

Aneesh Reddy wasn’t expecting the kind of response he got for a small Artificial Intelligence (AI)-based software and hardware solution he launched about six months ago, starting with some of VF Corporation’s India stores.

Most would know VF better through its many brands such as Wrangler and Lee jeans. Reddy, co-founder of Capillary Technologies, recalled in a recent interview, how his AI-enabling product, VisitorMetrix, became one of his fastest growing ones, recently hitting $1 million in annualised revenue run rate.

“Our fastest selling product in the last six months is VisitorMetrix, our AI-based footfall counter for offline retail stores,” Reddy said. “We released that product six months ago as a simple use case—counting how many people visited a store—because it was our first AI-based software and hardware product.”

But “it just sold like crazy, because suddenly all these offline players were saying, ‘I want to track conversions in-store’. Just as the online commerce businesses were tracking conversions on websites, suddenly you have the physical retailers speaking the same language,” says Reddy.

“We wanted to enhance the performance of our stores through technology,” Pankaj Agarwal, retail director of VF Brands, said in a press release in October 2017, when Capillary and VF announced their collaboration on VisitorMetrix. “We will be using Capillary VisitorMetrix’s real-time analytics capability at 70 percent of our brand stores across India.” This would help VF measure the store’s ‘key performance indicators’ accurately, giving it a “strategic edge” in improving store performance, he said. Data analytics would improve both the front-end, with the sales staff, and back-end operations, helping managers better understand same-store performance over extended periods of time.

Agarwal added: “This will help enhance value for the consumer at the store. The goal is to optimise our resources ensuring they align with the demands of our consumers.”

This kind of ‘how do we use data better in offline stores’ trend is definitely catching up, says Reddy. Everyone has picked up on the fact that if one has to fight the online players, one needs to learn from them—the way they use data.

Fight for supremacy

This change has been in the making for some years, but an epochal milestone was reached in May when Walmart, the world’s biggest retailer, decided to reach Indian consumers via ecommerce first, by spending $16 billion to pick up a 77 percent stake in the country’s biggest online commerce company, Flipkart. Walmart has its ‘Best Price’ business-to-business stores in India, but it isn’t allowed to open its own direct-to-consumers multi-brand retail brick-and-mortar stores in the country as per existing rules. The buyout is only the latest event in the ongoing online retail war in India that is sapping the energy of the offline players.

Image: Vikas Khot

In the last four years, Amazon has shown that it has the know-how to win in India. While Flipkart had a six-year head start over the Seattle-headquartered etailer, it is a leader in India only by a modest margin. And there are categories such as groceries where it lags its American rival, and some like entertainment where it doesn’t even have a presence. Amazon for its part is following through on its well-orchestrated ‘Prime’ ecosystem strategy.

The fight for supremacy between Amazon and Flipkart has already claimed one large local victim, Snapdeal, which scaled down dramatically as valuations crashed and losses piled up. But it also hurt local physical retailers a lot because of the discounts offered online that the brick-and-mortar businesses struggled to match. The entry of Walmart will hasten that trend, Reddy says.

“Walmart isn’t here for the value that Flipkart is offering now, but for the next 15-20 years, for which it will have to focus on the logistics, infrastructure, last-mile delivery, warehousing and so on,” Satish Meena, a senior forecast analyst at consultancy Forrester, said in an interview. “This is going to be good for the ecosystem and the focus will shift to areas other than discounting and sustainable growth will get more importance.”

“Look, Flipkart wouldn’t have survived on its own, that’s for sure,” says Atul Jalan, founder of one of India’s most successful cloud software companies. Jalan’s Manthan Software Solutions sells CRM and data analytics software to retail chains in America and Europe. He is now piloting Maya, a speech-recognition-based

AI assistant for chief executives of any retail chain.

“The writing was on the wall, and it [Flipkart] wouldn’t have been able to sustain the losses. It needed somebody with deep pockets and also someone with the ‘savoir faire’ of running this business at scale,” Jalan said. “It had to be gobbled up, either by Amazon or Walmart. I’m happy that it’s Walmart because this will continue to keep India’s ecommerce scene potent and full of vitality.”

The competition for India between the two American giants will now bring a lot of economic activity that will create value, and Jalan expects that Walmart will at some point bring its whole ‘farm-to-fork’ supply chain practices to India. “And it is going vitalise that part of the backend in India,” he said.

This will result in an environment different from the one in which billions of dollars were burnt in 2014 and 2015 when Flipkart and Snapdeal competed for customers and didn’t pay attention to customer experience, in comparison to Amazon, says Forrester’s Meena. On the other hand, Amazon, in four years, managed to take a third of the market on the sheer strength of its know-how in logistics, infrastructure and customer experience. Discounting won’t work in the long term in winning customer loyalty, says Meena.

Category wars

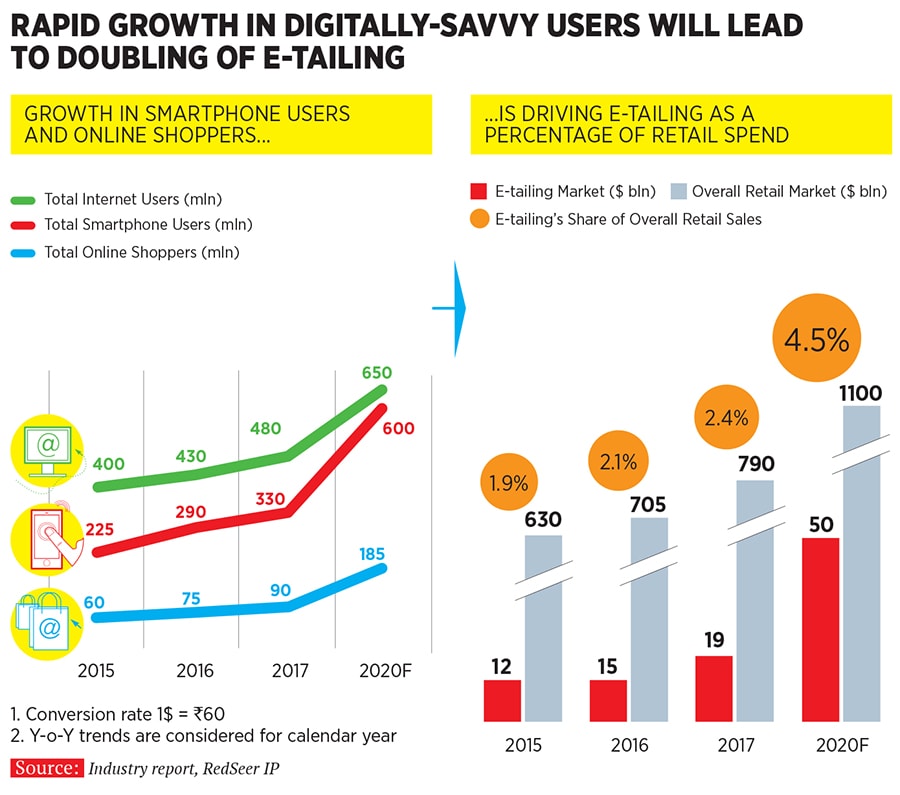

“Organised retail is already under pressure the world over,” says Meena. Even in India, if one goes category by category, initially online retail hurt books and music—with businesses such as Crossword and Planet M taking the hit. Then came smartphones, with 33 to 37 percent being sold online, Forrester estimates. That proportion will be much higher if one were to look only at urban areas.

The next big category that companies are targeting is fashion. This is a category in which organised retailers are big and their penetration, in big cities and towns, is high. It’s a challenging time for stores like Shoppers Stop because a large chunk of fashion purchases is happening online and Amazon is just getting started.

In September 2017, Shoppers Stop, promoted by real estate group K Raheja Corp, sold a 5 percent stake to Amazon for close to Rs 180 crore, and struck parallel agreements to list its entire portfolio of over 400 brands on an exclusive microsite on Amazon’s marketplace in India. Shoppers Stop will also open Amazon experience centres within its own network of stores across the country, the company said in a press release. The partnership would “deepen” Shoppers Stop’s online presence, says Govind Shrikhande, managing director.

“Brick-and-mortar companies are investing at double the speed in technology, people, experience and assortment. Omni-channel has huge potential and digital journeys of customers need to be tapped rigorously. Although online shopping is less than 1 percent at the overall level, digital influence in many categories has crossed 20 percent. This is an important metric,” says Shrikhande.

The same month, Aditya Birla Group shuttered its online store ABOF.in because it could no longer sustain the bruising discount war with the pure ecommerce players.

Ultimately, as Jalan anticipates, groceries will become the next big battleground, although market penetration currently is negligible (online and offline). There are four significant online players: Grofers, BigBasket, Amazon and now Walmart.

Over the longer term, physical retailers—except for bellwethers like the Future group and DMart—may have little option but to become more specialty-oriented—apparel, jewellery, restaurants. Second, expect local retail houses to do a lot more targeted ecommerce. Walmart’s business to business line, called Best Price, has an outlet in Mumbai, which really isn’t a store, but what it calls a ‘dark store’—just a warehouse, where the retailer either places an order via an app on a smartphone or a small salesforce goes out and takes orders. This allows Walmart to do away with the need of having a full-fledged front-end store.

Category by category, as physical retailers come under pressure they will also ask the government to relax funding norms for them, Meena expects. After the Walmart-Flipkart deal, the government should have a relook at the existing policies, he says. The transaction warrants that India should open its FDI (foreign direct investment) rules further “so that monies can come into offline retail also,” says TP Pratap, co-founder at Qwikcilver Solutions.

“India’s retail ecosystem is likely to be dominated by Chinese and American platforms. Reliance Industries and Future Group would definitely be a part of this battle,” quips Shrikhande. “Currently, the level-playing field of FDI funding is missing for the brick-and-mortar sector. As and when retail FDI changes and new collaborations between players happen, the picture will be more clear.”

First Published: May 22, 2018, 15:51

Subscribe Now