Omnigrid's Unique Solar Power Model

OMC's model of supplying solar lamps to homes and solar power to telecom towers in rural UP looks like a bright idea. But can it keep it shining?

For as long as he can remember, Mohammad Fahim’s life was ruled by the sun. The 25-year-old artisan from Meer Nagar village in Uttar Pradesh’s Hardoi district, and his family—parents and five siblings—would tirelessly embroider exquisite designs with zari on fabric, for which neighbouring Lucknow is renowned. Their work-day would begin at sunrise and end at sunset a phenomenon common to most of the 90 households in Meer Nagar.

Hardoi, contiguous to the state capital, is officially ‘electrified’. This means, poles and wires reach the villages, but perhaps not electricity.

“We had a connection once. But it had a minimum cost of Rs 250 a month, rarely gave us more than five to six hours of electricity, and that too at odd hours like in the middle of the night. What good is that?” asks Fahim.

But, three months ago, his life was changed by a lantern that his uncle got from OMC (Omnigrid Micropower Company). “It was a simple lantern, but it gave the best white light for almost six continuous hours. And we did not have to pay anything upfront. Just Rs 4 per day,” says Fahim.

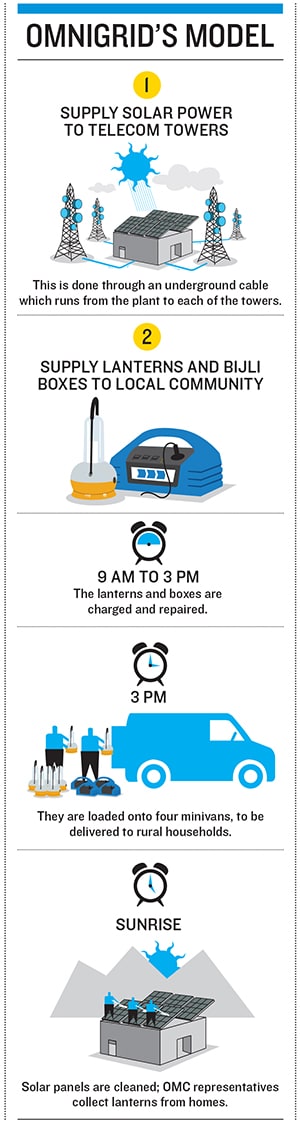

OMC provides solar powered lanterns to rural homes without access to a reliable supply of electricity from the grid. The charged lanterns are delivered to homes in the evening, and collected early in the morning to be recharged. OMC also supplies charged battery units, called bijli boxes, for basic household requirements.

Fahim subscribed to OMC’s monthly scheme for four lanterns. Earlier, his family had used a kerosene lamp, which was not good enough for work, study or cooking. But now they can work between 6 pm and 11 pm as well, thus doubling their income.

Almost half the households in Meer Nagar have a lantern subscription.

OMC’s primary focus, however, is not to supply solar lanterns to villagers, but to provide cheaper solar power to telecom towers in rural areas. Lack of electricity in rural India means most of these towers are run on diesel.

Since June 2012, OMC has launched 10 micro power plants in Hardoi, each plant catering to at least two telecom towers and about 3,000 homes in the vicinity. OMC estimates its lanterns are reaching 1.5 lakh people. It aims to power 5,000 plants in the next three to five years, mostly in UP, Uttarakhand, Bihar, Jharkhand and the North Eastern states.

An Odd Model

OMC’s model stands out among others in India in its ability to straddle two very different sets of clients: Villagers and telecom tower companies. In doing so, it seems to have hit upon a rarity—a financially viable business model for selling solar power without depending on government grants or subsidies.

In the middle of 2011, OMC Chairman Sushil Jiwarka, CEO Anil Raj and COO Rohit Chandra first thought of shifting from the telecom sector—where they had all had long stints—to energy. But there was growing realisation that the next stage of fast growth in the energy sector would not come from conventional sources.

“So, we sat down to analyse what the problems afflicting the telecom growth in the country were… because every problem represents an opportunity,” says Chandra. They found that half of the 4 lakh telecom towers in the country were in rural areas, and almost all of them ran on diesel.

Depending on geography, diesel costs were two to five times the cost of grid electricity. Making matters worse for telecom companies is the fact that the average revenue per rural user is almost a fifth of the urban user.

OMC’s research showed they could provide cheaper solar power to telecom tower companies. But this was not the only opportunity.

There is huge demand for power among rural communities. But neither are they willing to pay a fixed monthly rental for irregular supply from the grid, nor are they willing to pay an upfront price—more than Rs 10,000—to set up solar panels on their roofs. “Our experience in selling telecom products had taught us how the rural customer is acutely price sensitive and avoids heavy upfront expenditure,” says Chandra. Moreover, villagers did not want to get saddled with the maintenance of solar panels.

“We applied the pre-paid approach instead of the post-paid one,” says Raj. “Just like we needed wireless technology, instead of landlines, for telecom to reach rural areas, similarly we had to go beyond wires to provide power to rural India.” This meant providing lanterns for as low as Rs 4 per night. For heavy users, OMC has a bijli box, which can run a couple of fluorescent tubes and a fan, and charge mobile phones. Those who can’t afford a monthly subscription order a single lantern or a bijli box for as low as Rs 5 per evening.

The problem faced by companies that have tried to target the rural community alone is the difficulty in maintaining a steady revenue stream, especially from the first day itself. For others who are selling just solar power to telecom towers, it is not enough to justify the heavy capital investment.“But, tackled together, odd as it may look, the two disparate clients made it a viable model,” says Chandra.

Typically, it takes Rs 50 lakh to put up a plant with a capacity of 9 kW to 18 kW. The plant, spread over 5,000 sq ft to 10,000 sq ft of rented land, can be scaled up to 50 kW.

Chandra says, since it is an infrastructure project where an asset’s life is 20 to 25 years, it would take six to seven years for a full payback on capital and operating expenditures. “Our initial experience has been very encouraging we find that a plant breaks even at the direct op-ex cost within six months.”

Till now, most of the investment in OMC has been private, but “at the right time” in future Raj and Chandra plan to go public.

The Doubt

Telecom tower companies couldn’t be happier. Not only has the cost of running the towers dropped, the rural telecom business has also picked up.

“In the past, we have experimented with other models but they did not work this well,” says Sairam Prasad, CTO, Bharti Infratel, the only company that has a formal agreement with OMC. Negotiations are on with another power major.

For rural folks, the OMC lanterns have changed their lives. Children can study and women can cook after sunset, without the costly and polluting kerosene lamp.

But, while OMC is catching the attention of other entrepreneurs in the solar energy sector, there are doubts about the scalability of its model. Nikhil Jaisinghani, co-founder of Mera Gao Power, says, “One of their biggest challenges would be to find financing for the next phases of expansion. Not to mention the high costs of transporting the lanterns,” he says.

“It is a transportational nightmare, but it depends on the entrepreneurs,” says Harish Hande of Selco. “I am not sure if we should equate distribution of power to distribution of mobile phones. Power is a more long term concern than mobiles… OMC has at least shown the way.” There are also doubts about how far a company can go if it sells lanterns and bijli boxes alone.

The soft spoken Anil Raj responds, point by point.

Reducing distribution costs is at the heart of OMC’s strategy. They are experimenting with solar powered bikes in Hardoi, which they hope will replace their small trucks. Also, instead of delivering lanterns, OMC will switch to replacing the batteries.

“We plan to expand through the franchise model. But beyond the geographical expansion, we are interested in scaling up our products,” says Raj. These include:

First Published: May 23, 2013, 06:34

Subscribe Now