Making REITs work

Real estate investors Thomas Bohjalian and Jason Yablon find bargains in luxury shopping centres and other unappreciated properties across America

Jason Yablon and Thomas Bohjalian in their Manhattan headquarters. If you must own an office Reit, make sure it owns buildings housing programmers, like Kilroy Realty

Image: Jamel Toppin for Forbes[br]At the glamorously landscaped mall on Sand Hill Road in Silicon Valley, shoppers stroll through the Hermès and Peloton outlets, jockey for a seat in the showroom Teslas and wait in a long line stretching out from the bakery. But is this hangout for the rich doomed? The very venture capitalists and Python programmers who pour dollars into it on weekends spend their working hours on schemes to extend ecommerce and make malls obsolete.

Ask the two guys who pick common stocks for the Cohen & Steers Quality Income Realty Fund, Thomas Bohjalian and Jason Yablon. They trade real estate investment trusts, which are pools of properties like stores and office buildings.

They have a knack. Over the past decade this $1.5 billion (net assets) closed-end fund has delivered a return averaging 21 percent a year, six percentage points ahead of the S&P 500. That return was helped, but only somewhat, by leverage it’s after deducting a hefty 1.3 percent in expenses.

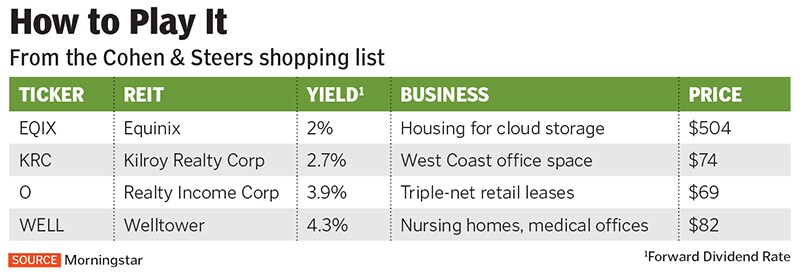

Three years ago, when Reits with retail assets looked cheap in relation to their earnings, Bohjalian and Yablon started selling them off. Counterintuitively, they added expensive Reits, like Equinix, which owns data centres, and Invitation Homes, which rents houses.

[br]Bohjalian predicts that two thirds of malls will fold by 2029. But in a declining industry, there’s room at the top. Simon Property Group, which owns that ritzy outdoor mall in Palo Alto, is a likely survivor it is in the Quality Income portfolio.

The fund has increased its stake in Realty Income Corp. It mostly owns free-standing retail buildings leased to tenants like convenience and drug stores that are resistant to online competition.

Look beneath. Urban Edge’s real estate is near dense population areas, where demand for condos and medical offices will not go away. Lacking retail tenants, a landlord can always get a wrecking ball. “Picture a [shopping] centre 60 miles outside of Manhattan,” Bohjalian says. “Everything it sells you can get on the internet. What’s the value of the dirt it’s sitting on?” He says the management of Urban Edge is skilled at repurposing messed-up shopping space. He puts the Reit’s worth at a third more than the $17 share price.

To get an edge, target one slice of the market. Bohjalian, 53, has been a Reit tracker for 28 years. Yablon, 40, had the misfortune to start out as a telecom equipment analyst in 2000. That job quickly evaporated, but he saved his career by switching from optical fibre to bricks. Their employer, the publicly traded Cohen & Steers, is also focussed. It says it was the first money manager to specialise in listed real estate securities.

As its prime earnings figure, a Reit reports “funds from operations” or FFO. FFO is net income with depreciation added back in and non-recurring items, like capital gains from asset sales, taken out. The Reit also reports how much of this profit was siphoned off for capital expenditures. Capex is tricky, says Yablon. “Does it create value or is it defensive?”

The $12 million spent on a new lobby might add to a building’s future lease rates or it may be no more than a desperate play to keep existing tenants from moving out. Yablon says that office landlords eat up 20-30 percent of net operating income on capex that does no more than keep them running in place.

Bohjalian and Yablon track obscure statistics—like megawatts and influenza rates. Trends in power consumption at data centres figured into their decision to own a collection of them called Dupont Fabros, despite that firm’s stumbles in finding tenants. They started buying at $38 not long before a takeover deal worth $61 a share came along.

Flu? Some Reits lease space to nursing home operators. The operators live off thin Medicaid margins. When a bad flu season causes residents to depart for either hospitals or cemeteries, the Reit suffers. Last year the market overreacted to trouble at Welltower. Bohjalian and Yablon started buying at $54 shares that now go for $82.

One theme at Quality Income will last a long while: The power of things digital. Their biggest warehouse position is in Prologis, which is adept at online commerce they prefer landlords on the West Coast they’re overweight data centres they like cell towers (American Tower Corp and Crown Castle International Corp). But they are wedded to no position and in love with no management. “A great company can be a bad stock,” says Bohjalian.

First Published: Sep 16, 2019, 13:50

Subscribe Now