How social media has altered our relationship with food

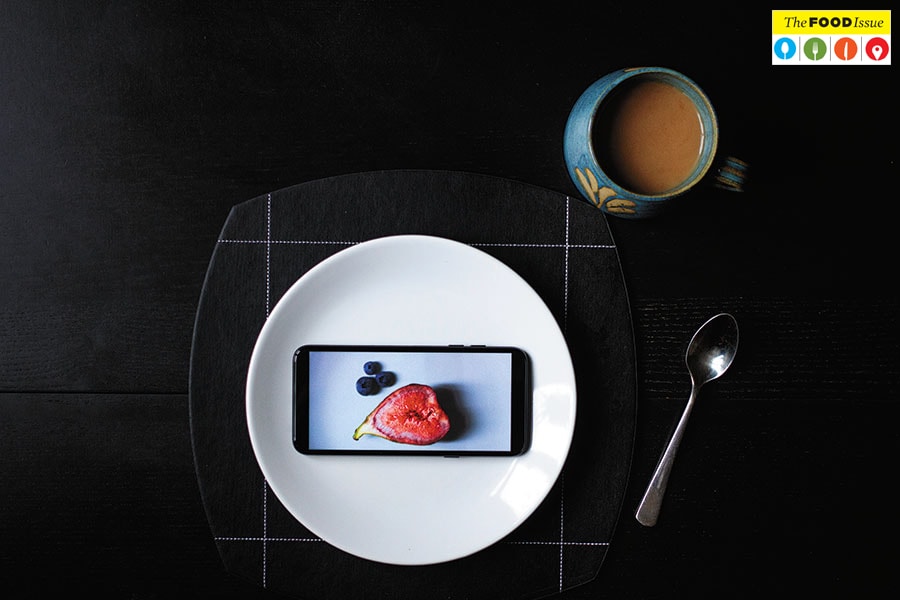

Eat, shoot and love: A generation of Instagrammers is changing the way we eat—and cook

Image: Joel Sharpe/Getty Images[br]Of the many wonderful moments in the 2007 Pixar animated film Ratatouille, the most heart-warming is perhaps the one in which Anton Ego, the ruthless and feared Parisian food critic, is served a plate of the ordinary dish after which the film is named. As he tastes a spoonful of the ratatouille, he is prepared, pen in hand, to be his usual scathing self. Instead, he is transported to a memory of himself as a sniffling boy standing at his kitchen door, having fallen off his bicycle, and being served a plateful of steaming hot ratatouille by his loving mother. The food critic blinks, his pen escapes his grip, and he is a transformed man, gulping down the dish that has touched his soul.

Image: Joel Sharpe/Getty Images[br]Of the many wonderful moments in the 2007 Pixar animated film Ratatouille, the most heart-warming is perhaps the one in which Anton Ego, the ruthless and feared Parisian food critic, is served a plate of the ordinary dish after which the film is named. As he tastes a spoonful of the ratatouille, he is prepared, pen in hand, to be his usual scathing self. Instead, he is transported to a memory of himself as a sniffling boy standing at his kitchen door, having fallen off his bicycle, and being served a plateful of steaming hot ratatouille by his loving mother. The food critic blinks, his pen escapes his grip, and he is a transformed man, gulping down the dish that has touched his soul.

Food, and memories of it, touch all of us in a way that few other things do. They transport us to the past, where we associate flavours and aromas with the people we shared them with, to moments of celebrations and joy, of warmth and comfort conversely, they take us to moments in the future that we aspire for, associating them with experiences that we would like to have. It is little surprise then that food is what people want to talk about, share pictures of, and build connections through on the modern day platforms of social media its universal appeal has the power to transcend borders and cultures, and bring joy, even if for a fraction of a moment, till the next swipe.

“Social media is like the bulletin board of our lives,” says Sambit Mohanty, national creative head of JWT (J Walter Thompson, a marketing communications brand). “And food is the invisible thread tying us all together. We want to tell people about the awesome dinner we had, and how beautiful the setting was. We want the world to appreciate our good luck, and good taste.” The intrinsic voyeuristic nature of social media, he adds, is what has helped make food a dominant subject. “Food is always connected with memories and stories. And we want to broadcast these stories to the world through social media.”

That food also makes for attractive photographs (even when taken by amateurs on cellphones in semi darkness). That is another reason why it is one of the most popular subjects on social media. “Instagram is a visual medium,” says Pooja Dhingra, a pastry chef and founder of Le15 Patisserie. “When you enter a pastry shop, you first eat with your eyes. The same emotion applies to food photographs.” Mohanty adds that appealing images of food “evoke primal feelings with us, of hunger, lust and desire. It’s a Pavlovian reaction. But only a great looking product is not enough it has to tell attractive stories”. Till the second week of August, Instagram had 351 million posts related to food, thanks to the practice of diners clicking multiple pictures of their food even before touching it.

It’s not just amateur food enthusiasts who are contributing to this abundance: The food and beverage industry has taken to social media like duck to water, thanks to its many advantages—the ability to do away with intermediaries like advertising agencies and news media for marketing and promotions (thus cutting costs), building a direct connection with their consumers, showcasing their star performers and their creations, and receiving feedback.

“What social media has done is provide tremendous access to food,” says Manu Chandra, chef partner, Toast & Tonic, Monkey Bar, The Fatty Bao, and executive chef of Olive Beach. “Earlier it was only through mainstream media such as newspapers and magazines, and later through television—with shows such as Sanjeev Kapoor’s [Khana Khazana]—that we could know about food. Today we come to know about food from different content creators.”

Accessibility has improved so much, that today you can watch [British celebrity chef] Gordon Ramsay cooking his best dishes, and make what he is making, says Yash Bhanage, co-founder of Hunger Inc Hospitality, which runs The Bombay Canteen and O’ Pedro.

What chefs and restaurateurs also agree on is social media’s ability to connect them directly to their consumers. “Like many other sectors, if you are in the food business, it is imperative to be on social media, irrespective of the level at which your restaurant is,” says Chandra. “We are able to put out our own narrative, and it has helped us in a big way. Friends have become influencers, and vice-versa.”

Chandra, however, adds that it really does not mean much to have followers and ‘likes’ on social media if people are not walking into your restaurants to eat what you are cooking. “That is the real test of what you are doing,” he says. “I would never really be a television chef where I cook, then eat my own food and say how wonderful it is. How will people know how good it is, unless they eat it themselves?”

The fact that The Bombay Canteen and O’ Pedro manage their own social media handles, instead of getting an external agency to do it, means they have figured out a balance in the content they put out. So, every post is not about the food and drinks they make some are about the ingredients they use—“we say, this what we are doing with it in our restaurant, and this what you can do with it at home,” says Bhanage—or even the chefs who are working behind the scenes. Today’s guests, he adds, often do a Google search for images and menus of restaurants so that they get an idea about it before going there.

For Prateek Sadhu, executive chef and co-owner of Masque, social media has been a way to connect not just with consumers, but also producers. “It has helped me connect with a lot of farmers and growers, from who we source our raw material,” he says. “We also engage with our consumers, who are curious about what we do, and the fact that we are serving Indian food in a new manner.” Sadhu adds that for standalone restaurants like Masque, social media platforms have been helpful in promoting themselves, since costs are far reduced than conventional marketing methods.

“Social media altered my inspirations,” says Ranveer Brar, chef and TV show host. “When you work in the kitchen, your world is small. Through social media you realise the bigger things that are at play. I now want to delve into the history and culture of food.” He admits that even without social media he would feel the urge to discover more about cuisines and cultures, but digital platforms make it easier to “find solace in camaraderie”.

But social media is a double-edged sword, for the brickbats can come as thick and fast as the bouquets. “At a personal level, I used to be active on Twitter. I used to follow people I admired. But then I had a meltdown and stopped being on the platform,” says Chandra. “This is because anyone can make any claim on social media, without any veracity.” Subsequently, Chandra has separated his professional and personal lives on social media.

Bhanage says that while his restaurant staff are trained to pay attention to feedback on social media—“if there are 10 comments saying Eggs Kejriwal is too salty, then perhaps it is”—it can also prove to be a knife’s edge, where customers resort to blackmail. Guest expectations can also be influenced by what they have seen on different platforms. “They should not walk in expecting a dish to look a certain way, and then find reality to be different,” he says.

“Sometimes people look at social media as a formula for success,” says Brar. “If their presence on these platforms stems from the love of food, it is fine. But if they are taking a formulaic approach, and not having genuine experiences themselves, it’s not fine.”

***** Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh SurpurOne of the good things about social media is its democratic nature, and the fact that it is an equaliser. Nowhere else in the real world would you have millionaire, celebrity chefs competing with home cooks, with no formal training, for the attention of viewers and subscribers or celebrated food critics competing with vloggers showcasing street food in obscure cities. So, if British chef and restaurateur Jamie Oliver has 4.4 million subscribers on his YouTube channel, Noida-based home cook Nisha Madhulika has 7.4 million. Oliver, with his crew of producers, camerapersons and editors, creates content that is shot in studios, his home or his restaurants, while Madhulika started with a single-camera setup at home.

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh SurpurOne of the good things about social media is its democratic nature, and the fact that it is an equaliser. Nowhere else in the real world would you have millionaire, celebrity chefs competing with home cooks, with no formal training, for the attention of viewers and subscribers or celebrated food critics competing with vloggers showcasing street food in obscure cities. So, if British chef and restaurateur Jamie Oliver has 4.4 million subscribers on his YouTube channel, Noida-based home cook Nisha Madhulika has 7.4 million. Oliver, with his crew of producers, camerapersons and editors, creates content that is shot in studios, his home or his restaurants, while Madhulika started with a single-camera setup at home.

Similarly, Pune-based Kabita Singh started a YouTube channel, Kabita’s Kitchen, in 2014 with a video of how to make bhindi fry. The channel now has 5.3 million subscribers. “YouTube has proved that even a homemaker like me can create videos that are watched by millions of people, and make a successful living out of it,” says Singh. “I didn’t think anything like this would happen, and was expecting only some friends and family members to watch the videos.”

Singh believes her videos are popular because they have a down-to-earth feel, and are particularly helpful for people living alone. Shot in her own kitchen, they include everyday recipes as well as drinks and food that people usually order in restaurants. “Earlier, recipes of basic cooking were popular, but now the expectations of viewers have increased,” says Singh. “They want to try something new, but with ingredients that are easily available and not expensive.”

“Social media has created a level-playing field,” says Bhanage. “Young and aspiring chefs get a voice of their own, and don’t need to depend on a restaurant or hotel to showcase their talent.” He adds that it has also been a boon for local eateries that can be known across the world. “India needs to highlight all these hidden talents.”

“Somebody like Anthony Bourdain, for instance, made street food such an adventure,” says Mohanty of JWT. “He made you want to try out food that you otherwise would not touch with a barge pole.”

But you don’t always need Bourdain to introduce you to unknown cuisines. Today, thousands of vloggers from around the world trawl the web of lanes and alleys of cities and villages, known and obscure, to unearth restaurants and street food vendors. So, you can follow Artger (a YouTube channel) into homes in Mongolia, and watch family members having milk tea, khailmag (caramelised clotted cream) and boortsog (butter cookies) for breakfast, or The Food Ranger through the lanes of Peshawar as he tries out charsi tikka kebab, or go along with Aden Films to watch a Japanese chef serve up a $140-dollar Kobe beef steak. The possibilities are limitless.

“I have not been to any country yet where people don’t take pride in their food,” says Mark Weins, a Bangkok-based food vlogger with 4.7 million subscribers. “They can be shy at first, but as soon as I start talking about food, they smile and begin to open up.” Weins started vlogging in 2011, after blogging about food for a few years. “I was always drawn to food from the time I was a child. I did not particularly like writing, but I would because it was an informative blog. And then I realised that I myself don’t like reading. Instead I like watching videos. That’s when I turned vlogger.”

*****

In the 1977 film Priyatama, by Basu Chatterjee, a newly wed Dolly (Neetu Singh) tries her hand at cooking for the first time with disastrous results. Her only recourse is calling home, in a different city, every morning at 10, to take notes and recipes from Suleiman, the resident bawarchi. Consequently, she runs up a telephone bill that her husband can barely afford. Today, all that Dolly would have to do is look up YouTube on her phone.

Learning about food, and learning how to make and eat that food, has perhaps never been easier. Thanks to the internet we don’t even need to step out of our homes or offices to buy groceries, let alone figure out the many steps of making unfamiliar and complicated dishes to impress our families and friends with. And yet, it has also never been easier to do away with cooking altogether. The mushrooming of restaurants, takeaways, and delivery services mean you can order whatever you want to eat, without breaking a sweat.

Regardless of the choices you make, what wins is the love of food.

First Published: Sep 02, 2019, 06:18

Subscribe Now