The hyperloop is fast as a plane and cheaper than a train

The race to turn Elon Musk's vision for high-speed travel in steel tubes is officially on. Buckle up

The majestic Senate majority leader suite in the US Capitol was still Harry Reid’s in September when he eagerly scooched his leather chair across the Oriental rug to gaze at something that, he was told, would change transportation forever.

Former SpaceX engineer Brogan BamBrogran (yes, that’s his legal name) pulled out his iPad for a preview. Two business partners, the near-billionaire venture capitalist Shervin Pishevar and former White House deputy chief of staff Jim Messina, carefully studied the powerful senator’s reaction. Even Mark Twain, a onetime riverboat pilot whose portrait hung over Reid’s desk, eyed the proceedings warily.

“What’s that?” asked Reid, sitting up, animatedly pointing at the iPad. BamBrogan’s home screen showed a photo of a desert plain with dazed and dusty people wandering around at sunrise.

“Er, that’s Burning Man,” the engineer responded, then clued in the 75-year-old politician to the techno-hippie carnival that takes place pre-Labor Day in the Black Rock Desert of Reid’s home state of Nevada.

BamBrogan’s formal presentation was even wilder, a vision for efficiently moving people or cargo all over the Southwest, to start, and the world, eventually, at rates approaching the speed of sound.

At the end of the 60-minute pitch Reid sat back and smiled. That’s when Pishevar leaned in, asking the senator to introduce him to a Nevada businessman who owned a 150-mile right of way from Vegas to California for a high-speed train. Reid said he would, and they shook on it. And thus fell another obstacle in the group’s fast-moving efforts to actualise what until recently had seemed not much more than geek fantasy: The hyperloop.

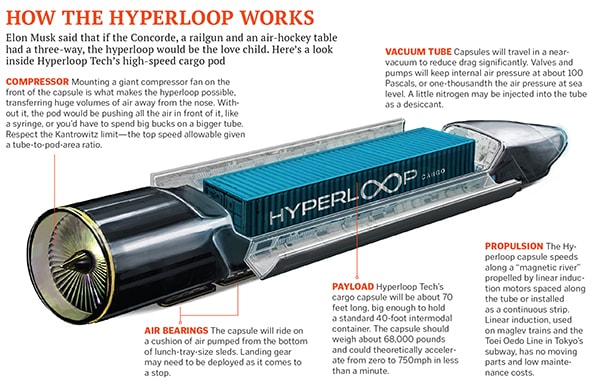

You remember the hyperloop, don’t you? It’s that farout idea billionaire industrialist Elon Musk proposed in a 58-page white paper in August 2013 for a vacuum-tube transport network that could hurtle passengers from San Francisco to Los Angeles at 760 miles an hour. Laughed off as science fiction, it is as of today an actual industry with three legitimate groups pushing it forward, including Hyperloop Technologies, the team in Harry Reid’s office. They emerge from ‘stealth’ mode with this article, armed with an $8.5 million war chest and plans for a $80 million round later this year. “We have the team, the tools and the technology,” says BamBrogan. “We can do this.” The 21st-century space race is on.

It’s hard to overstate how early this all is. There are dozens of engineering and logistical challenges that need solving, from earthquake-proofing to rights-of-way to alleviating the barf factor that comes with flying through a tube near the speed of sound.

Yet it’s equally hard to overstate how dramatically the hyperloop could change the world. The first four modes of modern transportation—boats, trains, motor vehicles and airplanes—brought progress and prosperity. They also brought pollution, congestion, delay and death. The hyperloop, which Musk dubs “the fifth mode”, would be as fast as a plane, cheaper than a train and continuously available in any weather while emitting no carbon from the tailpipe. If people could get from Los Angeles to Las Vegas in 20 minutes, or New York to Philly in 10, cities become metro stops and borders evaporate, along with housing price imbalances and overcrowding.

The only thing this geek fantasy is missing: Musk. With his hands full running Tesla Motors and SpaceX, he’s left it to others to make his theory a reality. He declined to comment for this story. But his fingerprints are on each of the groups vying to build the hyperloop, even though they couldn’t be more different.

Hyperloop Technologies is the Dream Team, enlisting a formidable lineup of Silicon Valley and Washington superstars, most with a strong connection to Musk. Pishevar, the 40-year-old poised to break into the billionaire ranks thanks to his investment in Uber, is a Musk intimate and the one who forced his friend to publicly reveal his hyperloop vision in the first place. His new Sherpa Ventures fund led Hyperloop Technologies’ seed round, along with Formation 8, overseen by Joe Lonsdale, another young (Forbes 30 Under 30) centimillionaire hyperloop enthusiast and co-founder of Big Data colossus Palantir. Now add Messina, who oversaw President Obama’s 2012 re-election campaign co-chairman David Sacks, who worked under Musk at PayPal before scoring big at Yammer Peter Diamandis, founder of the X Prize Foundation, on whose board Musk sits and BamBrogan, who until recently was one of Musk’s key SpaceX engineers. Musk has received regular updates from this group. President Obama has been briefed as well.

Even more surprising than the platinum-plated roster: Hyperloop Tech’s initial mission. They intend to go way beyond Musk’s original vision and focus first on freight rather than human transportation. This high-speed ‘cargo loop’ could go over land or under water. Imagine submerged skeins of steel tubes crisscrossing the ocean or up and down the coasts hurtling shipping containers at near supersonic speeds. Need iPhones? Press a button and a container-load is on its way from Shenzhen overnight.

Against this establishment lineup of all-stars, Dirk Ahlborn’s scrappy crew feels like the Bad News Bears. Also based in LA and boasting a similar name, his Hyperloop Transportation Technologies (HTT) has the numbers: 200 engineers, designers and others who, for the past year, have essentially crowdsourced the hyperloop. Launched with a call to arms on Ahlborn’s site JumpStartFund, HTT now has permanent moonlighters from Cisco, Boeing and Harvard who work strictly for equity. They’re organised into a federation of teams tackling different aspects of the hyperloop: Financial models, cabin and station design, capsule engineering. “At a certain point we’ll need a full-time team and to raise money,” says Ahlborn, “but right now it’s working well.” HTT plans to present its latest work at big railroad trade shows in Dubai and Johannesburg later this year.Meanwhile, a group of Musk’s own SpaceX engineers have been agitating to get in on the action. In January, Musk announced cryptic plans to fund the construction of a hyperloop test track in Texas, with no date specified. Just as Musk “open-sourced” his initial hyperloop concept in 2013, he says he plans to make the track available to any group that wants to test a design.

The vision for the Texas test track is something out of Star Wars—pod racers flying through the air, would-be rebel forces facing off against the Empire. Which isn’t a bad analogy for this whole nascent business. “We’re peering into a process that hasn’t happened before,” says Pishevar. “It has risk, but this is an idea that can change the world.”

Sci-fi writers and other dreamers have long envisioned fast, tubular travel. Rocketry pioneer Robert Goddard in 1909 wrote a paper that wasn’t too far off from Musk’s proposal. In 1972 Robert Salter of the RAND Corp conceived a supersonic transcontinental underground railway called the Vactrain. Shervin Pishevar was one of those dreamers. Back in the dot-com era, he floated an idea called Pipex, a network of pneumatic tubes that would shuttle important documents around San Francisco. It didn’t go anywhere.

But Pishevar has. Mention his name around Silicon Valley and you might get an eye roll. A fast talker and oversharer quick with hugs, tears and humble-brags, he drops the names of celebrity friends (Edward Norton, Sean Penn etc) likes dimes in a jukebox.

“He’s unquestionably a promoter,” says one Valley investor. “But there are many good things that come from being a promoter.” Ask anyone at Menlo Ventures, where Pishevar engineered one of the $4 billion venture firm’s greatest investments ever, in a then-small-but-growing taxi app called Uber.

Pishevar was initially turned down by Uber and its backers when it closed its second round of funding at the end of 2011. Pishevar was giving a talk in Algeria when he got a call from Uber CEO Travis Kalanick, saying he was back in if he could come meet Kalanick in Dublin. Pishevar grabbed the next flight to Ireland. “I didn’t really know Shervin, [but] I was getting e-mails from him and intros from everybody he knows,” Kalanick told Forbes in 2012. “I met with him because I had to.” The two hit it off, walking the streets of Dublin for hours. They signed a term sheet in the wee hours of the morning. Menlo left with an estimated 8 percent of Uber, at a valuation of $290 million.

The company is now worth $42 billion. “I always tell people ‘Lesson number one: Get on that plane,’” says Pishevar, whose Uber and other holdings are worth about $500 million. That score is the capstone of this immigrant’s rags-to-riches American dream. Pishevar was six when his mother fled post-revolution Iran in 1980, toting him and his two siblings. His father, who had run a big part of Iran’s TV network under the Shah, had barely escaped a year earlier and was driving a cab in Washington, DC. His mother, a teacher, got a job as a maid at a Ramada Inn. Pishevar’s English was so bad that his second-grade teacher threatened to hold him back. By the time he was 10, though, he was calling local radio stations and debating Middle Eastern politics. “I think he was born 40 years old,” says his brother Afshin, who sold his law firm to move to LA as Hyperloop’s general counsel.

After graduating from Berkeley in 1998, Pishevar returned to Maryland and started a series of companies, including an early operating system, WebOS, as well as the Social Gaming Network and Webs.com, which eventually sold to Vistaprint for $117.5 million. In 2007, he moved to San Francisco and began writing small cheques to startups on the side. Menlo Ventures hired him as an investing partner in June 2011, and he got the San Francisco firm into Tumblr, Warby Parker and Uber.

Two years ago, Pishevar raised $153 million to start his own fund, Sherpa Ventures, with former Goldman Sachs venture investor Scott Stanford. Rather than backing existing startups, their idea was to build new companies from scratch around talented people. One of the first ideas he put in motion: Hyperloop Tech.

The hyperloop startup has a typically Pishevar provenance. Over the past few years, he’s inserted himself in Hollywood’s self-important diplomat set, travelling with Sean Penn to Benghazi to meet Libyan rebels who fought Gaddafi and to Tahrir Square to rally with Egyptian protesters. In January 2012, he and Penn were riding on Elon Musk’s private jet to Cuba to pressure the Castro government to release some American prisoners. En route, Pishevar pushed Musk about when he was going to tackle the hyperloop, a project the billionaire had been dropping hints about for almost a year.

“He said he didn’t have time to do it himself. So I said, ‘I’ll do it. I’d love to do it.’ ” Over the next six months, Pishevar kept on Musk to publish his hyperloop research, but Musk kept begging off, saying he was too busy. Pishevar being Pishevar, he forced the issue: In May 2013, at the AllThingsD conference, Musk had again avoided the subject of the hyperloop onstage. So Pishevar got to the microphone first for the audience Q&A: “Elon, can you please let the audience know more about the hyperloop idea?” Suddenly on the spot, Musk stumbled through a description and reluctantly promised to release the report by August. The idea was now public.

And when he did release his report, the internet exploded with commentary, praise and snark. No matter, as Pishevar began putting the hype in hyperloop. A major Democratic Party donor, he turned a meeting with President Obama at the White House into a 30-minute hyperloop pitch. The President vowed to read Musk’s report that night, according to Pishevar, and the next week asked the Office of Science & Technology Policy to review the idea. He pulled a similar stunt on Larry Page while on the Google founder’s yacht as they watched the America’s Cup race in San Francisco Bay.

Pishevar’s persistence began paying off. Lonsdale committed to invest money and time. Then came Messina, who was already an outside partner at Sherpa Ventures. “Shervin understood very early on it was a political challenge,” says Messina. “But this is not a typical sell. It’s one of those things that if we do it, it could change everything. If we think on our feet and start moving fast, this is doable. It’s not like flying to Mars.” And when Musk came to Pishevar’s 40th birthday party on a private 850-acre island in the British Virgin Islands, the VC got his blessing to pursue David Sacks, who had been Musk’s COO at PayPal and had just sold Yammer to Microsoft for $1.2 billion.

“I thought I was being asked to join a charitable board,” says Sacks, who eventually joined Pishevar as Hyperloop Tech co-chair, “but I realised they were serious about turning this into a business.” While Musk was still officially keeping his distance from all hyperloop projects, he secretly met with Pishevar and Sacks for an update over dinner at the Sunset Tower Hotel in LA in April. “Elon felt that if we could prove it could work, even a two- or five-mile prototype, that would overcome any political challenges or regulatory issues,” says Sacks. “But we all agreed we had to prove it first with private money.”

That’s what Pishevar’s money is going towards. The $8.5 million will cover initial engineering and design, with the $80 million to build and operate the test track. But who will build it? Musk’s SpaceX engineers kept telling Pishevar the same name: Brogan.

As with his boss, it’s easy to poke fun of Brogan BamBrogan. The ridiculous name came when the former Kevin Brogan decided last year to merge more than just lives with his new wife, Bambi Liu, now Bambi BamBrogan. He’s got a Sgt Pepper’s-era handlebar moustache and deep v-neck T-shirt, which exposes a skeleton key. But get behind the pretension and you find a world-class engineer, who did all of the design work on the second-stage engine of the Falcon 1 and was the lead architect for the heat shield of the Dragon capsule. “He came up with a design no one had seen before,” says a former SpaceX colleague.

BamBrogan was initially uninterested in Musk’s idea. “I have no interest in helping rich people get from San Francisco to LA 20 minutes faster,” sniffs the well-paid engineer. But redrawing cities and the dirty container shipping industry, as Pishevar pitched it? BamBrogan was sold.

Dirk Ahlborn, a tall, easygoing German who bears more than a passing resemblance to Liam Neeson, comes to the world of transformative transportation theory through … pellet stoves. He had run an Italian company in that field, and helped launch an assortment of startups, including a gas-fuelled turbine play, after coming to Los Angeles in 2009. When the JOBS Act passed in 2012, he hatched a plan to make the startup process completely open source. His two-year-old Jump-StartFund encourages inventors to post their ideas and seek funding or partnerships from the public.

Musk’s white paper was pretty much a public pitch, and Ahlborn jumped on it. A partner introduced him to SpaceX CEO Gwynne Shotwell, and she gave the green light for HTT to call for proposals in October 2013. They quickly had a couple hundred volunteers to sort through.

Anyone who works at least ten hours a week gets equity in the company. Ahlborn, based out of Hermosa Beach, California, keeps the teams connected through weekly conference calls and shared Google Docs. “Some of them are reluctant to admit to their boss what they’re doing because they have full-time jobs,” he says. HTT has been refining aspects of the project for a year now, releasing its updates on its website. A group of math students at Harvard and other schools built a fairly advanced route-optimisation model that plans the cheapest and least nauseating path to link any city-pair. An electric motor company in Portland is working on the capsule’s propulsion system. A team of UCLA architecture students have created scale models of passenger interiors out of wood—but it’s not clear what they’re going to be doing once they’re done with school.

A cost analysis team estimates conservatively that a two-way passenger tube will run $45.3 million per mile. “I believe we’ll find innovations with steel or other materials to bring the price down closer to $20 million per mile,” says Jamen Koos, a Cisco employee who is running HTT’s product management team.

Ahlborn says he has interest from the Mexican government for a 120-mile loop connecting Mexico City to Queretaro, but he’s a long way from commitments. Even so, he’s convinced that his crowdsourcing model will not turn off potential customers. “Our 200 people, who know what they’re doing, are performing better than 30 people full-time,” says Ahlborn. Since August, work at Hyperloop Tech has moved from BamBrogan’s garage in LA’s hipster neighbourhood, Los Feliz, to a 6,500-square foot former ice factory in LA’s gentrifying arts district, just down the block from a topless bar.

A big breakthrough came following the Harry Reid meeting. The senator introduced the group to Anthony Marnell, who has built all of Steve Wynn’s Las Vegas megaproperties and also served as CEO of the Rio Hotel & Casino. His real passion? Returning passenger rail from the West Coast to Vegas. “I’ve been chasing fast trains around the world for almost 30 years,” he says. Over the past 10 years, Marnell and his investors have sunk $50 million of their own money into XpressWest, a proposed 190-mile high-speed link from Sin City to LA’s eastern exurbs, mostly to acquire the right-of-way. A hyperloop experiment would be far more interesting. Negotiations are ongoing. “There’s got to be a way for us to work together,” says Marnell.

A deal there would be important given that Musk’s original proposal—the SF to LA route—isn’t happening. Even discounting the political nuttiness that required 20 years just to get ground broken on California’s high-speed rail project, Musk couldn’t figure out a way to get tubes any closer than an hour from each city. Ramming rights-of-way through already congested cities remains a huge long-term issue with the project. HTT’s artist renderings show Hunger Games-style tubes on pylons crossing New York City’s East River in the shadow of the Brooklyn Bridge. Good luck with that. “I’m convinced hyperloop is doable if you ignore the rights-of-way issue —which you can’t,” says Justin Gray, an aerospace engineer at NASA Glenn Research Center in Cleveland. That’s part of why Hyperloop Tech is focusing on cargo: Since much of the eastbound cargo that goes into the port of Los Angeles travels via rail or road through Las Vegas, that route offers a natural test.

Those are just the beginning of the issues. On the technical side, the ride could be a barf rocket at Musk’s upper limit of 4.9 meters per second squared (or 0.5 g) of lateral acceleration. Japan’s Tokaido train tops out at 0.67 meters per second squared and goes only 180 miles an hour. You can also forget an entirely carbon-free loop. Musk envisioned lining the tube length with solar panels. According to BamBrogan, the drain from the hyperloop electric propulsion system exceeds what even that many panels could provide. There will need to be grid power, and that means coal.

The technical challenges are also steep. Hyperloop Tech’s capsule is designed to ride on a cushion of air pushed out through the sleds below the capsule. The harddrive industry offers some models, but no one has used air bearings that move at near transonic speeds outside of a lab. (BamBrogan’s team plans to build a test rig this summer in that area.) And they will have to build the equipment that will make the tubes themselves, since no such machine exists. “I need to hire people who are really good at figuring out what they don’t know,” says BamBrogan.

Such is life in a space race. Things that once seemed impossible have a way of getting done. Musk spent $100 million of his own money to build the Falcon 1 rocket, which failed four times before it worked. “It’s time to stop doing photo apps and start doing something for the planet,” says Hyperloop Tech board member Peter Diamandis.

Money won’t be an issue. Pishevar says once he gets liquid on his Uber stake (IPO, anyone?), he will personally fund half of Hyperloop Tech’s $80 million round. If they or any others show results, billions will flood in. “We’re looking at the end of one civilisation and the beginning of another,” says Pishevar. “There’s no turning back.”

First Published: Mar 10, 2015, 08:00

Subscribe Now