The largest American office of China’s largest bank sits on the 20th floor of Trump Tower, six levels below the desk where Donald Trump built an empire and wrested a presidency. It’s hard to get a glimpse inside. There do not appear to be any public photos of the office, the bank doesn’t welcome visitors, and a man guards the elevators downstairs—one of the perks of forking over an estimated $2 million a year for the space.

Trump Tower officially lists the tenant as the Industrial & Commercial Bank of China, but make no mistake who’s paying the rent: The Chinese government, which owns a majority of the company. And while the landlord is technically the Trump Organization, make no mistake who’s cashing those millions: The US president, who has placed day-to-day management with his sons but retains 100 percent ownership. This lease expires in October 2019, according to a debt prospectus obtained by

. So if you assume that the Trumps want to keep this lucrative tenant, then Eric Trump and Donald Trump Jr could well be negotiating right now over how many millions the Chinese government will pay the sitting president. Unless he has already taken care of it: In September 2015, then-candidate Trump boasted to

that he had “just renewed” the lease, around the time he was gearing up his campaign.

It’s a conflict of interest unprecedented in American history. But hardly unanticipated. The Founding Fathers specifically built this contingency into the Constitution through the Emoluments Clause, which prohibits US officials from accepting gifts, titles or ‘emoluments’ from foreign governments. In Federalist 75, Alexander Hamilton framed the threat thus: “An avaricious man might be tempted to betray the interests of the state to the acquisition of wealth.” Scholars have been debating what exactly constitutes an ‘emolument’ since the moment Trump won the election, and nearly 200 congressional Democrats sued the president over possible violations in June.

Much of the yammering in this area surrounds Trump’s hotels, especially the one in Washington, DC, which has billed $268,000 in hotel rooms and catering to the Saudi government, and his international licensing deals, which allow foreign tycoons and hucksters, many with connections to their local governments, to pay the Trump Organization more than $5 million a year in order to profit from the president’s name in far-flung locales.

But that’s all small potatoes. The real money in the Trump empire comes from commercial tenants like the Chinese bank. Forbes estimates these tenants pay a collective $175 million a year or so to the president. And they do so anonymously. Federal laws, drafted without envisioning a real estate billionaire as president, require Trump to publicly disclose the shell companies he owns—but not the hundreds of businesses pouring money into them or even the extent of the money involved.

“The public reading the [disclosure] form doesn’t know who is paying the president,” says Walter Shaub, who resigned as the federal government’s top ethics official in July. The president likes it that way. Neither the White House nor the Trump Organization would provide a list of the president’s tenants, much less reveal what they pay. Instead, Trump Organization lawyer Alan Garten provided a statement: “Following the election, the Trump Organization implemented a rigorous vetting process for all transactions, including leases, which includes a detailed review and approval by our chief compliance officer and outside ethics advisor.” In other words, government ethics officials, charged with detecting conflicts of interest, have never seen the president’s rent roll.

![g_103853_trump_tower_280x210.jpg g_103853_trump_tower_280x210.jpg]()

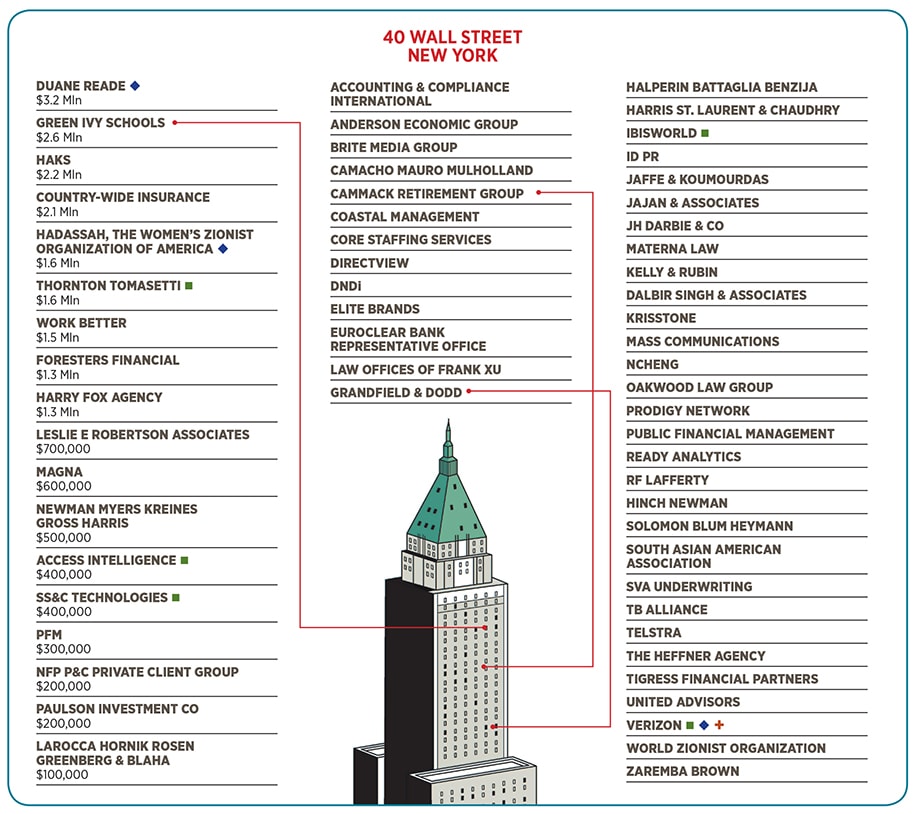

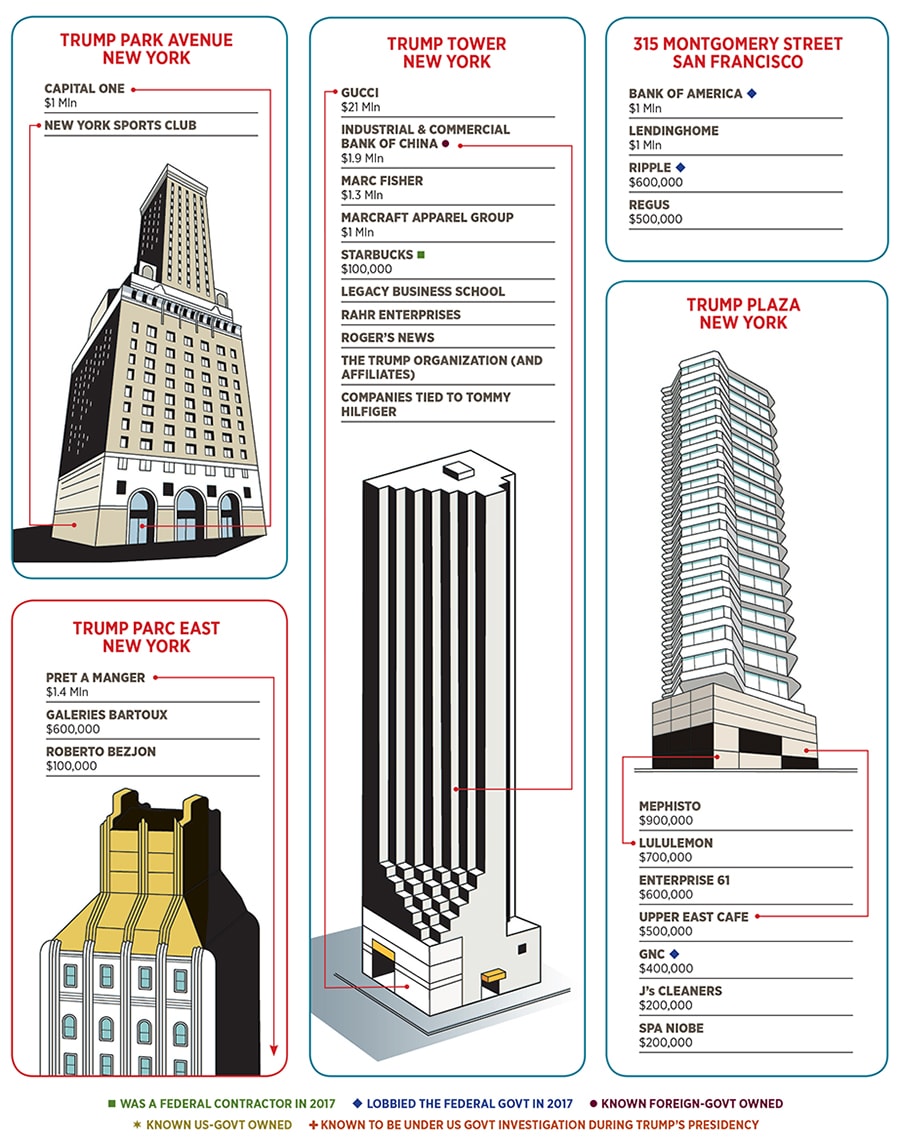

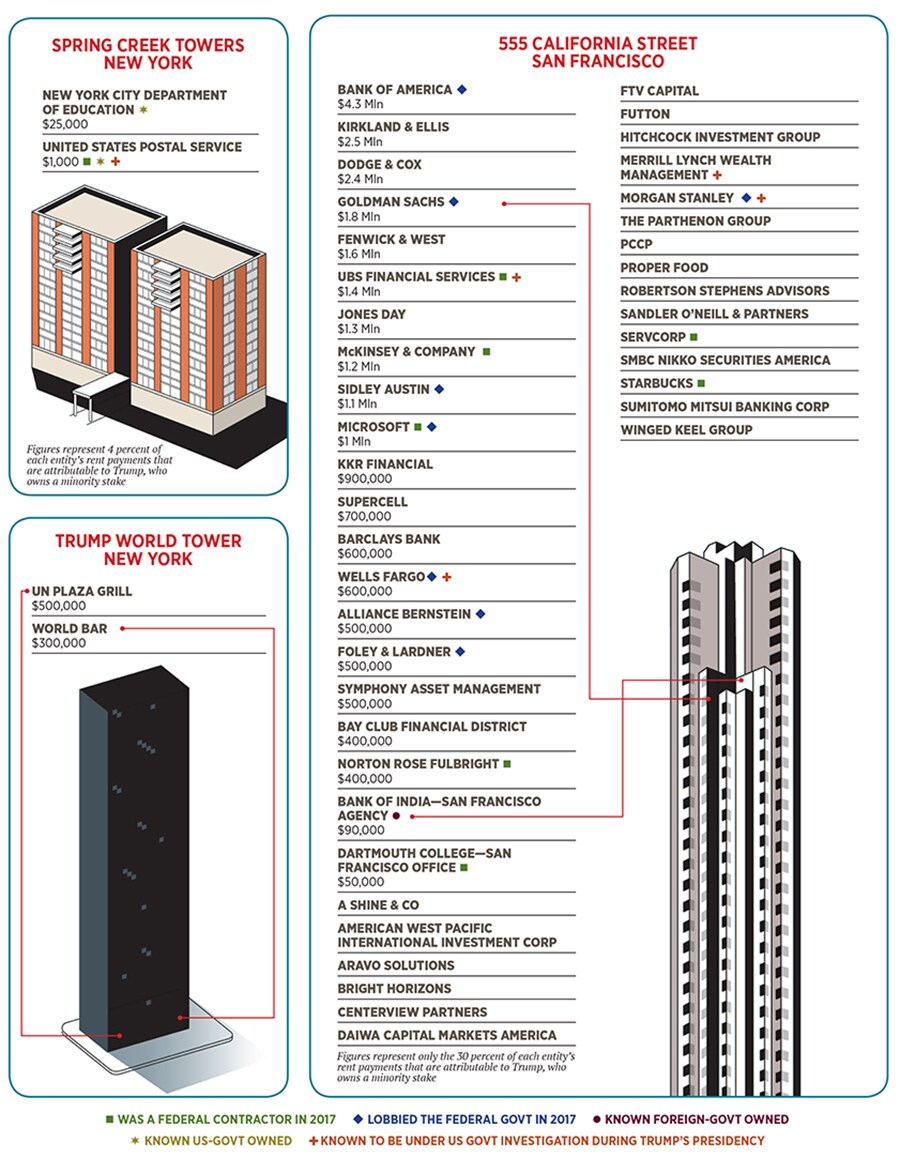

So we created one on our own, identifying 164 tenants, and then estimating payments, wherever possible, based on property records, debt prospectuses and conversations with real estate experts. When tenants refused to say how much space they rented, we made in-person visits and took rough measurements. (There were obstacles: The day after we sent questions to the Trump Organization, two guards kicked a Forbes reporter out of a shopping area of one Trump property.) When we could not get detailed information, we assumed tenants paid rates comparable to similar properties in their respective markets. We believe we’ve tracked the sources for 75 percent of the rent flowing into the president’s coffers. The numbers are significant. The names even more so: At least 36 Trump tenants have relationships with the federal government, from contractors to lobbying firms.

How tangled is it all? Forbes discovered one deal, previously unreported, in which Trump partially serves as his own landlord: The US government is paying some rent to the person who runs it.

Boiled down, the Trump Organization is more a collection of deals than an operating business. While Wal-Mart and General Motors rely on millions of customers around the world, the Trump Organization relies on a handful of large entities. That insulates the president’s business from consumer whims—and lagging favourability ratings—while leaving him vulnerable to corporate (or government) interests.

How, then, to consider the backroom discussions between federal officials and Walgreens Boots Alliance, one of the largest pharmacies in the world? Through its brand Duane Reade, it is the highest-paying tenant in Trump’s skyscraper at 40 Wall Street in New York, with $3.2 million in annual rent, according to a 2015 prospectus. In October 2015, Walgreens Boots Alliance announced a $9.4 billion merger with rival Rite Aid, requiring a sign-off from antimonopoly regulators. After the deal failed to secure approval under President Obama, it then fell to the Trump administration, which arrived in Washington during the first quarter of 2017. According to federal disclosures, that was the same quarter Walgreens Boots Alliance began directly lobbying the White House on “competition policy issues”. In September, despite objections by one of the two commissioners at the Federal Trade Commission, Trump’s tenant got the green light for a slimmed-down, $4.4 billion version of the deal. In January, Trump announced he would nominate the commissioner who supported the deal, Maureen Ohlhausen, to be a federal judge.

How much, if at all, did the business relationship affect the government’s decision? It’s inherently impossible to measure. Walgreens Boots Alliance says there was no connection whatsoever and that their lobbying was not specific to the deal. But even if Trump tried to rule without any personal favour, or if this was decided without his direct input, the appearance of a conflict of interest is unavoidable. The companies know their landlord is the president. And it’s hard to get into the heads of regulators, however well-intended or removed from the White House, who serve a president famously obsessed with personalloyalty.

![g_103855_trump_real_estate_280x210.jpg g_103855_trump_real_estate_280x210.jpg]()

Consider banks. Capital One rents space for an estimated $1 million at the bottom of Trump’s Park Avenue condo building—while the Justice and Treasury departments investigate the bank’s anti-money-laundering programme. Four years ago, the Department of Justice reached a nearly $17 billion settlement—the largest ever of its kind—with Bank of America, the biggest tenant (an estimated $18 million a year) at the 555 California Street complex in San Francisco, where Trump owns a 30 percent stake. Like all big banks, BofA remains under scrutiny by federal officials. In December, Trump tenants UBS, Barclays and JPMorgan, plus Trump lender Deutsche Bank, got waiver extensions from the Department of Labor that allow them to avoid part of their punishment for illegally manipulating interest rates and foreign exchange rates.

The overlapping interests stretch beyond the financial world. Take any hot-button issue of the past year, and there’s a good chance Trump’s tenants lobbied the federal government on it, either in support of, or in opposition to, the administration’s position. Nutritional-supplements giant GNC, which rents retail space from the president in New York City, advocated on health care reform. Nike, which pays an estimated $13 million in annual rent to Trump, spoke up on the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Starbucks, with locations in three Trump buildings, weighed in on immigration. Microsoft on net neutrality. Columbia University on the federal budget. There are even three law firms that are tenants and have lobbying divisions that push various client interests—while the firms pay the president a combined $4.1 million each year for rent.

The constitutional issues surrounding a landlord-in-chief transcend the foreign Emoluments Clause. Three months after Trump became president, the US Postal Service, part of the executive branch, started a new lease in a Brooklyn housing development where Trump owns a 4 percent stake, according to his financial-disclosure report. While he’s in the process of selling the stake—his lawyer Garten says that Trump’s business has no day-to-day control over properties where it holds minority investments—the president and his partners continue to collect an estimated $25,000 in annual rent from the federal government, whose founding charter, the Constitution, appears to prohibit the president from getting any government compensation except a salary.

Shortly before Trump’s inauguration, one of his lawyers, Sheri Dillon, stood inside Trump Tower with the soon-to-be commander-in-chief and revealed his plans to maintain his business interests while insulating his presidency from foreign influence. “President-elect Trump has decided,” the lawyer said, “that he is going to voluntarily donate all profits from foreign government payments made to his hotels to the US Treasury. This way, it is the American people who will profit.”

Left unsaid: The Trump Organization makes more money from the Chinese bank alone than it ever could expect from hotel visits by members of a foreign government. And the president has made no pledge to hand over that money. Or the incoming rent from the state-run Bank of India, which leases space in San Francisco, part of a deal that expires in 2019.

The point of anticorruption laws is to prevent the possibility of outside influence, so that no one has to wonder, after the fact, whether it happened. Yet one of the country’s primary conflict-of-interest laws doesn’t apply to the president.

By holding on to his assets, Trump has chosen to test whether the Emoluments Clause follows suit (he got one case dismissed in January two others are active). So the president remains in business with the world’s two most populous countries. Even if he tries to avoid a bias, there’s a clear feeling in foreign capitals that currying favour with his business can’t hurt. It’s a global perception problem, at best. “He does not forget his friends,” said Emin Agalarov, who helped broker the infamous Russia campaign meeting in Trump Tower, according to Donald Trump Jr. When President Trump announced a travel ban from seven Muslim-majority countries, it was hard to miss that the ban excluded Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Azerbaijan and the UAE—places where he had previously pursued business deals.

In the US, Trump’s foreign tenants, even ones without official government ties, can pose diplomatic complications. Gucci rents a Fifth Avenue retail space at Trump Tower for an estimated $21 million a year, paying the Trump Organization more than any other tenant in the president’s portfolio. That creates a potential headache with the Italian government, which is reportedly investigating whether Gucci dodged $1.5 billion in taxes. The company said it “is confident” about its operations. French insurance giant AXA pays an estimated $41 million to rent space in a New York skyscraper in which Trump holds a 30 percent interest. According to a prospectus filed in November, the French firm may have to disclose business with Iranian entities, which could open it up to US sanctions, at the discretion of the president of the US, who just so happens to take in an estimated $12 million from AXA each year. And so on.

Despite all this, Trump does not seem to think ongoing rental payments from foreign entities pose a problem. “No new foreign deals will be made during the duration of Trump’s presidency,” his lawyer said in that January press conference. Apparently, the Trump team defined “foreign deals” strictly as projects not on US soil, because one year later, with no fanfare, the signs in the windows of a couple of Trump properties revealed new tenants: Yoga retailer Lululemon and sandwich shop Pret A Manger, based in Canada and Great Britain, respectively.

It could soon get more complicated. Just around the corner from Trump Tower sits Niketown, which, after opposing Trump on the Trans-Pacific Partnership and NFL protests, announced it was leaving the building this spring, even though it still had years left on its lease. The roughly 65,000-square-feet space should command about $13 million in rent per year, and Donald Trump owns it debt-free. Whoever steps in has the chance to make annual payments to the president, at whatever price they want, and the public will have no foreseeable way to know how that compares with market rates.

The tragedy of this $175 million mess is that it was completely avoidable. Right after Trump was elected, most assumed he would divest his assets and engage in the biggest job in the world with clean hands. Since his company basically consists of assets and management deals, he could have set in motion a liquidation process. His iconic towers would still carry his name. And when he left office,

he could surely take that cash hoard to again buy properties or leverage his higher profile to yet more and better licensing deals. Shortly after the election, he tweeted: “Legal documents are being crafted which take me completely out of business operations. The Presidency is a far more important task!”

By “completely out”, the president meant letting his sons run it, and this creature of habit keeps his full ownership, along with the scores of payments that come with it. Among them: Rupert Murdoch’s media empire, which appears to be paying Trump $50,000 a year or so to lease an antenna atop a New York skyscraper and whose far-flung assets include the New York Post, a newspaper founded by the person who saw the problem coming two centuries ago, Alexander Hamilton.

With additional reporting by Deniz Çam, Angel Au-Yeung, Yinan Che and Humberto J Rocha

Image: Jamel Toppin for ForbesForget the international partnerships and the DC hotel. The surest way to put money into Donald Trump’s pocket is through his core real estate assets. More than 150 tenants—from foreign governments to big banks—throw him some $175 million a year without an accounting of who they are or how much they pay. Until now

Image: Jamel Toppin for ForbesForget the international partnerships and the DC hotel. The surest way to put money into Donald Trump’s pocket is through his core real estate assets. More than 150 tenants—from foreign governments to big banks—throw him some $175 million a year without an accounting of who they are or how much they pay. Until now