Duroflex: Bouncing back

Mattress maker Duroflex is regaining lost ground by ramping up product development, and expanding into new geographies

(Clockwise from top) Mathew Chandy, Mathew Joseph and Mathew George of mattress-makers Duroflex

(Clockwise from top) Mathew Chandy, Mathew Joseph and Mathew George of mattress-makers Duroflex

Image: Nishant Ratnakar

Mathew Chandy knows well the importance of having professionals in a family business. After all, the 42-year-old had already seen the flipside, quite early in his family business. A graduate of the National Law School of India University, Chandy was witness to his 57-year-old family venture, mattress maker Duroflex, reach soaring highs and brutal lows largely as a result of a family feud. Now, in firm control of the company, the former lawyer is en route to reclaiming what Duroflex had lost during the turbulent times.

“We lost about 10 years between the mid-1990s and 2000s,” says Chandy. “The opportunity cost was huge, and that’s actually when many of our rivals grew quite well. Over time, we realised that if we had to improve productivity and win the bigger battles, we had to bring in professionals.”

But, bringing in more professionals into a traditional, family-owned business is only one part of winning the battle. Since taking charge as the managing director of the Bengaluru-headquartered company in 2012, Chandy has digitised much of its operations, expanded into new geographies, ramped up its online presence, and is developing personalised products to give Duroflex a much-needed push in the Rs 10,000-crore mattress market in India. Over the next five years, he aims to be a Rs 2,000-crore company, from about Rs 500 crore at present.

India’s mattress industry is largely unorganised, with branded companies such as Duroflex, Kurl-on and Sleepwell controlling just about 30 percent of the market. “I am less focussed on the final turnover number,” Chandy says. “I have kept it flexible. But the focus is more on the vision and where we want to take Duroflex.”

As a result, unlike a decade ago, the mattress maker is visibly more aggressive in its approach, increasing its advertising spend and partnering with cricket teams Royal Challengers Bangalore and Chennai Super Kings in the Indian Premier League.

From Kerala’s hinterlands

Duroflex was set up in 1963 by Chandy’s grandfather PC Mathew, who hailed from a family of rubber planters. An engineer, Mathew had been working with the family’s tyre business, National Tyres, with an ambition to branch out and try his entrepreneurial skills.

Soon enough, he was selected for a government mission for entrepreneurs to Germany and Austria as the Indian government looked to kickstart the domestic manufacturing sector. Incidentally, he was joined by Ramesh Pai, a Mangaluru-based industrialist who would later go on to set up another mattress company, Kurl-on.

On the trip, while on a factory visit to Mercedes Benz, Mathew saw the use of rubberised coir in car seats, particularly due to its high durability and cushioning. This made the young engineer try his luck in setting up a similar business back in Kerala. He soon started Duroflex, with a manufacturing facility in Alappuzha. “But the machines were stuck with the Customs department, and he had to reverse engineer the entire process to get going,” Chandy says.

The company’s clientele soon included Indian Railways and bus makers, among others. “But, the business was still not profitable,” says Chandy. By the 1970s, Mathew’s older son, Chandy Mathew, who had graduated from the Indian Institute of Technology, Madras and the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, joined him. In the 1980s, the group expanded its business, setting up two factories in Hyderabad and Bengaluru. “Back then, Kurl-on and Duroflex were of the same size, and until the mid-1990s business was brisk,” adds Chandy, son of Chandy Mathew. The company also set up an export-oriented business based out of Kerala for organic latex, which had also emerged profitable.

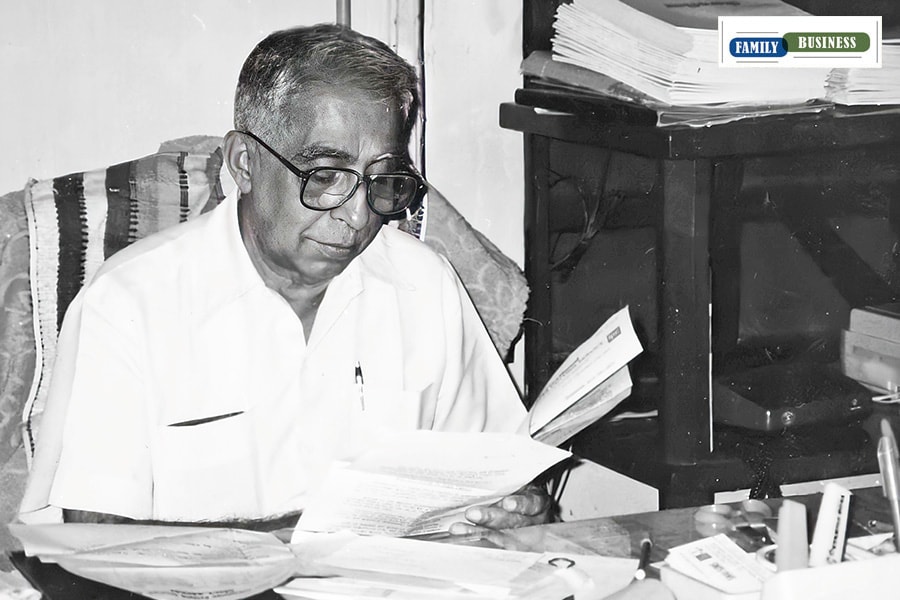

PC Mathew at his work desk in Alleppey, the first office where the Duroflex story began in 1963. The picture is from the early 1970s

PC Mathew at his work desk in Alleppey, the first office where the Duroflex story began in 1963. The picture is from the early 1970s

Yet, they were finding it difficult to expand further north, particularly because the industry had largely remained unorganised. The group also found it difficult to professionalise the business, with Mathew’s five other children joining it. Around then, the company also tried its luck in manufacturing coir as a substitute for wood, which wasn’t successful, laying the seeds of discord among the brothers. “It’s very important to have family constitutions and succession planning,” Chandy says. “Unlike in a family business, professionals are always judged based on their merit.”

Over the next few years, as the coir business failed to take off, the brothers too had a fallout, with three of them on one side and three on the other. “Over the next 10 years, Duroflex lost a lot of time as the board room battles intensified, and business decisions were stuck,” Chandy says. The dispute then went on to the National Company Law Tribunal, with three brothers leaving the company eventually. “That was the time when Kurl-on grew well,” Chandy says. “But, through it all, Duroflex focussed on setting global standards, but not many investments were made on growth.”

It wasn’t until 2008, when the family finally came together and worked on a settlement. But by then, unfortunately, Chandy’s father had passed away.

Picking up the pieces

Around the same time, Chandy’s uncle, George Mathew took over as the managing director. “He had been single-handedly running the business and had realised he needed to slow down,” says Chandy, who had been working as a lawyer with UBS in London. He was offered the role of running the business back home.

“Around 2012, my uncle had realised it was time for him to retire,” Chandy says. “We debated whether to sell or grow the business. I realised I wanted to be part of the India growth story.” It also helped that the global economy was in the midst of a slowdown, and India was largely immune to the crisis. That year, Duroflex had a revenue of Rs 110 crore.

Over the next year, after he shifted base to Bengaluru, Chandy spent much of his time trying to understand the family business, before revamping it. This included ramping up the marketing budget, focusing on new designs, upping the overall quality of products, and focusing on paying better salaries to employees in an attempt to professionalise the organisation and attract talent.

“Many family businesses believe the capital must be kept with them or in the business,” Chandy says. The company also brought on an advisor, Equitor Value Advisory, a firm specialising in unlocking the brand value of a company. “As opposed to a startup, we had to get an understanding of the brand and how we should get more out of it,” Chandy says. “We had to correct weaknesses and unlock the real value.”

Meanwhile, the company also started hiring more professionals. New recruits included Pradeep Mishra from United Breweries as CFO, Mohanraj Jagannivasan from Wipro to head sales, Mathew Thomas to head the polyurethane foam division, and Smita Murarka from Amante as head of marketing. Today, the company operates 500 exclusive outlets, with over 3,000 dealers and 10 company-owned stores around the country. It employs 1,500 people, including contractual and permanent ones, across five factories.

Over the next few months, the company is aiming to complete a manufacturing plant in Indore, which will help expand business in the western and northern parts of India. This will also need boosting its distribution network, and the affiliation with IPL has helped build brand identity. “We are no longer a regional brand,” says Chandy.

The big leap

When he had taken over the reins of the company, Duroflex sold its products only in the six states of southern India. Rival Kurl-on has over 10,000 dealers, and nine manufacturing facilities across Karnataka, Odisha, Madhya Pradesh, Uttaranchal and Gujarat. “Today, we have a network across 29 states, and over 30 percent of our business comes from non-southern markets. And that is only going to increase,” Chandy says.

Much of that, Chandy reckons is also thanks to its foray into the ecommerce sector in 2017, with the launch of Sleepyhead, a product aimed at millennials. It embodies the concept of a mattress in a box, which is logistics-friendly and can be compressed and rolled back, making it easy to ship. “Today, about 30 percent of our revenues come from ecommerce,” Chandy says. “We are trying not to be traditional anymore, and be as agile as possible.”

He was also helped by his cousins, who have since joined the business: Mathew Joseph leads the Sleepyhead business, while Mathew George heads new product development. “He is in charge of new materials, the new range of mattresses and design, including plans to create a work-from-home line of furniture,” Chandy says. Another cousin, Jacob George, working from Mumbai, is in charge of expanding Duroflex’s business in the western market.

“Between us, we have a pact to stick together and not fight,” Chandy says. “We will live with our differences and capitalise on them.” By 2018, consumer-focussed private equity (PE) fund Lighthouse invested $22 million (Rs 160 crore) in Duroflex. Lighthouse’s deal was the largest PE investment in a mattress maker after Motilal Oswal PE invested Rs 90 crore in Kurl-on, India’s largest mattress maker, in 2015.

“Unlike other FMCG products, this is a product that has a long lifespan,” says Devangshu Dutta, CEO of retail consultancy Third Eyesight. “But the industry has always remained unorganised.

Now, over the past decade, customers have become more conscious about their purchases and has moved towards branded products. The lockdown has only meant that people have also begun to focus more on their homes.”

That’s something Chandy knows well. Over the next few months, he wants to improve the conversation around the mattress category and has roped in celebrities including Milind

Soman and Anil Kumble to campaign for improved sleep and wellness. “What people don’t realise is how important sleep is to general wellness,” Chandy says. Besides, the company is also making inroads into the furniture category with products suitable for working from home, particularly for the millennial audience.

India’s mattress market is expected to grow into a $2.5 billion (Rs 18,300 crore) industry by 2022, according to a 2018 report from RedSeer Management Consulting. The branded mattress market is expected to constitute 37.5 percent of the market by 2022. “Unlike earlier, as a family, we are focussed on new channels and new geographies, and a focus on the future,” Chandy says. “In fact, August was among our best months.”

Certainly, Chandy and his cousins are only getting started.

First Published: Sep 24, 2020, 10:30

Subscribe Now