Can CEO Ken Frazier Reinstate Merck's Past Glory?

Ken Frazier, the pharma firm's CEO, could make it the world's greatest drug company again. But first, he needs to leave his own past behind

About nine months before Ken Frazier took over as chief executive of Merck in January 2011, he made a pilgrimage to see his old boss: P Roy Vagelos. When Vagelos ran Merck, it was the largest drug company on the planet, an innovative giant that created modern cholesterol drugs, blood pressure pills and the vaccine for chicken pox. He was a legend. Yet, Vagelos says no top executive had bothered to make the 24-minute drive to his office since he retired in 1994. “I’m the last senior executive who was hired by Roy Vagelos,” says Frazier. “It’s an honour, but it also imposes upon me an obliga-tion not only to think about his legacy but also about this company’s legacy.”

They had stayed in touch and both describe a quiet conversation over sandwiches about strategy and the future of the drug industry. Underneath the calm, Vagelos was jazzed. “He’s one of the best,” he says of Frazier. “His promotion to CEO a couple of years ago was really good news, because I was not elated with the previous leadership.”

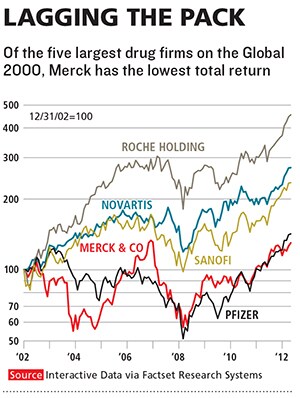

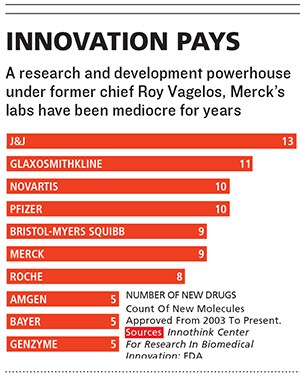

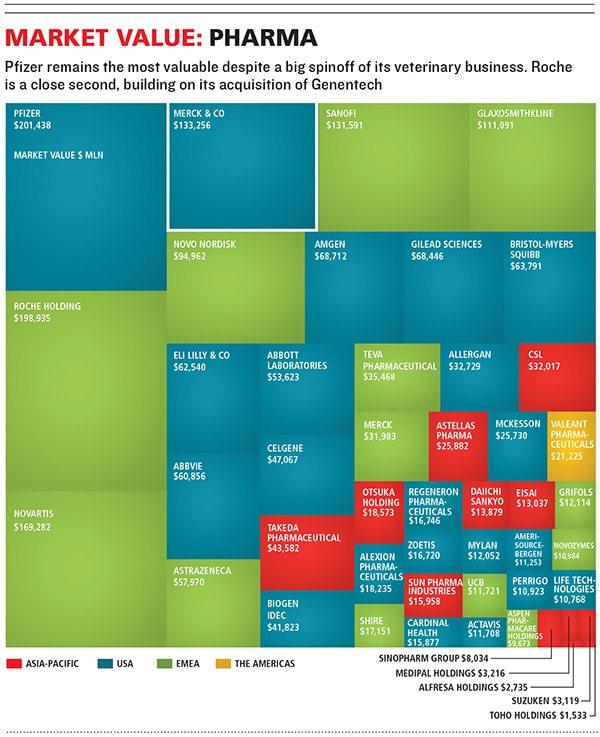

Merck, which has introduced more new medicines in the past 60 years than any other company, ranks only ï¬fth in new drug approvals over the past 10. Since 2003, the stock has been a yo-yo, and, excluding the $41 billion purchase of Schering-Plough, sales growth has been stagnant. Merck lags almost all of its competitors over the past one, ï¬ve and 10 years in the amount of money returned to shareholders, including both stock appreciation and dividends. It has not launched a drug that has reached annual sales of more than $1 billion since 2007.

Frazier, 58, may be better suited than anyone else to set things right. His understanding of Merck’s business comes from living with it for 35 years, ï¬rst as an outside attorney and then as the company’s general counsel and top marketer.

He professes a near-religious belief in letting his scientists do their jobs. And after a slow start, he’s begun to make real changes, the most important of which is replacing Merck’s longtime research and development head with Roger Perlmutter, a researcher who had left the Whitehouse Station, a New Jersey-based ï¬rm, in 2001 to run the labs at West Coast rival Amgen.But it is clear that Frazier still views himself through the prism of his lawyerly training—he has not yet grown into a commanding and decisive chief executive. He’s scrupulous about not making anyone else look bad and seems to be afraid to be seen as making too many big changes. “I am a person who does not subscribe to the hero-CEO school of thought,” he says. His persona is the culmination of the careful lessons he learnt from his long climb to the top and his masterful legal defence against the lawsuits related to the pain pill Vioxx, which saved Merck and got him the top job. In order to be a great leader, he’s going to have to unlearn them.

In an industry ruled by white men who are either scientists or salesmen, Frazier is an unlikely boss—not just a lawyer but an African-American who grew up in Philadelphia’s inner city. His father was a janitor with a limited education and, Frazier says, “one of the most intelligent men I’ve met in my life”. As a child, Ken idolised Thurgood Marshall and went to Penn State and then Harvard Law School, both on scholarship. Only then, he says, did he belatedly realise Harvard was “a factory to produce corporate lawyers”. Joining the law ï¬rm Drinker Biddle & Reath in Philadelphia in 1978, he was assigned as a ï¬rst-year lawyer to a case involving a subsidiary Merck no longer owns and begged his way onto the courtroom floor, where he notched up his ï¬rst legal victory on Merck’s behalf.

That case led to others, and eventually Frazier found himself repeatedly representing Merck and other drug companies. Many of those companies no longer exist, a lesson of which he remains painfully aware: “My job is to make sure that 10 and 15 years from now people aren’t going to say, ‘Oh, do you remember Merck?’ ”

Frazier believes that Merck’s main competitive advantage is the quality of its research, and he worships its researchers, who can spend 15 or more years developing a single new medicine.

“There was always something different about Merck,” Frazier says. “Now all drug companies have science, and all drug companies have production and manufacturing, and all drug companies have marketing and sales. But the emphasis is different in different companies. I fell in love with the science at Merck.”

In 1992, Frazier was hired as the general counsel of Astra Merck Group, a joint venture in charge of marketing the heartburn drug Prilosec. “He was always a superstar,” says Tony Coles, another African-American exec who was hired by Vagelos in the 1990s and is now chief executive of biotech ï¬rm Onyx Pharmaceuticals in south San Francisco. Vagelos brought Frazier in-house by making him head of public affairs in 1994, just before he was forced to take mandatory retirement. The board replaced him with an outsider: Ray Gilmartin, from syringemaker Becton Dickinson. Gilmartin made Frazier general counsel in 1999. “Just in time for Vioxx,” Frazier says.

Vioxx was an arthritis drug designed to be less harmful to the stomach than ibuprofen or aspirin. It also caused heart attacks. Critics said from the start that Merck should warn patients about that risk with prominent language on drug packaging and ads. Eric Topol, director of San Diego’s Scripps Translational Science Institute, calls Merck’s refusal to do that “a serious, prolonged problem about being honest about the risks”. If Merck had just listened, Vioxx might still be on the market.

In 2004, Frazier got a call from Merck’s head of R&D, Peter Kim, telling him that one of Merck’s own studies conï¬rmed that Vioxx was increasing heart attack and stroke rates. Together they called Gilmartin, and, after consulting with outside experts, the three of them decided to yank the drug.

Lawyers swarmed. Analysts estimated liability as high as $50 billion and pressured Merck to settle. But Frazier insisted on ï¬ghting every case, even after the controversy forced Gilmartin’s resignation.“The narrative that Merck sold a drug that it knew harmed patients is something that we would never do,” insists Frazier. The challenge, he says, was to explain the science to juries. “I knew that one of the truisms of the Bar—that you can’t try complex scientiï¬c cases to a lay jury—is false,” he recalls. “The problem was teaching our smart trial lawyers to take those cases and explain them in terms that the juries could understand.”

In the end, Merck won an impressive string of Vioxx cases and in 2007 reached a $4.85 billion settlement—less than 10 percent of the original estimates—with the bulk of the remaining plaintiffs.

Gilmartin’s successor, Richard Clark, a bearish and quiet Merck lifer, approached Frazier even before the Vioxx litigation ended to take over the company’s top marketing job. At ï¬rst, Frazier characteristically said no: “I need to ï¬nish this Vioxx thing. Because I’m a lawyer, and this is going to be my crowning achievement.” But Clark insisted, and suddenly in 2007, Frazier was in line to become Merck’s next CEO.

In 2006 and 2007, Merck launched the ï¬ve medicines that are still driving its earnings. Januvia, a diabetes pill in multiple forms, generates $5.7 billion in annual sales. Health care analytics ï¬rm EvaluatePharma predicts that sales will increase by 70 percent by 2018, making it the world’s bestselling drug. Also introduced: Gardasil, a vaccine that helps prevent cervical cancer (2012 sales: $1.6 billion) Isentress, a breakthrough HIV drug ($1.5 billion) shingles vaccine Zostavax ($651 million) and RotaTeq, an infant diarrhoea vaccine ($601 million).

But in 2007, Forbes broke the story that Merck and its partner, Schering-Plough, had been avoiding analysing the results of a trial of the cholesterol drug Vytorin. When results were ï¬nally released, they showed the pill was not preventing arteries from thickening any better than a cheap generic. Yale cardiologist Harlan Krumholz made a speech at a convention saying the drug might be “an expensive placebo”, and Merck shares dropped 15 percent the next day. (Full disclosure: Krumholz was a paid consultant for Vioxx plaintiffs and is a frequent Forbes contributor.) Prescriptions of Vytorin fell from 22 million in 2007 to fewer than 4.6 million in 2012, according to health care consultancy IMS Health. This February, Merck paid $688 million to settle a lawsuit with shareholders who alleged it had willfully withheld the bad clinical trial results. Frazier, ever the lawyer, denies any guilt.

The resulting drop in the share price of Schering-Plough had an upside. It meant Merck could buy the company cheaply ($41 billion in cash and stock) in a 2009 deal Frazier helped engineer. The deal nearly doubled Merck’s earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation, from $9.9 billion to $17.8 billion. To make the deal work, Merck has cut 29,000 jobs, a third of its workforce.

In the month Frazier became chief executive, the most promising drug from Schering-Plough ran into big problems. The pill was a blood thinner called vorapaxar, and it was supposed to prevent the blood clots that cause heart attacks and strokes. But it caused too much bleeding, crippling its commercial potential.

Then, in December 2012, a big trial of Merck’s heart drug Tredaptive showed it was ineffective and unsafe. It was supposed to be a gimme, a new version of niacin, a drug that had been used for 60 years to raise ‘good cholesterol’. Instead, it led to questions about whether so-called good cholesterol even prevents heart attacks.

Odanacatib, an osteoporosis drug, was the medicine Wall Street was most excited about. But in 2012, Merck disclosed there was a side effect but would not say what it was for fear of invalidating an ongoing study. This February, the company announced it would wait an extra year before filing it with the Food & Drug Administration, further spooking investors.

Sometime around the beginning of this year, Frazier says, he began searching for a new head of research and development. He claims that Merck research chief Peter Kim had always wanted a second act and had an exemplary 10-year career in a stressful job, and the decision to replace him was not brought on by performance. Others don’t see it that way. “I believe in Ken’s strategy,” says Kris Jenner, a biotechnology investor at Rock Springs Capital, a new investment fund in North Carolina. “He made a very difficult decision to have to make a change in R&D leadership. I agree with him that the status quo was not the path forward.”

One of Frazier’s first stops was a West Coast visit to Roger Perlmutter, who had the year before stepped down from Amgen and with whom he had worked in the 1990s. “You know, Roger and I talked about the kind of person that I was looking for, and I continued to meet other people, and we continued to talk. And over time as we boiled it down to the kind of person we were looking for, the person began to look a lot more like Roger.”

Perlmutter had left Merck in 2001. He’d wanted Merck to invest more quickly in protein drugs and to take other steps to streamline R&D. “My hair was on ï¬re,” says Perlmutter, 61. “I was sort of the angry young man, and I believed an enormous number of things needed to be changed.”

In the years since, Merck still has not launched a major protein drug, even as they became industry bestsellers. Frazier said Perlmutter’s experience building an R&D group from the ground up at Amgen was a key factor in the decision. Merck’s tradition is to pick an academic, but Frazier didn’t want one. “There are a lot of brilliant academicians,” he says, “but we also thought it would be helpful to have someone who had this kind of track record in industry.”

There are a few drugs in the near term that might give Frazier and Perlmutter a base to build on. Merck has asked the FDA to approve a new kind of sleeping pill that may be less likely to cause side effects than older drugs like Ambien. A new drug to reverse the anaesthetics used to paralyse patients during surgery, long delayed by the FDA, could also be approved this year. A promising cancer drug might generate investor excitement.

But despite Frazier’s oft-repeated enthusiasm for Merck’s R&D—“All I can do is create an environment where really talented, smart, committed people want to show up and [discover new drugs],” he proclaims—morale in the science trenches is very low. The frontline scientists are keenly aware of the ongoing layoffs and are understandably slow to trust Merck’s third new chief executive in 10 years. Hiring Perlmutter is a great start, but serious talent is also heading for the exits—including star cardiovascular researcher Andrew Plump.

“Frazier has talked about returning Merck to a culture of innovation but has made little progress,” says Bernard Munos, an analyst at Indianapolis-based InnoThink, a well-known pharmaceutical consultancy. “Perhaps he could not get his R&D chief to comply, or perhaps the inertia was too great. But that was a test of leadership that could have gone better.”

A bigger question is whether Frazier can face up to being wrong. Many of Merck’s experimental projects—such as another good cholesterol drug and a pill against Alzheimer’s—are in the absolute toughest areas in pharma. With Vioxx and Vytorin, sceptics felt Merck refused to engage with them, to its detriment. Defending both was Frazier’s responsibility. As chief executive, can he learn to listen? Or will he fall back on his trial lawyer’s instinct to dig in and ï¬ght? Krumholz, the Yale cardiologist, isn’t sure. “Merck’s a great company,” he says. “But they have yet to show the courage and insight to take the mistakes of the past and learn for the future.” Golden Years

Golden Years

P Roy Vagelos left Merck in 1994 because the board wouldn’t change the mandatory retirement age of 65—a decision he still calls “ridiculous”. Did he retire? No. In 1995, he became chairman of the board of Regeneron in Tarrytown, New York. It launched Eylea, a treatment for macular degeneration, in November 2011. In 2012, it sold $857 million of the drug and now has a market cap of $20 billion.

Regeneron isn’t Vagelos’ only second act. In 1996, he co-founded Theravance in South San Francisco. The company markets an antibiotic created by a retired Merck chemist, which was approved in November 2008, but investors are more excited about a new drug for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease being developed with GlaxoSmithKline. Theravance’s market cap: $2.3 billion.

—MH

First Published: May 09, 2013, 06:41

Subscribe Now