To stock or not to stock?

3D printing and the future of spare parts Industry

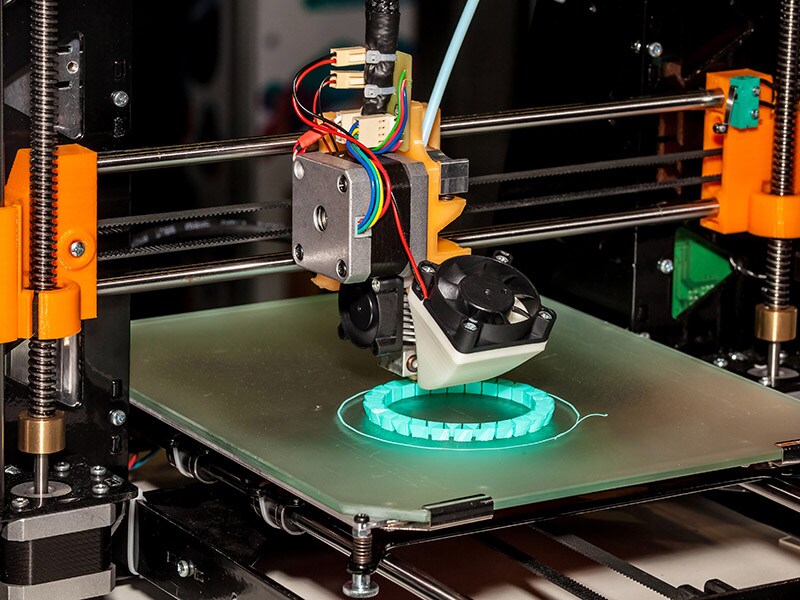

Image: Shutterstock[br]In a world where on-demand 3D printing is the norm, companies will face a choice between keeping spare parts on hand and printing them only when needed.

Image: Shutterstock[br]In a world where on-demand 3D printing is the norm, companies will face a choice between keeping spare parts on hand and printing them only when needed.

But it’s not as simple a choice as it might seem on the surface.

Jeannette Song, an operations professor at Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business, has created a mathematical model to help firms balance the costs of storing spare parts and the need to have them instantly available.

Parts suppliers know they need spares on hand in case something breaks. But no one knows what will break and when, so companies have to keep a wide variety of spare parts in inventory in large quantities. This, Song said, is expensive and inefficient.

“It takes up space and capital,” she said, “and there is the risk of spoilage and damage.”

The advent of 3D printing means manufacturers can print what they need when they need it, without holding massive inventory.

“But that means you don’t have what you need on hand exactly when you need it, because 3D printing takes time,” Song said. “So there’s a trade-off.”

Song found a hybrid approach – having some parts on hand and printing others when needed – works best. But knowing which parts to print and which to stock is the tricky part. That’s where her model steps in.

A paper describing the model, Stock or Print? Impact of 3D Printing on Spare Parts Industry, has been published in the journal Management Science. Song worked with Yue Zhang, who conducted the research while earning her Ph.D. at The Fuqua School of Business and is now an assistant professor at Pennsylvania State University.

The utility industry was the perfect proving ground because of its reliance on spare parts, both in quantity – a typical transformer can consist of up to 36 molded parts – and demand. When power fails or parts wear out, replacements are needed fast to maintain or restore service.

“For utilities, when you don’t have spare parts on hand, it’s a huge disruption,” Song said. “They have to have reliable and responsive supply of spare parts. Traditionally a firm in this position would have a huge warehouse in every market. But now 3D printing is a viable alternative, so you have two options.”

Song said a hybrid approach is optimal for most companies. Abandoning all spare parts inventory is too risky, but printing certain parts on demand can save a lot of money.

“If you are operating on a large scale, you still need to keep inventory on hand,” she said. “But a little flexibility goes a long way.”

For given circumstances, the model can calculate which spare parts a firm is likely to need more often and how many it should keep in stock, and which parts it can wait to print on demand – without diminishing its ability to function effectively.

“The big decision is how you rationalize all these parts, which ones to stock and which ones to print,” Song said. “In most cases we find a 3D printer would not be used very much at all, but the firm saves a massive amount of inventory.”

While 3D printing has not yet gone fully mainstream in the manufacturing industry, Song said firms are experimenting with it.

“It’s coming,” she said. “This, combined with AI, is going to be revolutionary.”

First Published: Jan 09, 2020, 17:03

Subscribe Now