The hills are alive with cheese

Amid the conifer-lined slopes, snow-drenched peaks and the glacial waters of Pahalgam, a Dutchman finds his home and life's calling

For a nibble on authentic Gouda, one of the oldest recorded cheeses still in production, a trip to the Dutch city of Gouda, after which the cheese is named, would be a good start. Gouda cheese was so named because it was historically traded in its namesake city, a practice that started in the Middle Ages when cities in Holland could procure certain feudal rights that granted them a monopoly on some goods. The city Gouda had obtained exclusive market rights for cheese. Even today, a traders’ market is held there every Thursday morning from June to August, when farmers from across the region gather to sell their cheese. Although most of the Dutch Gouda sold today is industrially produced, a few farmers still practise the traditional method of using unpasteurised milk.

However, a trip to the Dutch countryside is not on my itinerary. Far from it. I am 90-odd km away from Srinagar, en route to Pahalgam, the valley of shepherds. Picturesquely set at the confluence of the streams flowing from Sheshnag Lake and the Lidder River, Pahalgam, at an altitude of 2,130 metres, was once a humble shepherds’ village. These days, it is Kashmir’s premier resort where even during the height of summer the mercury hovers at around 25 degrees celsius.

Pahalgam is loved foremost for its mountains. Travellers from across the world arrive with backpacks and back pain relievers, eager to head out on the many trails crisscrossing the valley. Equine rides amid the conifers, snow-drenched peaks and the glacial waters of the Lidder River are tempting.

But I am here for a far higher purpose than to revel in the beauty of the landscape. Ensconced in a 4x4, with as many layers of clothes on me as wheels under me, I am headed towards Laganbal, a sleepy hamlet, just a bridge away from the bustle of Pahalgam. “Turn left at the end of the bridge and continue on the road and you will see a Land Rover parked by the side of the road. We’ll be waiting there. You can’t miss us,” are the directions I am given to get to my destination. With the last trickle of lukewarm coffee inside me, I wrap an extra scarf around my neck and prepare to meet the elusive cheese man of Kashmir.

Chris Zandee, true to his word, is waiting right beside the road, waving as he sees our vehicle. Behind him is a little signboard that simply states: ‘Himalayan Cheese’. After much searching, wondering and wandering, we have arrived at the Gouda cheese manufacturing facility in Pahalgam, Kashmir, started by the Dutchman along with the local Gujjar community.

“I didn’t come here looking to make cheese. That was incidental,” offers Zandee as an explanation to the ‘what are you doing here?’ written all over my face, even before we are properly settled at the table outside a modest-looking establishment, which, I am informed, is the cheese factory. Hardened cheese is left to soak in a brine solution till it sets

Hardened cheese is left to soak in a brine solution till it sets

The son of a farmer in Denmark, Zandee has a degree in automotive engineering and had been trotting across continents in the hope of doing something meaningful with his life.

He dragged himself across the length and breadth of India before finally feeling at home among the bucolic pine tree-lined slopes of Pahalgam. “The struggle for living and the challenges of life here grabbed my attention,” says 45-year-old Zandee, when asked why he chose Kashmir over the rest of the sub-continent. “I met my wife Kamala here and we decided to make this little plot of land home. As a foreigner, I can’t own land in India. And even though my wife is Indian by lineage (she grew up in Malaysia), she too can’t own land here. We have rented this plot. But the law permits us to operate a business here. And so while the house isn’t owned by us, the business is,” he explains.

As I look around and point to what I assume is a greenhouse, I hear a chuckle from behind. “It’s an earthquake resistant structure,” I am proudly informed by a tall, dark and shy Gulaam Hassan, the 48-year-old general manager of Himalayan Cheese that employs three Gujjars, including Hassan’s son Shabbir, as full-time staff to run the day-to-day operations, from cheese-making to book-keeping to sales.

It took a year of training to go from a picture-book type of handmade manual, with step-by-step instructions on how to make the cheese, to using calculators and keeping records of milk supply. “Basically, when this business is profitable and we want to move on, we are confident that we would have entrusted it in capable hands empowered with enough knowledge and skill to run the business successfully and continue to add value and make a difference to the community,” says Zandee.

When he first came to Kashmir, all he wanted was to use his skills and resources to be useful to the local community and to make a contribution to the economy, which is tourism-centric. Someone offered him some cheese-making material that was lying around and “my wife and I spent 10 days on the mountains by the side of a creek trying to make cheese. It was an epic fail—cheese can’t be made outdoors in the rain. It has to be made indoors. But that we could make cheese and it could be a viable business—that was the learning we came back with,” he says.

And just then, as if on cue, Shabbir emerges from the mud hut with a tray laden with cubes of yellow Gouda. He has several varieties of it: Walnut, cumin, mustard, black pepper, chilli, fenugreek and more.

Sitting there, listening to Zandee narrate his tale, with the icy waters of the Lidder racing past in the distance, the pine-dotted mountains and the sun playing hide and seek, it seems almost surreal to be spending a Sunday morning in the Himalayas tasting cheese. Suddenly, the long, cold drive from Srinagar in the wee hours of the morning seem worthwhile.

With a climate suited to cultivate a variety of food products, Pahalgam already has plenty of farm produce that goes well with cheese, like apples. Milk, the main ingredient for making cheese, is available in plenty thanks to the Gujjars. They are the shepherds of the valley who herd their stock of dairy cattle and move up and down the mountains of Kashmir flitting between altitudes according to the weather.

Pahalgam is a convenient mid-way stop en route to the cooler climes of Ladakh during the summer months and on the way back to the warmth of the valleys of Kashmir for the winter. While generations of Gujjars have spent lifetimes grazing their cattle on the fertile slopes of Pahalgam, they are “not Kashmiri. And thus, not accepted as part of the Kashmiri milieu,” says Zandee. “In Holland, I had never experienced caste. Class? Yes, but never caste. And as much as I wished to immediately eradicate this horrible inferiority complex that the Gujjars inherently had and make every one of them feel like an equal in society, that was just wishful thinking. I couldn’t change overnight something that was created over centuries.”But the Gujjars had a precious commodity that would make them equal partners in Zandee’s business: Milk. And with this, they could be prosperous. The gap between them and the high-class Kashmiris could also be narrowed. “My wife and I had found purpose and meaning. And a business and a home… with a view,” says Zandee.

With a notebook filled with the names of more than 150 Gujjar milk suppliers, he explains how the foundation of his business was laid. Milk supply is never constant it depends on foddering, the weather, the cattle’s health, the antibiotics administered and many other such factors. Zandee has three different milk suppliers to make up for any shortfall from a single source.

Before he arrived on the scene, the Gujjars would sell their milk in the Pahalgam market to suppliers who would arbitrarily fix prices. They had no alternative but to accept the quoted amount.

“For me, fair trade is the only way. Whether I manage to sell the cheese or not is my problem, not the Gujjars. It took them a while to trust me when I proposed to pay them a fair price. But today, because of fair trade, even the milk suppliers have started to pay them decent prices. We believe in our product and in contributing back to the society we are part of. As for Hassan and the other employees of Himalayan Cheese, they are now looked up to not only by hundreds of other Gujjars but also by the Kashmiris for effectively running a business and that too based on the values of fair trade, where the benefits are shared by all,” he says.

Zandee has also helped local Gujjars increase milk production during the winter lull and maintain herd hygiene.

For all the fanfare surrounding it, cheese is a humble and earthy food. And unlike other domestic stock that requires lush pastures, the cattle of the Gujjars are not too demanding. They are content with the limited herbage at their feet, or whatever else is at hand (as I found out when one tried to eat my scarf).

The milk is collected daily by Zandee, or one of his staff, from a pre-designated spot and transported back to the workshop-cum-home of the Zandee family. There, it is carefully checked and measured for fat to ensure that the final product will be of a good quality. Many of the Gujjars also use leftover milk to make kalari or maish krej, a traditional cheese often referred to as Kashmiri mozzarella. Hassan steps in to ask if we would like to taste some. An offer I cannot refuse.

While Zandee describes how the milk is filtered, heated, cooled, becomes yoghurt, and how the curd is separated from the whey, Hassan is back with a steaming plate of kalari and some coriander and chilly chutney. “Once the whey is removed, the curd is then curdled and at this point, we add different spices or nuts to the mix,” Zandee explains as I bite into the kalari. Fresh, moist and mildly sour, it has a bit of a squeaky bite to it.

“When Himalayan Cheese sells kalari, we are taxed 13.5 percent but if a Gujjar makes it, it is not taxed. I could easily have sold it as Gujjar produce and avoided tax. But then, if all I really wanted was to run a business, I could have made cheese in Delhi or Mumbai or Holland. I believe that better business ethics bring more business mileage,” says Zandee.

We move to the inside of the ‘factory’ where Hassan takes over the narrative of the cheese-making process, pointing to the moulds where the curds mixed with spices are placed to drain, set and harden. Next in the process is placing the hardened cheese into a brine solution till it sets. It is then removed, covered and allowed to sit so that it can age.

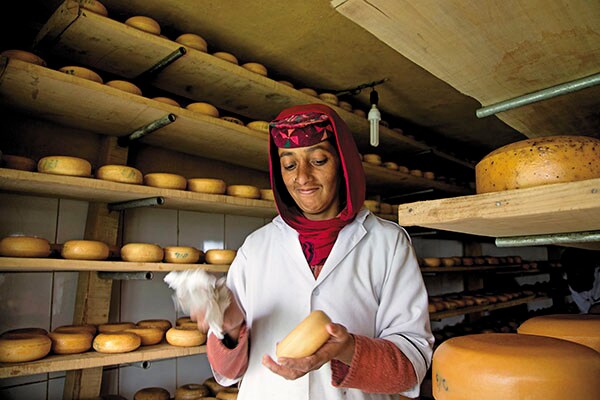

As we step into the basement, we are greeted by rows upon rows of shiny wheels of cheese. Each wheel is carefully waxed daily and meticulously catalogued and dated. Waxing is the traditional method of sealing a cheese for ageing. (Wax insulates the cheese from oxygen, while keeping it from drying out during the ageing process.)

A tempting array: Zandee makes several varieties of Gouda with walnut, mustard, cumin, black pepper and fenugreek

Armed with Gouda wheels of different flavours, I prepare to take my leave. But Zandee offers to drive me up to Pahalgam where the driver is waiting for me. Though I had initially planned to walk the approximately 3.5 km route to the rendezvous spot, I consider the weight of the Gouda, and gratefully accept his offer.

At the tourist checkpoint, near the entry to Pahalgam, an armed guard stops the vehicle. “Toll please,” he requests. Zandee greets him with a “Salam alaikum” and rattles off in Gojri (the Gujjar dialect) that he is a local and is not going to pay toll. Taken aback, the guard hesitates. Zandee laughs and steps on the pedal. “Every few weeks they have a new guard here and it takes the new guy a few days to realise that I’m more local than the Kashmiris who come here for an afternoon picnic.”

Later in the day, on the drive back to Srinagar, I am humbled all over again by the beauty of the landscape and the unique way of life that I have just experienced. As the sky darkens and raindrops blur the view, I strain to catch the faint outline of the Lidder, thinking about a Dutchman and his quest to find meaning and how the means followed.

I tear open the brown paper package wrapping from a slice of walnut Gouda and bite into it. Since it is difficult to get alcohol in Pahalgam and most of Kashmir, a wine pairing with Gouda is impossible. Fortunately, it pairs marvellously with a mountain-view and plateful of apples.

First Published: Dec 17, 2015, 07:46

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Sep 10, 2010 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)