Adrenaline: The rush factor

The mechanics behind the excitement elixir, adrenaline

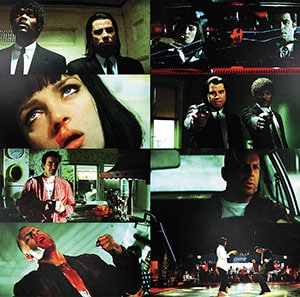

You take off the shirt and find the heart,” is one of many unforgettable lines in Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction. It is voiced during a scene in which hit man John Travolta and a drug dealer grapple with how to revive Uma Thurman who’s lying unconscious after having mistakenly snorted heroin instead of cocaine. There’s dried blood in her nose and she has stopped breathing. In desperation, Travolta slams a syringe full of adrenaline straight into her heart. Like Lazarus rising from the dead, Thurman wakes up, gasping for breath.

Ever since its discovery and isolation—the process spanning over a century of research—adrenaline has been accorded preternatural powers. The hormone, which the body secretes in times of intense fear, anger or stress, can resuscitate, revitalise and revive the heart. Or so popular culture would have us believe. It has become part of our emotional lexicon, and reduced to a cliché: Seek an ‘adrenaline rush’ crave an ‘adrenaline high’ experience life in high definition with a ‘shot of adrenaline’ hooked to fear-fuelled thrills like an ‘adrenaline junkie’.And John Travolta can revive Uma Thurman’s heart—but only in Hollywood.

In his book, Adrenaline, Brian B Hoffman, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, uses this classic scene from Pulp Fiction to shatter the “wildly implausible medical scenarios” surrounding the hormone. “Adrenaline alone does not generally restore the circulation without additional interventions,” he says. A combination of mechanical chest compressions (think David Hasselhoff in Baywatch), electric shots and adrenaline is used to resuscitate a person’s heart.

Adrenaline has been accorded preternatural powers. Like in Pulp Fiction, John Travolta could revive Uma Thurman’s heart by injecting the hormone

In the initial years after its isolation, the medical community viewed adrenaline, also called epinephrine, as a miracle hormone, one that had the power to bring the dead back to life and cure bedwetting. It didn’t take long, however, for its magical powers to be called into question. Hoffman mentions how Franklin Roosevelt’s doctor injected adrenaline straight into the US president’s heart when he suffered a cardiac arrest in 1945. It didn’t help.

But what are the mechanics behind this excitement elixir called adrenaline? For starters, as its name indicates, the action takes place near the kidneys, the renal organs. What happens is that in times of extreme stress—before an exam or if a T.Rex has you in its line of sight or when the stock market is misbehaving—the brain releases a chemical message and a nerve impulse: The messengers or hormones go through the blood to the adrenal glands as does a nerve impulse through the spinal cord, but to another part. In response, the glands release adrenaline and another lesser-known hormone called noradrenaline—yes, someone had a weird sense of humour—into the blood. Simultaneously, noradrenaline is released in the brain. The stress hormone cortisol is added to this brew.

With all this neural activity and hormone secretion, the entire body responds at warp speed. In the liver, cells break down glycogen and release more glucose into the blood. Blood from the stomach is diverted to the heart, brain, lungs and muscles, which explains why we are both mentally alert and physically charged. The heart beats harder and faster. You can hear it thud. Airways in the lungs widen and oxygen flows faster into the blood. Blood pressure rises. Blood sugar increases. Muscles tense up. Hair on your skin stands at attention. Pupils dilate. Pain is suppressed. And you respond. You become the very best you can possibly be. You run faster, fight harder, than you ever have before.

Just don’t expect any miracles. If you’re being chased by a cheetah, and the only time you’ve ever run in your life is to grab the last breakfast donut on a cafeteria counter, you’re still going to be the cheetah’s dinner. In his book, Extreme Fear, The Science of Your Mind in Danger, science writer Jeff Wise shows how the right dose of fear can help us discover our inner hero. “When we find ourselves under intense pressure, fear unleashes reserves of energy that normally remain inaccessible. We become, in effect, superhuman,” he writes. Our Spidey senses don’t just tingle, they’re on overdrive. But he adds a caveat. “There’s a limit to how fast and how strong fear can make us.”

In popular culture, adrenaline’s exaggerated avatar fuels our imagination. Jack Bauer in 24 and Walter White in Breaking Bad have the world in the throes of adrenaline-fuelled speculation. Shakespeare used it with discretion. Alfred Hitchcock capitalised on it in his films. He once said, “I am scared easily, here is a list of my adrenaline production: 1) small children, 2) policemen, 3) high places, 4) that my next movie will not be as good as the last one.”

Hoffman uses The Incredible Hulk to break down the movement of adrenaline. Bruce Banner is no ordinary human being. The secretion of hormones is amplified in his body, and “triggers the complex chemical-extraphysical process that transforms him into the Hulk”. The time taken for Banner to shred his purple pants and morph into a green mass of muscle is anywhere between a few seconds to five minutes.

In real life, adrenaline is essential to our survival. It spurs our flight or fight response. The phrase ‘fight or flight’ was coined by American physiologist, Walter Cannon, in the 190s. But two scientists—John Abel at John Hopkins University in Baltimore and Jokichi Takamine who was working independently out of a private laboratory in New York—isolated the hormone. In 1900, Takamine extracted adrenaline from the glands of sheep and oxen, and applied for a patent.

Today, adrenaline is available in injections and is used to treat life-threatening allergic reactions because epinephrine stimulates the heart, improves breathing, and can increase blood pressure. In hospitals, doctors sometimes administer it when a patient is suffering a cardiac arrest.

It is such a complex hormone that scientific breakthroughs are still taking place. It appears that adrenaline can cause death by broken heart. Some people, especially the elderly, are prone to a heart condition called Takotsubo cardiomyopathy or ‘broken heart syndrome’—a reversible condition where the heart muscles are weakened. In 2012, researchers at London’s Imperial College said that adrenaline could be the reason behind why people with this condition die barely a few days after they suffer the loss of a loved one. When the body is forced to confront such an intense shock, it releases huge amounts of adrenaline. For a person with broken heart syndrome, the heart muscles are overwhelmed by this massive dose, and adrenaline shuts down the organ instead of strengthening it.

Early humans who depended on their instinct to survive may have experienced the same rush that we face today, almost 300,000 years later. But the human body cannot sustain adrenaline for extended periods of time, which could explain why we are addicted to the heady feeling it gives us. Adrenaline allows us a moment where we can be heroes.

First Published: Jun 27, 2014, 06:30

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Jan 08, 2010 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)