Inside Jordan's city of mosaics

The intricate mosaics inside an ancient church in Madaba, Jordan, depict a history rich in religion and harmony

Image: Shutterstock

From the outside, the Greek Orthodox Church of St George looks unassuming: A simple structure of brown brick, set away from the main road. It is a dull and rainy morning in Madaba, and visitors are thin on the ground, even though it is peak tourist season in Jordan.

Those adventurous travellers—largely from Western Europe—who have made their way to Jordan in early winter have barely touched down into the capital city of Amman before impatiently heading down south to the country’s biggest attraction, the ancient city of Petra, a Unesco world heritage site, about 250 km away.

An entire city hewn out of sheer rock by the local Nabataean clan over 2,000 years ago, much of it remains a mystery to archaeologists and historians even today.

But Madaba lies on the way, just 30 km from Amman, and right along the road known, somewhat grandly, as King’s Highway. Although guides and guidebooks claim that the original route can be traced back to more than 5,000 years, today the highway is as modern as it gets, taking us to ancient sites around Madaba, where Moses and even Jesus are believed to have once walked. The Greek Orthodox Church of St George has an unassuming exterior, but is the tourism highlight of Madaba

The Greek Orthodox Church of St George has an unassuming exterior, but is the tourism highlight of Madaba

Image: Charukesi RamaduraiMy interest in the region lies not so much in its religious history as in its cultural heritage—although in this part of the world, it is decidedly tough, indeed impossible, to draw a line separating the two. But our clear focus did help us ignore the holy attractions of the Jordan River (where Jesus was purportedly baptised) and Mount Nebo (where Moses was said to have first caught a glimpse of the Promised Land) without any qualms. Madaba, today, is a predominantly Muslim nation with a thriving Christian population, and is known for its religious harmony.

The region of Madaba is believed to have been inhabited for over 4,500 years, finding a mention in the Biblical tale of the Exodus. It became a prosperous town with modern infrastructure under Roman rule in 106 AD, which continued till the Christian Byzantine era (4th century AD onwards), when most of the churches in the area were built (and the mosaics created).

Following an earthquake that ravaged Madaba in 747 AD, the town was abandoned for over a millennium. It was populated again only around 1880 AD, when about 2,000 Christians from Karak (120 km from Amman) made it their home, after a dispute with local Muslims in their town. It was only when they began digging around Madaba to lay the foundations of their homes and churches that the ancient old city’s mosaics began to emerge.

So, more than anything else, it is really the story of Madaba’s mosaics that has drawn us here.

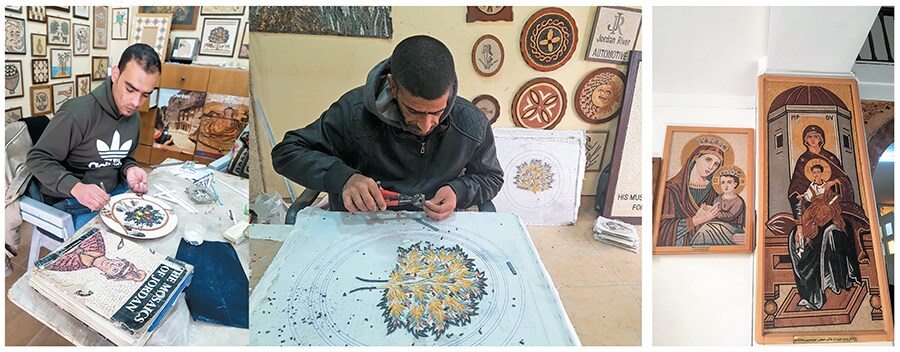

With hundreds of floor mosaics uncovered in the last century or so all over town, in its churches and private residences, Madaba has come to be known as Jordan’s City of Mosaics.  From left: The mosaic workshops inside Madaba town welcome visitors to watch the process several such mosaics of the Virgin Mary with baby Jesus adorn the walls of the St George Church

From left: The mosaic workshops inside Madaba town welcome visitors to watch the process several such mosaics of the Virgin Mary with baby Jesus adorn the walls of the St George Church

Image: Charukesi Ramadurai

These mosaics range from fragments dating back to the 1st century BC, found in the hill fortress at nearby Mukawir, to complete patterns from the Byzantine era. In case of Madaba, the raw materials were, and still are, available in plentiful in the form of sandstone from the surrounding hills. Rich in natural minerals, they contain a multitude of hues, ranging from deep browns to rich yellows and vivid reds.

After a bit of research, I learn that mosaic art has a long and rich history, dating back to 8th century BC in Mesopotamia, spreading to ancient Greece and Rome in the Classical era. Mosaic images are made by putting together small bits of naturally coloured stone or glass, with some form of adhesive, onto a pattern sketched on a flat surface, usually the floor. The art soon found favour on walls and ceilings, especially in places of Christian worship, before fresco painting replaced it during the Renaissance of the early 15th century.

This art form also flourished in the Byzantine Empire—whose capital city and cultural hub was Constantinople (modern day Istanbul)—and lasted for over nine centuries, from roughly 600 AD. Around this time, it also found its way into Islamic art, including religious structures such as the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, and the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus.

*****

We set off from Amman early in the morning, and pull up an hour later at the Tourist Information Centre in Madaba. The two employees here—helpful, but speaking only Arabic—thrust a map into my hands, circling the significant sites, and underlining the Byzantine Church of St George for good measure.

Yes, of course, the church, with its mosaic map, is the local superstar, but the Madaba Archaeological Park is right around the corner, and that is where we begin our walk. The morning rain has let up by now, and the sun has come out, shining gloriously. This carefully restored site also houses the 6th century Church of the Virgin Mary and has excellent signboards in English all over to make our life easier. The church was unearthed in 1887 beneath the floor of a private residence, with its original floor mosaics more or less intact. A mosaic on the open gallery at the Madaba Archaeological Park

A mosaic on the open gallery at the Madaba Archaeological Park

Image: Charukesi RamaduraiWe enter this archaeological site not quite knowing what to expect it turns out to be an impressive open-air museum filled with brilliant mosaics from several centuries ago, with much of the colours still intact. The outer gallery is a collection pieced together and mounted on the walls. The room at the centre—I begin to think of it as the inner sanctum, given the magnificence of the massive floor mosaic gleaming in the morning sunlight pouring in through the arched windows—is an ode to geometry, design and art. The four seasons, various gods and goddesses of the times, flora and fauna… there seems to be no theme that is not depicted in natural colours on these cracked floors.

From here, we walk slowly towards St George’s Church, stopping to peer into the workshops all along the way that have opened their shutters for business. Although, technically, these are stores that sell mosaics to tourists, most of them are also happy to demonstrate how they are created.

But first, the church.

The interiors of St George are predictably impressive. The few tourist groups are here to see the mosaic map in front of the altar, cordoned off on one side to prevent people from walking over it.

The mosaic map was discovered in 1884 during the excavation for the later Greek Orthodox Church of St George, which was built on the site of the ruins of an old Byzantine Cathedral dating back to the 6th century. (Five more churches and private residences rich with mosaic art were found soon after.) The mosaic map

The mosaic map

Image: ShutterstockThe map, uncovered in the midst of ruin and rubble, highlights all the significant Biblical sites in the region, from the Nile Delta in Egypt to Lebanon, and is known to be the only such map in existence. Believed to have been created around 560 AD, this colourful and sprawling—originally almost 16 m long and 6 m wide—mosaic map was made of more than 2 million bits of stone. Even though it is badly damaged, with only a quarter of the original surviving today, this map, with its complete layout of Palestine, provides unparalleled insights into the complex evolution of the troubled region.

I move in for a closer look, eager particularly to see Jerusalem in all its detail—the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the Damascus Gate and the Tower of David, all clearly visible. There is no definite understanding today on why this map was created or by whom. One of the main theories propounded by historians and religious theologians is that it was meant to be a visual representation of the Promised Land as seen by Moses from neighbouring Mount Nebo.

Apart from the floor map, around the church every pillar has, what looks like from a distance, a painting in vibrant oils—more of the marvellous mosaic art—of Mother Mary with baby Jesus in her arms. And in a gesture that left me moved, one typical to this region, the captions under each of these are written in Arabic.

*****

Back out in the streets, we have just enough time to stop at a couple of mosaic shops before heading down south in time to catch the ‘Petra by night’ experience. At most of these workshops that sell souvenirs in the form of coasters, fridge magnets, table ornaments and decorative wall hangings, modern motifs ranging from Michael Jackson (‘His Music Will Never Fade’ states a unique rendition of the famous moon-walking musician) to various versions of Yin and Yang in classic black-and-white have found a place on the walls. Yet, the Tree of Life remains the most popular theme in Jordanian mosaics, harking back to the Biblical tree in the Garden of Eden whose fruit promised eternal life.

At both the shops we wander into, the artists are working on this very motif. At the first one, the current owner Ahmed—in his late 30s, he has inherited the shop from his father—passes around his precious, tattered book The Mosaics of Jordan for a look. It is his source of inspiration for both new and old designs. And as he works with ease, he explains the process to us. This, it turns out, is exactly how it has been done for decades, before him by his father and grandfather. He laughs when I ask him if he has made any changes to keep pace with modern times.

One thousand years ago, they knew what they were doing, he says.

As I walk out of his shop clutching my Madaba souvenir—a small Tree of Life table mat—I can only agree with Ahmed. Why mess with something that is already perfect?

First Published: Mar 11, 2018, 06:47

Subscribe Now