Rehabilitation saves not just elephants, but humans as well: WTI founder

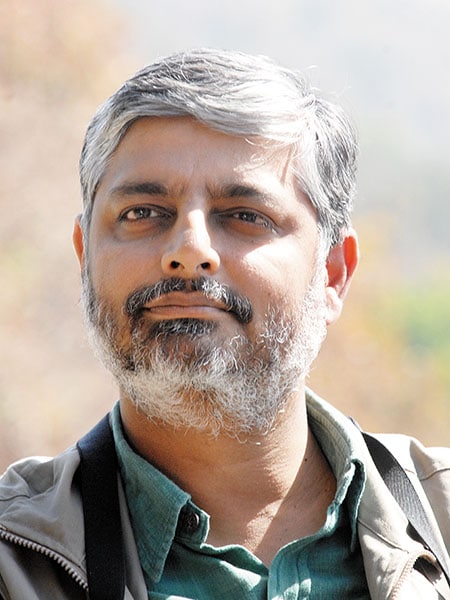

Vivek Menon, founder, trustee, executive director and CEO of Wildlife Trust of India, talks about the threats and hopes facing wild elephants in India

An elephant and a calf at the Thirunelli-Kudrakote corridor at Wayanad, Kerala

An elephant and a calf at the Thirunelli-Kudrakote corridor at Wayanad, Kerala

Image: Wildlife Trust of India

Q. What are the broad areas in which the Wildlife Trust of India functions?

The Wildlife Trust of India (WTI) was started 20 years ago and has grown to become one of the largest conservation organisations in the country. We work with about 50 different projects across India, which involves rescue operations, conducting awareness campaigns, and securing migration corridors. Our association with the Elephant Parade falls under our land securement project for elephant corridors across the country.

Fifteen years ago, we mapped the land and identified 88 such corridors last year we updated this list. At present there are 101 wildlife corridors in India. This is an indication of wildlife habitat getting more and more fragmented, because of which animals are having to move from one habitat to another through corridors.

Q. What are the major reasons for the loss of habitat in India?

Agriculture, industrial activity, human habitation and infrastructure projects are some of the broad reasons for the loss of animal habitat. These factors are not universally applicable, and different regions have one or more of these reasons. For instance, in places like Jharkhand, mining is the biggest reason, while in Kerala and Tamil Nadu it is agriculture and infrastructure projects in north Bengal and Assam the problem is of agriculture and tea gardens.

Q. What has been the WTI’s work with elephants in specific?

The way I describe an elephant is by saying it’s a big, intelligent, social nomad. The elephant is a very large animal, and needs to eat 300 kg of food every day. Therefore, it needs to move from one place to another in search of food. As long as they are given the passage to move, they cause no harm to humans.

Our work has involved launching projects on the ground, and demonstrating ways in which conservation efforts can be made viable. Among many other places, we have worked in the Brahmagiri region of Kerala and Karnataka, and the Wayanad region in Kerala, where we have resettled people away from elephant corridors, in the Garo Hills of Meghalaya, where we worked through the local community, and in Uttarakhand, where we worked with the state government.

In Uttarakhand, for instance, we demonstrated how patrolling a rail track and clearing obstructions in the elephant passage can save the lives of elephants who would otherwise get killed on the tracks. We managed the project between 2001 and 2011, during which not a single elephant was killed by trains before we started the project, 11 elephants had been killed on the tracks. After 2011, we handed over the project to the state’s forest department.

In India, every year, about 500 people are killed by elephants, and about 100 elephants are killed by human activity. In a way you say that the elephants are winning the battle. Resettling people away from animal corridors not just saves elephants, but human beings as well.

Last August, on World Elephant Day [August 12], we launched Gaja Yatra, an awareness campaign on the shrinking of elephant habitats and corridors. This has been done through curating 101 works of art that will travel within their states of origin to raise local consciousness. The campaign will culminate in an event in Delhi on August 12 this year, hopefully with the Prime Minister. Subsequently, the 101 works of art will be exhibited in different places across the country.

At the launch of the campaign at Mumbai’s Siddhivinayak Temple, I was talking about the need to build rail bridges over elephant corridors, and said that normally people pray to lord Ganesh to remove all hurdles from their path, but now lord Ganesh is praying to Suresh Prabhu [then Minister of Railways] to remove hurdles from the paths of elephants.

Vivek Menon, founder, trustee, executive director and CEO of Wildlife Trust of India Q. Are these corridors used by elephants alone?

No, wildlife corridors are used by other animals as well, such as tigers, which are also facing loss of habitat. In Meghalaya, the corridors are used by arboreal animals such as gibbons. So we called it the ‘corridors and canopies’ project.

Q. What are the challenges that conservation efforts face in India?

The biggest challenge is economic growth—the government’s agenda of development at any cost the push for 9 percent growth, while the rest of the world seems to be content with far lower rates. It is important to make the government understand that economic growth and conservation of natural heritage can co-exist.

The second major challenge is our population. One-third of the world’s poor live in India, and causes obvious pressures on land and resources.

The third problem is how elephants are taken for granted. The elephant is not like the tiger, which, because of its national animal status, gets more attention and respect. The elephant is somewhat like the cow: We worship it, but severely ill-treat it at the same time. Although it has been given the status of the National Heritage Animal, this is more of just lip-service.

Q. What is the response from private corporations in India, where funds are concerned?

For the last seven to eight years, I have been on the boards of industry confederations. What I have seen is that companies have knowledge about carbon footprints, and pollution. But they do not have much knowledge of the ecology or of conservation. So, our effort has been to make them more aware of wildlife.

Q. How would you say common people in India respond to conservation efforts?

I have worked in conservation projects in more than 100 countries. India is far ahead in its when compared to other Asian countries. The public support here is unparalleled. The people who actually suffer because of wild animals are themselves sympathetic towards those animals. It is strong political will that is lacking in India.

First Published: Apr 08, 2018, 07:50

Subscribe Now