Tech giants amass a lobbying army for epic Washington battle

Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Google spent a combined $55 million on lobbying last year, doubling their combined spending of $27.4 million in 2016

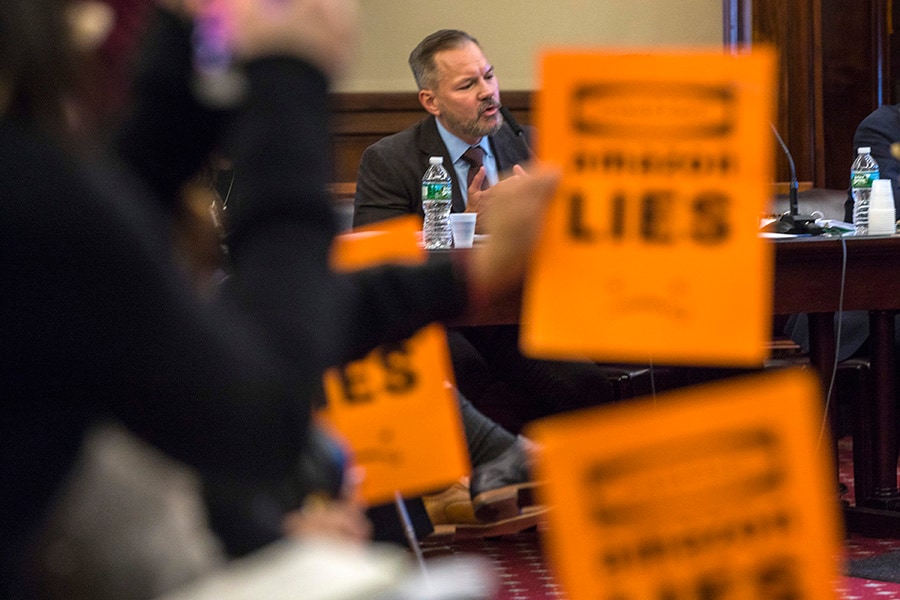

Brian Huseman, Amazon"s vice president of Public policy, during a hearing inside Council Chamber at City Hall in New York, Jan. 30, 2019. Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Google, facing the growing possibility of antitrust action and legislation to rein in their power, are spending freely to gain influence and access.

Brian Huseman, Amazon"s vice president of Public policy, during a hearing inside Council Chamber at City Hall in New York, Jan. 30, 2019. Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Google, facing the growing possibility of antitrust action and legislation to rein in their power, are spending freely to gain influence and access.

Image: Hiroko Masuike/The New York TimesWASHINGTON — Faced with the growing possibility of antitrust actions and legislation to curb their power, four of the biggest technology companies are amassing an army of lobbyists as they prepare for what could be an epic fight over their futures.

Initially slow to develop a presence in Washington, the tech giants — Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Google — have rapidly built themselves into some of the largest players in the influence and access industry as they confront threats from the Trump administration and both parties on Capitol Hill.

The four companies spent a combined $55 million on lobbying last year, doubling their combined spending of $27.4 million in 2016, and some are spending at a higher rate so far this year, according to the Center for Responsive Politics, which tracks lobbying and political contributions. That puts them on a par with long-established lobbying powerhouses like the defense, automobile and banking industries.

As they have tracked increasing public and political discontent with their size, power, handling of user data and role in elections, the four companies have intensified their efforts to lure lobbyists with strong connections to the White House, the regulatory agencies, and Republicans and Democrats in Congress.

Of the 238 people registered to lobby for the four companies in the first three months of this year — both in-house employees and those on contract from lobbying and law firms — about 75% formerly served in the government or on political campaigns, according to an analysis of lobbying and employment records. Many worked in offices or for officials who could have a hand in deciding the course of the new governmental scrutiny.

The influence campaigns encompass a broad range of activities, including calls on members of Congress, advertising, funding of think-tank research and efforts to get the attention of President Donald Trump, whose on-again, off-again streak of economic populism is of particular concern to the big companies.

Last month, the industry lobbying group, the Internet Association, which represents Amazon, Facebook and Google, awarded its Internet Freedom Award to Ivanka Trump, the president’s daughter and White House senior adviser.

“They are no longer upstarts dipping a toe in lobbying,” said Sheila Krumholz, the executive director of the Center for Responsive Politics. “They have both feet in.”

Facebook and Google are dogged by concerns over their handling of consumer data, harmful content and misinformation. Amazon’s rapid expansion has been met with unease over labor conditions and the company’s effect on small businesses. Apple’s control over its app store makes it hard for new apps to get discovered, some rivals say.

Earlier this week, the threat of government action became more real, driving down their stock prices. The House Judiciary Committee announced a broad antitrust investigation into big tech. And the two top federal antitrust agencies agreed to divide oversight over Apple, Amazon, Facebook and Google as they explore whether the companies have abused their market power to harm competition and consumers.

“Unwarranted, concentrated economic power in the hands of a few is dangerous to democracy — especially when digital platforms control content,” Speaker Nancy Pelosi tweeted after the Judiciary Committee announced its investigation. “The era of self-regulation is over.”

The industry’s troubles mean big paydays for the lawyers, political operatives and public relations experts hired to ward off regulations, investigations and lawsuits that could curtail the companies’ huge profits. The companies all had earlier ties to Democrats but have also worked to develop closer relationships with Republicans.

Facebook is paying two lobbyists who worked for Pelosi, including her former chief of staff, Catlin O’Neill, who now serves as a director of U.S. public policy for the social media company.

Pelosi received nearly $43,000 in total donations for her 2018 re-election campaign from employees and political action committees of Facebook, Amazon and Alphabet, Google’s corporate parent — each of which ranked among her top half-dozen sources of campaign cash. She had been a champion of tech companies, which have a robust presence in her district in California.

But her support for the industry appeared more tenuous last month, when she said Facebook’s refusal to take down a doctored video of her that made her appear drunk demonstrated how the social network contributed to misinformation and enabled Russian interference in the 2016 election.

Google is paying two contract lobbyists who worked as lawyers on the Republican staff of the House Judiciary Committee. One of the lawyers, Sean McLaughlin, also served as a deputy assistant attorney general under President George W. Bush.

“Having conducted congressional investigations from the inside, Sean is able to counsel clients on how to respond to them from the outside,” reads McLaughlin’s biography on the website of his firm, Hunton Andrews Kurth LLP, which was paid $50,000 by Google to lobby Congress during the first three months of the year, according to lobbying records.

The Washington office of Amazon, whose chief executive, Jeff Bezos, has drawn regular criticism from Trump, is led by a former Federal Trade Commission official, Brian Huseman. And its roster of outside lobbyists includes three Democratic former members of Congress — Norm Dicks of Washington, Vic Fazio of California and Kendrick Meek of Florida — as well as two former Justice Department lawyers.

One of them, Seth Bloom, was a trial lawyer in the department’s antitrust division in the late 1990s before going on to work on antitrust issues for the Senate Judiciary Committee’s Democratic staff. He went on to lobby for Amazon, including in connection with its purchase in 2017 of grocery chain Whole Foods, which required a review of competition concerns by the Federal Trade Commission. Amazon paid $30,000 to Bloom’s firm to lobby Congress on issues “related to competition in technology industries” during the first three months of the year.

In that span, Amazon also paid $70,000 to the lobbying firm of a top Trump fundraiser, Brian Ballard, to lobby Congress and the administration. Top-tier lobbyists in Washington can make millions of dollars a year.

One of the lobbyists on the account for Ballard’s firm, Daniel F. McFaul, worked on Trump’s presidential transition team and then briefly as chief of staff for Rep. Matt Gaetz, R-Fla. Gaetz is a member of a House Judiciary subcommittee that is planning a set of hearings, testimony from executives of top companies and subpoenas for internal corporate documents.

The internet giants have learned from the hard lessons of Microsoft, which was caught flat-footed with a sparse lobbying presence in the 1990s when federal antitrust officials called for a breakup of the software giant. Google has especially been forced to deal with regulatory issues, both in Europe, where it has been hit with three multibillion-dollar penalties, and in the United States, where it escaped an Obama administration-era Federal Trade Commission investigation without any action being taken.

The companies have separately argued that they have not violated antitrust laws. Google and Facebook say that their services are free and do not harm competitors and that consumers can turn to alternative search and social networking apps. Amazon has said it has a large share of online commerce but only a small fraction of the overall retail market. And Apple argues that the majority of apps in its store are free and that the company rejects only apps that violate its policies on hate speech and pornography, for instance, or try to take too much data from users.

“We have seen these tech companies escape accountability for years,” said Lisa Gilbert, the vice president of legislative affairs for the government watchdog group Public Citizen. The group, which has called for more user data protections and for breaking up Facebook, published a study last month showing that in the last two decades, 59% of top Federal Trade Commission officials who left the agency entered financial relationships with technology interests regulated by it.

The head of the Justice Department’s antitrust division, Makan Delrahim, was paid as a contract lobbyist by Google in 2007 to win approval for its acquisition of DoubleClick, which had drawn antitrust concerns. He is now facing pressure to recuse himself if the Justice Department pursues an investigation of the company.

Federal employees are barred from working on specific issues that affect their former private sector employers or interests, and generally face “cooling off” periods of one to two years after leaving government, during which they cannot lobby their former colleagues. But there are all manner of loopholes.

Gilbert’s group has called for stricter conflict-of-interest provisions. She said that “in this moment of enhanced scrutiny, the tech companies are going to be looking for those who have the Rolodexes that matter to try to stop regulation and legislation of the type that’s required to protect consumers.”

First Published: Jun 06, 2019, 11:14

Subscribe Now