Toppr: From the old school

How a battery of feet-on-street counsellors that doubles up as a sales army is helping Toppr score in revenue and reach. Will the offline gambit pay off for the edutech startup?

“Online education is not ecommerce.” Zishaan Hayath, co-founder, Toppr

Image: Ritesh Uttamchandani for Forbes India

It was in early 2016 when Rishabh started losing interest in studies. Or so it seemed. “It all started with maths,” recalls Reeta Tandi, Rishabh’s mother, who works in a government medical department in Raipur, the capital city of Chhattisgarh, which boasts a campus of India’s premier business school, Indian Institute of Management. “He dreaded maths,” rues Tandi, who is back from work at 7.30 pm. Till class IV, she lets on, Rishabh was a bright student. “In fact he came third in the class.” A visibly-hassled Tandi shares her fond memories with Aditya Shukla, who has come home for a counselling session with Rishabh, a student of class VII, on a Friday, around 8.30 pm.

A commerce graduate in his mid-20s, Shukla patiently hears out Tandi’s tale of what went wrong with her son who studies at one of the top three private schools in Raipur. “How much did he score in the half-yearly exams?” he asks. “20 in maths, 40 in English and 25 in science,” laments Tandi, staring at her jittery son who is sitting on the edge of a sofa. The 12-year-old, feverishly biting his nails, avoids eye contact with his agitated mother who put him in a coaching institute last November. “Stop playing games on the mobile,” she howls. “He knows nothing and doesn’t ask anything in the class,” Tandi says in exasperation. “He is fast becoming a failure.”Shukla now intervenes. “He has not failed, ma’am. He is not getting answers to his questions,” reckons Shukla, who spends an hour with him and explains the ‘concept of triangles’ on his laptop.

Around 9.30 pm, Shukla comes up with his diagnosis: Overcrowded classes—both at school and the coaching centre—no personalised attention, hesitation in asking questions for the fear of being ridiculed by peers and snubbed by teachers, and a resultant loss in self-confidence. “The poor kid is trapped in this vicious cycle,” he says. Rishabh nods, as he packs his school bag for the next day. “It’s too heavy,” he grumbles. Meanwhile, his mother evinces interest in buying a one-year pack for an online module of ‘learn, test and doubt’ for ₹21,000. The deal gets closed at 10 pm.

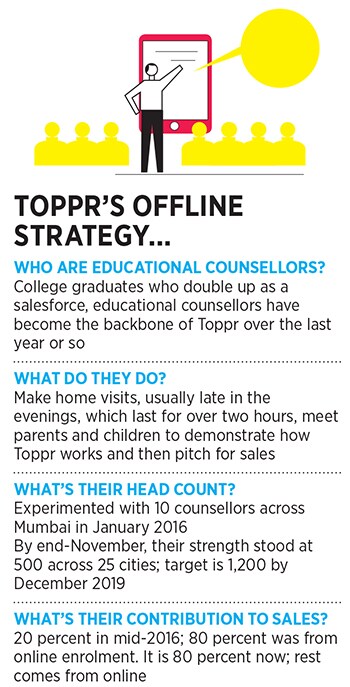

Shukla, for his part, adds another feather to his cap of being the top performer in the state for Toppr, an online learning platform offering school courses from classes VI to XII and test preparation for competitive examinations such as IIT and JEE. The counsellor, who also doubles up as a salesman pitching online learning packages to anxious parents, is one of the edutech startup’s 500 counsellors across 25 cities in India.

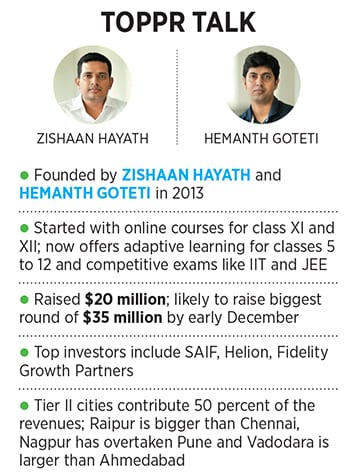

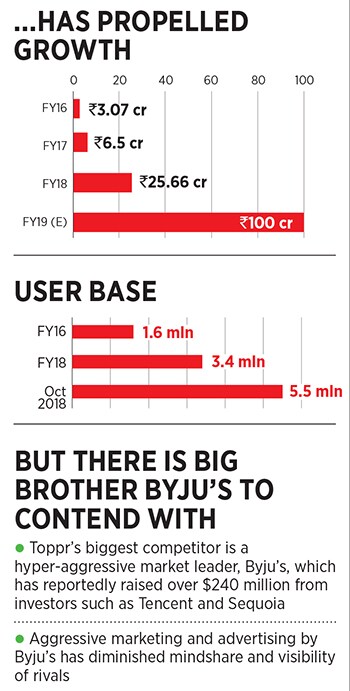

Toppr doesn’t follow the conventional style of classroom teaching. It relies on interactive video lectures focusing on clarity of concepts though apps, personalised learning at a pace fixed by a student, round-the-clock resolution of queries and endless practice question sets. Yet, ironically, it is the old school of offline marketing by its battery of counsellors that is working wonders for the online startup. From ₹6.5 crore in the March ended fiscal 2017, Toppr’s revenues surged almost four-fold to ₹25.66 crore a year later. Founded by Zishaan Hayath and Hemanth Goteti in 2013, Toppr says it is now cruising at a revenue run rate of ₹100 crore in the current fiscal. Losses, however, were a hefty ₹59 crore in fiscal 2018. Toppr’s education counsellor Aditya Shukla with the Tiwari family in Raipur, Chhattisgarh Experiment That Clicked

Toppr’s education counsellor Aditya Shukla with the Tiwari family in Raipur, Chhattisgarh Experiment That Clicked

What started as an experiment of having counsellors in early 2016 has now become the backbone of Toppr, which has raised $20 million in funding so far from marquee investors like SAIF, Helion and Fidelity Growth Partners. The edutech venture, which is likely to raise its biggest round of $35 million by early December, has seen its user base swell from 1.6 million in fiscal 2016 to 5.5 million in two years.

With 1.6 million users, revenues of ₹3.07 crore and a loss of ₹23 crore in fiscal 2016, there was something amiss in the business strategy. Hayath decided to shut down the B2B vertical in January 2016. “This was not a right channel to sell a consumer product,” he recounts. The B2B team, however, pleaded for three months to try to reach out to parents directly across Mumbai. Though not convinced, Hayath gave in to the request.

The pilot turned out to be a hit. The team started getting more business. Hayath opted to continue with the plan, with some modifications. The size of the team was increased to 20 and more money was pumped into the operations. The results, again, were startling. By June 2016, 20 percent of business was coming from this channel. The team, Hayath stresses, was not aggressively pushing the product but understanding the requirement of students and then offering a solution suited to them. “Need identification, customised offering and trust building added a new dimension to the business,” he reckons.

The performance of the offline team had another surprise element. The order value doubled. It became twice the size of what the sales team was managing to get by doing business over phone. Reason: Reaching out to parents at home added to the credibility of Toppr and beefed up the trust factor. “Instead of buying a ₹15,000 package, parents were buying the ₹30,000 one,” Hayath contends. “It was an eye-opener.” He adds that by the end of the 2018 fiscal, 80 percent of revenues were coming from this channel and the rest from tele sales.

There was another area in which the offline team proved to be a blessing: Collection of money. From suggesting a mix of payment options, the counsellors aided the parents in going deeper into their pocket.

Offline Added Credibility

Hayath expanded his team to 500 counsellors by the end of this October and reached out across 25 cities. The move seems to have paid off as revenues have grown four-fold over last year, and tier II cities now make for over 50 percent of revenue for Toppr. By the end of October, over 95 percent of the revenue was generated by the offline team.  “Raipur is bigger than Chennai for Toppr. Nagpur has overtaken Pune and Vadodara is larger than Ahmedabad,” claims Hayath. “Dearth of quality teachers and crammed classrooms explain what’s wrong with our educational system,” he points out, explaining how coaching centres, which were once billed as solution to what was missing in classroom teaching, have become a larger problem. “There’s no personalised learning. One size never fits all.”

“Raipur is bigger than Chennai for Toppr. Nagpur has overtaken Pune and Vadodara is larger than Ahmedabad,” claims Hayath. “Dearth of quality teachers and crammed classrooms explain what’s wrong with our educational system,” he points out, explaining how coaching centres, which were once billed as solution to what was missing in classroom teaching, have become a larger problem. “There’s no personalised learning. One size never fits all.”

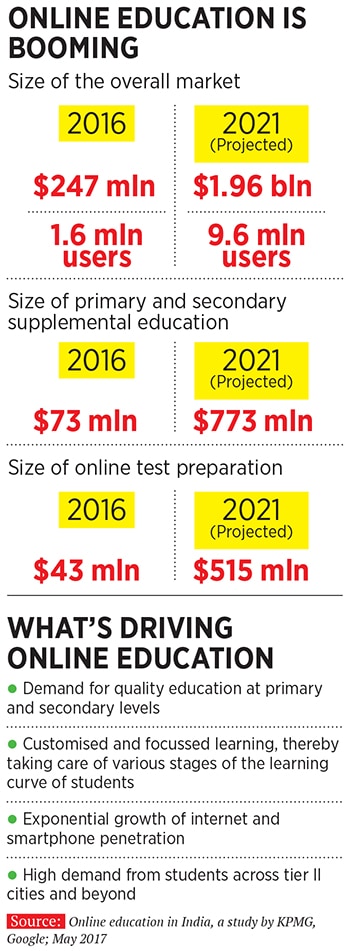

A report by the National Sample Survey Organisation in April 2016 attested to the growing culture of coaching or private tuitions. An estimated 7.1 crore students, the report said, were taking coaching classes or tuitions. Around 11-12 percent of total expenditure incurred by families is on coaching and tuitions. On the other hand, if one looks at the projections for the growth of online education in India, one gets to see how a transition to the app-based learning module is taking place in the country.

The size of the primary and secondary online supplemental education pie, which stood at $73 million in 2016, is projected to touch $773 million by 2021, according to a study conducted by KPMG-Google last year. With over 280 million students estimated to be enrolled in schools by 2021, online primary and secondary supplemental education will have a 39 percent market share by 2021. Online test preparation will also see a corresponding boom: From $43 million in 2016 to $515 million in 2021. Pegged to grow at a compound annual rate of 64 percent over five years, online test preparation will be the fastest growing category of online education. “As a supplementary educational tool, we are not fighting against the schools but inefficient coaching centres,” says Hayath. Mumbai, he lets on, is the biggest market for Toppr.

Just a few kilometres away from the corporate headquarters of Toppr in Hiranandani Gardens in Powai, Mumbai, Orbit Coaching Centre is buzzing with energy. Some 70 students of class VIII are packed inside a small classroom. There is little legroom or elbow space. Nobody is complaining. “My parent won’t agree to app-based learning,” says Rohan Patil, 14, who is enrolled in a public school. Like many parents, Rohan’s too would prefer a human face. He highlights another concern. “Mobile learning would mean more screen time for me. This they would not allow at all,” he grins.

It’s perhaps to deal with such mindsets that Byju’s, the biggest edutech player in India, has been aggressively advertising on television. Endorsed by actor Shah Rukh Khan, the commercial tries to reach out to parents, exhorting them to buy Byju’s for their kids. The task, though, is not easy. An advertising blitzkrieg, reckons Ashita Aggarwal, marketing professor at SP Jain Institute of Management and Research, might have made Byju’s a generic name for app-based learning, but parents still prefer a classroom environment. “Classroom still remains the first choice,” she says.Experts point out the flip side of e-learning: No direct connect. In a normal environment, a teacher assesses the students’ aptitude and capability, and plans lessons accordingly, says Anindya Mallick, partner at Deloitte India. Mallick, though, is quick to point out the positives of online learning. With the content being well researched and graphical, concepts are delivered with much better clarity. “Such form of learning, though, will not replace classroom teaching,” he adds.

Back in Raipur, homemaker Anju Tiwari is a staunch believer in the power of the online medium. Her daughter Anamika, a class IX student, has been struggling with physics and chemistry. “Coaching centres have become a money-minting business,” she says, adding that her decision to opt for Toppr has to do with the feedback of most of her friends who felt duped by sending their children for private tuition.

A small army of on-ground counsellors may have managed to propel Toppr on a high-growth trajectory, but the going won’t be easy. The biggest challenge is Byju’s, which has raised over $240 million from investors such as Tencent and Sequoia so far, and has also embraced a feet-on-street approach. In fact, at Shyma Plaza mall in Pandri, the commercial hub of Raipur, while Toppr is on the second floor, Byju’s is on the third.

Sid Talwar, partner at venture capital firm Lightbox, reckons that while there is tremendous opportunity at the intersection of education and technology, online businesses trying to take advantage of it face a myriad of problems.

First, it takes patience to build an education product to fit a market need. “Successful education products aren’t built purely around information dissemination,” he reckons. The successful ones, Talwar explains, attempt to figure out if students are actually mastering the knowledge that they’re setting out to learn. “And that kind of a product isn’t possible to build overnight.”

Another challenge for Toppr would be to sustain its personalised touch with every student as it scales up, says Alok Goel, managing director at SAIF. Google, he explains, is for billions as well as has a personalised offering for a single individual. “Can Toppr manage to do that?” he asks.

Hayath, for his part, is content with word-of-mouth growth. “Online education is not ecommerce,” he says. Toppr has the highest daily engagement rate of 110 minutes with a user, he claims. The pace of growth is not determined by hours advertised on television or money burnt on having a celebrity endorser, he adds. “Slow and steady always wins the race.”

First Published: Nov 20, 2018, 12:50

Subscribe Now