Can quick commerce startups ride out the downturn?

As cheap capital becomes unavailable, can the cash-guzzling startups that put groceries on people's doorsteps in under 20-minutes survive?

In its earnings call last week, Zomato said, in not so many words, that it would scale back its instant delivery aspirations. Just a year ago, quick commerce, which aims to put groceries on people’s doorsteps in less than 20 minutes, was one of the hottest areas of VC (venture capital) investment. It attracted $12-13 billion in funding, globally, in just one year.

In India, Zepto, a year-old-startup founded by two 19-year-old Stanford dropouts, raised a total of $360 million (roughly Rs2,754 crore), catapulting its valuation to $900 million in record time. Dunzo Daily, another quick commerce player, received a $200 million (Rs1,488 crore) investment from Reliance Retail in return for a 25.8 percent stake in January. Around the same time, Swiggy, the food delivery behemoth, also raised $700 million (Rs5,225 crore) in fresh funding led by US-based investment firm Invesco to bolster Instamart, its instant grocery delivery service.

Even Zomato snapped up a 9.3 percent stake in Blinkit (formerly Grofers), a 10-minute grocery delivery service, for $100 million (around Rs745 crore) in convertible notes in March. Although this is a financial investment with no bearing on Zomato’s operations, speculation was rife that the food delivery giant would take over Blinkit and integrate its operations into its own. But Zomato has remained non-committal about it.

“For now, we are being aggressive about conserving cash," said Deepinder Goyal, founder and CEO of Zomato, in a shareholder’s letter released just prior to the earnings call. The company, he said, would not make any fresh investments other than the $400 million it had previously earmarked for the quick commerce space to be spent over CY22 and CY23.

But he also said that Zomato was bullish about the long-term prospects on quick commerce. “We think there is a market [for quick commerce] and this model is more efficient than the kirana model." Zomato, which had also been experimenting with 10-minute food deliveries around Gurugram, will continue those pilots without further scaling up.

“The management has reiterated they remain bullish about the quick commerce space and see definite synergies," says Pranav Kshatriya, equity analyst at Edelweiss. “We believe that a foray into quick commerce can be a concern, so the management’s decision to have an outer limit of $400 million investment implies that capital allocation is prudent." Further, he says he’s “comfortable" with the management’s non-committal stance on the Blinkit takeover. “Any deviation that defers profitability would be a key risk," he points out.

First, quick commerce took hold at the height of the coronavirus pandemic when people were locked down in their homes and needed groceries delivered to them. Globally, startups took advantage and forayed into the space. In India, similarly, Swiggy, Blinkit, Zepto and Dunzo Daily pushed into rapid delivery services, ferrying groceries from small urban warehouses or “dark stores" to customers’ doorsteps. But in a post-pandemic world, the same urgent need for delivery isn’t there. “I would argue that the need for a 10-minute delivery service, even then, was questionable. And the worth of such a service—in terms of risking riders’ lives to deliver the goods on time—was also questionable," says Padmaja Ruparel, president of the Indian Angel Network.

Second, the macro environment has changed. Last year, capital was easy to raise and valuations were sky-high, pushing many to make “opportunistic" bets in the quick commerce space, says one investor on condition of anonymity. “Let’s just say most didn’t have the best intentions when they got into the space. They were in it to make a fast buck."

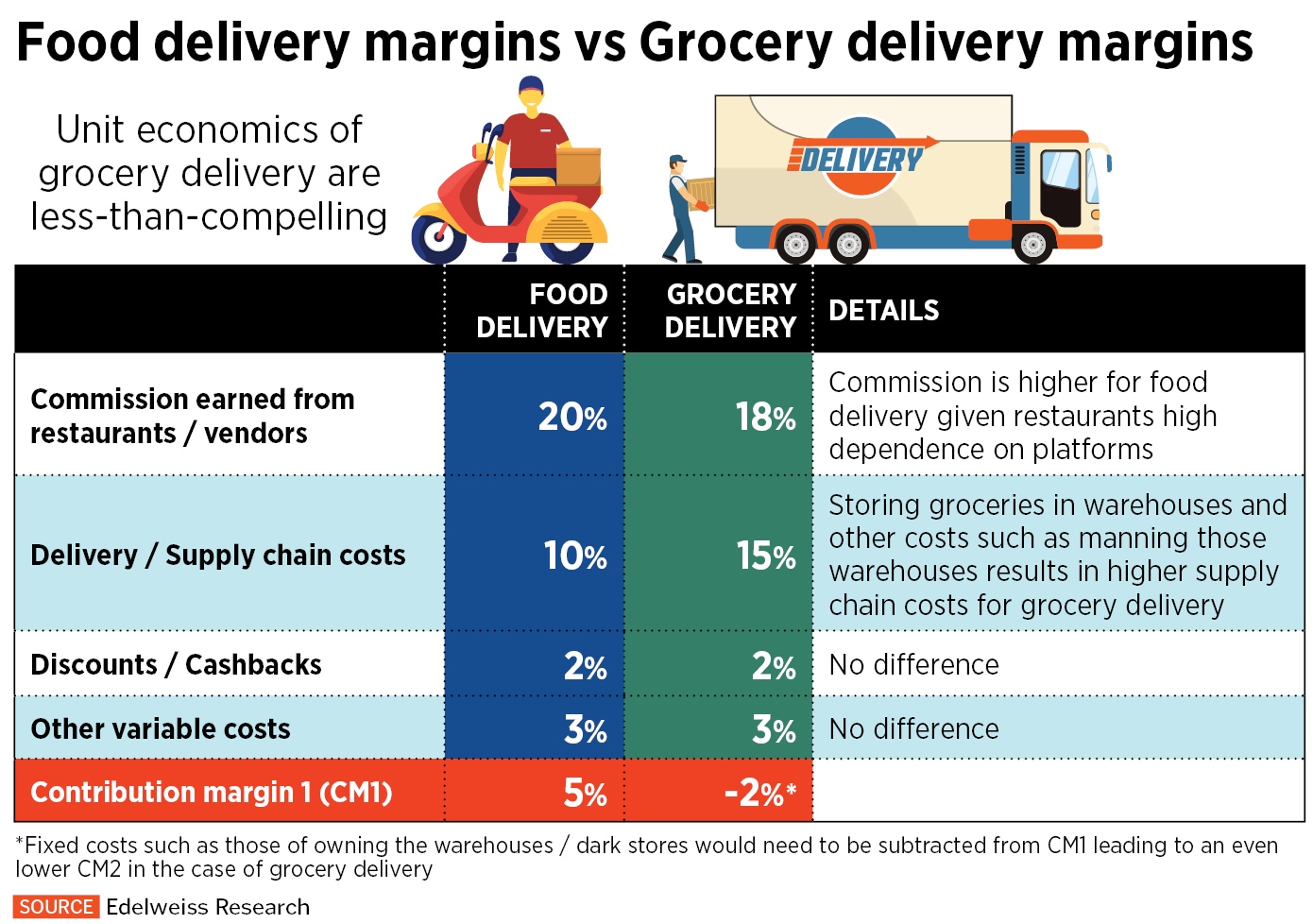

Rolling out a quick commerce—think owning and operating dark stores—requires an upfront investment in property and logistics. It’s capital intensive unlike traditional food delivery. And the unit economics are far from compelling. According to Edelweiss’ Kshatriya, grocery delivery yields a negative contribution margin compared to food delivery (roughly 5 percent) after adjusting for variable costs like supply chain costs, delivery charges and discounts. If one accounts for the fixed costs of dark stores, the margins are even redder.

Now that cheap capital is scarce, and investors turn away from cash-guzzling businesses, will we see other quick commerce players scaling back too like Zomato? Or perhaps even folding up?

“Yes, we will most likely see some churn," says Ruparel. “This is a high-capex game and when these companies started, the mood was not what it is today. Investors are looking more scrupulously at whether a business is stable and sustainable in the long run."

In many ways, the quick commerce space today is reminiscent of the food delivery space in 2015-16 when multiple players jostled for market share, prioritising growth over profit. Eventually most folded up or got snapped up and the market settled to a duopoly with Swiggy and Zomato.

Globally, quick commerce companies are faltering. In the US, Softbank-backed GoPuff was reportedly eyeing an IPO at a valuation of $40 billion in January. By March, it shelved its IPO plans and investors have been struggling to sell their stakes for as low as $15 billion. DoorDash, another US-based food delivery platform that ventured into ultra-fast grocery deliveries in December 2021, has seen its stock price tumble from about $245 at the time to roughly $70 in early June—a 70 percent fall. Similarly, Germany’s Delivery Hero, listed on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange, saw its share price crater from 128 euros in November 2021 to around 36 euros at the time of writing this article. In Europe, there were 30 companies competing in the super-fast, hyper-convenience space in September 2021, according to Euromonitor. They’ve since been frantically consolidating: GoPuff bought Britain’s Fancy and Dija, Turkish startup Getir acquired London-based Weezy and Barcelona’s Blok, and Berlin’s Gorillas snapped up France’s Frichti. In Australia, Send, an instant grocery provider, collapsed in June because money ran out.

“We are seeing investor exuberance for quick commerce waning," says an analyst, who isn’t authorised to speak to the media. According to him, Swiggy’s Instamart leads the quick commerce pack in India and will likely continue to do so because of the synergies with its core food business and existing delivery fleet. “But we will see a shakeout among the Zeptos, Dunzos and Blinkits," he says.

However, according to RedSeer, quick commerce is here to stay. In fact, the consultancy expects the market to grow 15x from about $300 million currently to $5.5 billion by 2025. “In grocery purchases, we’ve seen a strong habit formation among customers [because of the pandemic]. They are actually moving their kirana purchases and scheduled online deliveries to quick commerce platforms because of the convenience involved," says Rohan Agarwal, partner at RedSeer.

According to him, quick commerce has seen a significant adoption in markets like Bengaluru, Chennai and New Delhi. Average order values (AOV) are about Rs350 versus Rs1,050 for scheduled delivery players like Amazon Fresh. Interestingly, the latter has stayed away from quick commerce, instead promising deliveries within a two-hour window in cities like Bengaluru and Delhi.

In the last six to eight months, quick commerce’s share in the total online grocery pie in India has grown to a cool 20 percent, from single digits earlier, says Agarwal. The figure is set to grow in the long term, he says, but in the short term, players will be “conservative on the spending side". Dark store expansions, for example, will slow down, discounts will get rationalised and delivery fees might be charged to customers. On the other hand, companies will look to improve their margins by moving into categories like fresh fruit and vegetables that have margins of 20 to 25 percent as opposed to staple groceries that operate on margins as thin as 7 to 8 percent.

Meanwhile, Zomato may have pulled back its quick commerce play for the time being, but others are setting up. Tata Group-owned BigBasket, India’s largest online grocer, announced the launch of BBnow to offer 10 to 20-minute deliveries of over 3,000 products. “They have the firepower to sustain the business and ride out the downturn," says Ruparel. Warpli, a Gurugram-based startup, promises to deliver fashion, beauty, electronics and home furnishings in less than 30 minutes. It was launched earlier this year by Saurabh Kumar, who had previously co-founded Blinkit.

First Published: Jun 02, 2022, 12:44

Subscribe Now