Though it’s lunch time, the office wears a subdued look as employees have been working from home. A huge yellow hoarding announcing ‘Grofers is now Blinkit’ does its best to brighten up the mood as Goyal sets the tone for an animated conversation around quick commerce. “Thirty minutes is neither here nor there," he says, alluding to the delivery time of some of Grofers’ rivals in the segment. “Swiggy is still not doing instant commerce," he reckons. Blinkit, in which Zomato is a minority investor, delivers in 10 minutes. “Only 10 minutes make sense," he says.

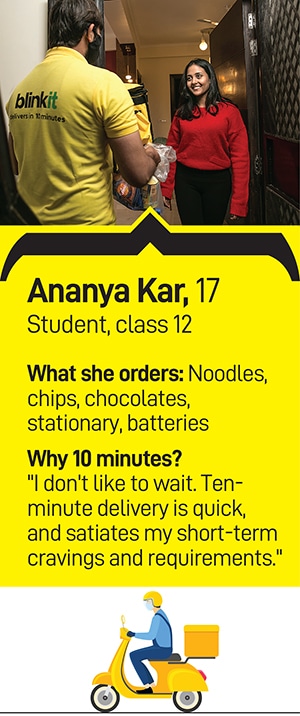

Around 18 minutes and 7.5 km away, Ananya Kar agrees with the 38-year-old entrepreneur who had a blockbuster IPO last July. “Delivery has to be really quick to make sense," reckons the high school student. From cup noodles to chips, chocolates, stationery and batteries, the 17-year-old refills her ‘craving’ list every night, and even afternoons, by placing orders on Blinkit. Tell her that there is a convenience store just 500 metres from her residence, and Kar grins: “Why go when you can get it in 10 minutes?"

Meanwhile, in Berlin, Germany, Shubhankar Bhattacharya decodes why venture capitalists (VC) loaded online grocery in India with the most funds last year. In 2021, the segment mopped up $1.7 billion to top the most-funded segments’ chart social platforms like Josh, ShareChat, foodtech and edtech followed, in that order. One undeniable-but-under-appreciated truth that drives consumer adoption—and VC interest—is that consumers love being lazy and will adopt solutions that enable them to stay lazy, explains Bhattacharya, general partner at Foundamental, an early-stage VC firm.

The pandemic provided the perfect reason, or excuse, for being lazy at home. “The rise of quick commerce has to be seen in this context," avers Bhattacharya. There has been a tectonic shift in the way people consume goods over the last two years. What if the future of all grocery, essential and retail purchases lies in a more ‘on-demand’ and ‘streamed’ version, the investor asks. “The latest avatar of that future is quick commerce startups and their 10-minute play."

Back in Gurugram, Goyal explains his quick play. Zomato, he underscores, is at the confluence of food and hyperlocal ecommerce. What powers the business is the last-mile hyperlocal delivery fleet, of over 3 lakh delivery partners on a monthly active basis. “This is a strong moat and it sets us up well for building one of the most meaningful hyperlocal ecommerce companies in India in the long term," he says. The company, he adds, is bullish about the various use cases it can plug its delivery fleet into. “We can be the primary contenders for building large businesses in hyperlocal ecommerce in India."

![]()

Goyal’s game plan is simple: To quickly invest rather than build in-house. Over the last few months, he has aggressively backed a bunch of hyperlocal ecommerce companies, including ecommerce enablers, to add more layers to the existing core of food delivery. Consider: Zomato has bought a 16.1 percent stake in Magicpin, a hyperlocal commerce startup 7.89 percent in ecommerce logistics firm Shiprocket 6.4 percent in online fitness firm Curefit, and a $100 million infusion for a 9.16 percent stake in Grofers, which was rebranded Blinkit in December.

Overall, Zomato reportedly committed $275 million across these four companies within a span of four months. “We want to take an investment route for these businesses rather than build them in-house," says Goyal. There is more money lined up: Another $1 billion over the next one or two years, and a large chunk of it will likely go into quick commerce.

![]()

The biggest and boldest bet seems to be Blinkit. The quick commerce delivery player has been running at a scorching pace since it started its 10-minute pilot in August. Blinkit has opened over 330 operational dark stores across eight cities and plans to hit 500 by the end of January 2022. The company claims to be clocking a run rate of over 4 million monthly orders and, in December, it claimed to be opening one store every four hours.

Hyperlocal commerce, Goyal reckons, is very close to what Zomato is as a business. “It’s just that a different product is being ordered, but most of the mechanics are the same," he argues. Food and grocery, he lets on, are different things but the principles are the same. High online grocery penetration has remained elusive in India for the past 7-8 years. The country might finally be at an inflection point with widespread adoption in the 10-minute delivery format, he adds.

If one goes by the products delivered by Blinkit on December 31, the user base seems to be wide, and the items ordered diverse: From potato chips, cold drinks, ice packs, instant noodles and namkeens to matchboxes, hookah flavours, Covid-testing kits, lemons and condoms. “There is a product-market fit," says Goyal, adding that people are realising the need for instant and are moving away from planning their needs a day in advance.

![]()

Blinkit not only fits into Zomato’s larger scheme of things but also gives it a presence in the hyperlocal space. Rival Swiggy is aggressively expanding its own presence here, with Instamart, and is reportedly in talks to buy a stake in bike taxi player Rapido. Dunzo has built a strong consumer base over the last few years and has bagged backing from Reliance Retail, which picked up a 25.8 percent stake by leading a $240 million round Walmart-backed Flipkart is rapidly scaling its hyperlocal play and Amazon is getting bullish on its grocery business.

The scramble to get into quick commerce is not hard to fathom. The market in India is estimated to leapfrog to $5 billion in 2025 from $0.4 billion last year. And the growth is coming on the back of a booming online consumables market which is set to become $30 billion in 2025 from just $3.8 billion in 2020. Half of this growth will come from metro and Tier I cities, according to a report by consulting firm Redseer. “There is a lot of synergy between food delivery and quick commerce," says Rohan Agarwal, director at Redseer.

Prod Goyal to elaborate on the potential synergies he envisioned between Zomato and Blinkit before making the investment, and his response is guarded. “I can only say what is out there in the public domain. Now we are a public company," he smiles. “We are newly there. So I would prefer to err on the side of not saying stuff that I have not said earlier."

![]()

The newly-listed company, though, is quick to learn from its solo grocery experiments. Twice since the onset of pandemic in March 2020, Zomato flirted with grocery delivery. The second time, it eventually abandoned a pilot run of 45-minute delivery in a few markets of Delhi-NCR in July last year. The first time was during the lockdown in mid-2020. In an email reportedly sent to its employees last September when it pulled the plug on its grocery venture, the food delivery major shared the reasons for exiting. The grocery service, the email outlined, had moderate success, faced a few challenges, including frequent changes in inventory and gaps in order fulfilment, leading to a poor customer experience.

Zomato CFO Akshant Goyal outlines three parts of the long-term play. First is ‘brutal prioritisation’. This means divesting or shutting down businesses that aren’t likely to drive exponential value for shareholders in the long term. Second is invest in core food businesses and the ecosystem around them to make it a robust long-term value driver. And, lastly, build the hyperlocal ecommerce ecosystem by leveraging Zomato’s key strengths to invest and partner with other companies to tap into growth opportunities beyond food.

![]()

The core of Zomato’s investment strategy is to help the new companies scale. As they do, the CFO explains, the parent will provide capital and consolidate its holdings. This might lead to a potential merger at some point if the founders of these companies want to or, otherwise, would result in learnings and financial returns for Zomato.

The strategy, in a large part, is inspired by Chinese ecommerce. Alibaba and Tencent invested in the ecosystem, created multiple merger and acquisition (M&A) options, and in the eventuality of any M&A not panning out, realised windfall financial gains from investments made in market leaders across different categories. The Zomato CFO underlines that the company is only investing behind founders with potential to be market leaders. “All our investments are a mix of math and chemistry," he contends.

In Gurugram, Blinkit founder Albinder Dhindsa explains how and why the chemistry and math of Grofers didn’t work out. For a company, which ironically had its origin in hyperlocal delivery, Blinkit is a sort of homecoming. “Back in 2015, we were a frontrunner in quick commerce," recounts Dhindsa, who headed international operations of Zomato before co-founding Grofers in late 2013.

![]()

Grofers’ initial pace of growth, both in operations and in mopping up funds, was staggering. In November 2015, it raised $120 million led by SoftBank. The Series C round of funding, which also included existing backers DST’s Apoletto Managers, Tiger Global and Sequoia Capital, was the third that year.

It had earlier raised $10 million and $35 million, bloating its funding kitty to just under $166 million. What happened over the next two years, apart from a funding freeze in 2016 and 2017, was a series of pivots. From a marketplace model, Grofers moved to inventory-led model, it dumped the 90-minute delivery play and focussed on private labels to survive the bruising battle against leader BigBasket. Battling a funding crunch, in February 2018, the online grocery player raised money from existing investors at an approximately 40 percent lower valuation than its previous round in 2015. Survival was at stake.

A year later, in May 2019, it managed to raise $220 million from SoftBank Vision Fund and other investors. The funding round was not just the biggest in India’s online grocery delivery, but it also came a few weeks after Alibaba-backed BigBasket raised $150 million. While both companies kept aggressively building war chests, losses piled up, and unit economics went for a toss. Grofers reportedly closed FY19 at a loss of ₹448 crore and revenue of ₹71.04 crore. BigBasket had losses of ₹348.27 crore on revenue of ₹2,380.95 crore.

![]() Meanwhile, Dhindsa’s struggle to raise funds continued. For investors, hyperlocal grocery had become a two-player race, and there was no meaningful growth. “For them, the question was why to put money here versus other segments which were more promising," he recounts. Dhindsa doesn’t blame the investors. “They too have their skin in the game and didn’t have any incentive to leave their portfolio company to die." At different points in time, he stresses, Grofers had different investors. “At some point, the same set of people backed out. Now, you can’t take it personally."

Meanwhile, Dhindsa’s struggle to raise funds continued. For investors, hyperlocal grocery had become a two-player race, and there was no meaningful growth. “For them, the question was why to put money here versus other segments which were more promising," he recounts. Dhindsa doesn’t blame the investors. “They too have their skin in the game and didn’t have any incentive to leave their portfolio company to die." At different points in time, he stresses, Grofers had different investors. “At some point, the same set of people backed out. Now, you can’t take it personally."

Funding or no funding, what didn’t change for Dhindsa was his eternal quest for a business that can lead to outrageous outcomes. The founder spotted a glimmer of hope last year, when he started tasting success in 10-minute delivery. “We saw a hockey-stick like growth," he says, adding that a few dark stores were opened in Delhi-NCR to pilot the venture. The plan to go for a SPAC (special purpose acquisition company) listing in the US was shelved just two weeks before filing the papers.

Though the listing would have provided access to capital, it would not have let Dhindsa continue with his quick commerce experiment. “If you are going public, you can’t be so dramatic in your plans," he says. Grofers needed another pivot. “There was a massive opportunity in having outsized outcomes," he says. “That’s why the flip."

For the IIT-Delhi grad, Blinkit is another homecoming of sorts: From value to convenience. Before morphing into Blinkit, Grofers found its niche in Tier II and beyond. It was a company rooted in offering more bang for every buck to its users, largely in Tier II and beyond. From its EDLP (every-day low prices) to private labels, Dhindsa was wooing consumers in Bharat who were slowly gravitating towards ecommerce.

![]() In 2018, the company was eyeing half of its sales from own brands ‘HaveMore’ and ‘SaveMore’, which catered to price-sensitive consumers. “Our focus is to service what we call the ‘Real Bharat’," says Dhindsa. The Real Bharat, he explains, was largely the two-wheeler families who were yet to experience the world of ecommerce. “Our target is to bring the next 100 million new customers to ecommerce."

In 2018, the company was eyeing half of its sales from own brands ‘HaveMore’ and ‘SaveMore’, which catered to price-sensitive consumers. “Our focus is to service what we call the ‘Real Bharat’," says Dhindsa. The Real Bharat, he explains, was largely the two-wheeler families who were yet to experience the world of ecommerce. “Our target is to bring the next 100 million new customers to ecommerce."

A year later, Dhindsa stayed committed to his vision. “We are clear about our target audience," he said in an interview in May 2019. “It is going to be middle India that goes after planned purchases and low-priced offerings," he said and reiterated the value proposition of Grofers, which had a presence across two dozen cities by the end of 2019.

Cut to 2022. Blinkit, the new avatar of Grofers, has brought Dhindsa back to Delhi, and top eight cities, and a new set of consumers who are not deal hunters but convenience seekers. “Now people don’t want ‘coming soon’. It has to be ‘coming now’," he says.

Delhi businessman Alok Gupta uses quick commerce to place an order for his paan from the local betel shop every night. “I need one after dinner and I get it quick," he says. “It adds more pleasure to my Netflix viewing."

Marketing experts link the rise of the Netflix generation with that of instant consumerism. “It all started with Maggi," contends Ashita Aggarwal, marketing professor at SP Jain Institute of Management and Research. The two-minute noodles seeded the idea of quick food, and quick consumption. Then came a bunch of global QSR (quick service restaurant) players like McDonald’s and KFC who whetted the appetite of Indians with burgers and fries. “They too were quick but inside the restaurant," she quips. Interestingly, the 90s was when Indians were slowly warming up to the idea of ordering food for in-home consumption.

There was a problem, though. “The food delivery by QSR players was fast, not quick," points put Aggarwal. Waiting for the food for close to an hour or so spoilt the fun of ordering. Pizza player Domino’s changed the game with its ‘30-minute delivery or free pizza’ promise.

![]()

![]() In 2007, Indians woke up to a new form of quick entertainment in sport—the T20 World Cup. India winning the inaugural edition coincided with an era of Indians becoming restless, exhibiting little patience and yearning for more bang for every buck. Smartphone adoption and internet penetration created a fertile ground for startups promising quick fixes in all walks of life. Online shopping to online delivery to online entertainment, everything grew at a rapid clip.

In 2007, Indians woke up to a new form of quick entertainment in sport—the T20 World Cup. India winning the inaugural edition coincided with an era of Indians becoming restless, exhibiting little patience and yearning for more bang for every buck. Smartphone adoption and internet penetration created a fertile ground for startups promising quick fixes in all walks of life. Online shopping to online delivery to online entertainment, everything grew at a rapid clip.

Though fast might be fun for consumers, for quick commerce founders, it brings its own set of challenges. The biggest is unit economics. Ankur Bisen, senior vice president (retail & consumer products division) at consulting firm Technopak, sounds a word of caution. “How will you make money?" he asks.

The average order value is tiny, and doesn’t make sense. The second problem is lack of differentiation. “If quick delivery is the only differentiator, then will it lead to customer stickiness?" he asks. The third problem is with the limited play of quick commerce. “It’s a largely urban phenomenon and would likely stay confined to top cities," he adds. That food delivery players are getting into quick commerce, Bisen adds, also speaks about their inability to widen the food delivery play. The grocery business, he maintains, is not an easy one. BigBasket got acquired by Tatas and Dunzo reportedly has been bleeding heavily—a ₹225.7 crore loss on operating revenue of ₹45.8 crore in FY21. “Nobody has ever made money," he adds.

Zomato’s founder, for his part, sounds optimistic. “Four years ago, we used to hear that food delivery will never make money. Now it does," smiles Deepinder Goyal, adding that there is always a first time. “If history was the only thing that ever happened, then nothing new would have ever happened." Perhaps it is their ‘instant’ chemistry that Goyal and Dhindsa are counting on to rewrite the history of Indian food delivery and quick commerce.

(Left)Deepinder Goyal, Founder and CEO, Zomato and Albinder Dhindsa, Founder, Blinkit

(Left)Deepinder Goyal, Founder and CEO, Zomato and Albinder Dhindsa, Founder, Blinkit

Meanwhile, Dhindsa’s struggle to raise funds continued. For investors, hyperlocal grocery had become a two-player race, and there was no meaningful growth. “For them, the question was why to put money here versus other segments which were more promising," he recounts. Dhindsa doesn’t blame the investors. “They too have their skin in the game and didn’t have any incentive to leave their portfolio company to die." At different points in time, he stresses, Grofers had different investors. “At some point, the same set of people backed out. Now, you can’t take it personally."

Meanwhile, Dhindsa’s struggle to raise funds continued. For investors, hyperlocal grocery had become a two-player race, and there was no meaningful growth. “For them, the question was why to put money here versus other segments which were more promising," he recounts. Dhindsa doesn’t blame the investors. “They too have their skin in the game and didn’t have any incentive to leave their portfolio company to die." At different points in time, he stresses, Grofers had different investors. “At some point, the same set of people backed out. Now, you can’t take it personally." In 2018, the company was eyeing half of its sales from own brands ‘HaveMore’ and ‘SaveMore’, which catered to price-sensitive consumers. “Our focus is to service what we call the ‘Real Bharat’," says Dhindsa. The Real Bharat, he explains, was largely the two-wheeler families who were yet to experience the world of ecommerce. “Our target is to bring the next 100 million new customers to ecommerce."

In 2018, the company was eyeing half of its sales from own brands ‘HaveMore’ and ‘SaveMore’, which catered to price-sensitive consumers. “Our focus is to service what we call the ‘Real Bharat’," says Dhindsa. The Real Bharat, he explains, was largely the two-wheeler families who were yet to experience the world of ecommerce. “Our target is to bring the next 100 million new customers to ecommerce."

In 2007, Indians woke up to a new form of quick entertainment in sport—the T20 World Cup. India winning the inaugural edition coincided with an era of Indians becoming restless, exhibiting little patience and yearning for more bang for every buck. Smartphone adoption and internet penetration created a fertile ground for startups promising quick fixes in all walks of life. Online shopping to online delivery to online entertainment, everything grew at a rapid clip.

In 2007, Indians woke up to a new form of quick entertainment in sport—the T20 World Cup. India winning the inaugural edition coincided with an era of Indians becoming restless, exhibiting little patience and yearning for more bang for every buck. Smartphone adoption and internet penetration created a fertile ground for startups promising quick fixes in all walks of life. Online shopping to online delivery to online entertainment, everything grew at a rapid clip.