How edtech startup Eruditus entered the unicorn club

The firm rocked the edtech charts by making Ivy League education accessible and affordable to executives across the globe

Ashwin Damera, Co-Founder and CEO, Eruditus

Ashwin Damera, Co-Founder and CEO, Eruditus

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur

It was around the fag end of 2016. Over a decade after completing an MBA from Harvard Business School (HBS), Ashwin Damera was readying to learn something crucial, which he probably skipped during his Ivy League stint: The power of zero, value and valuation. The guy imparting the lesson to the chartered accountant was a familiar face. “Are you missing a zero?" Damera’s HBS batchmate quipped after a quick scan of his investor pitch. “You closed last fiscal at $7 million in revenue, now you are close to $10 million in FY17, and you have a target of $50 million over the next two years. It’s quite impressive," he observed. “But are you sure you are not missing a zero?"

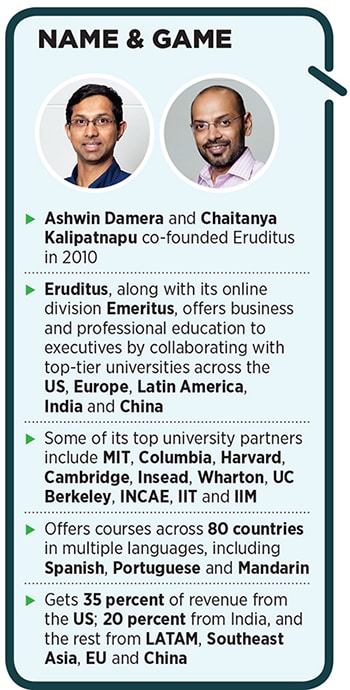

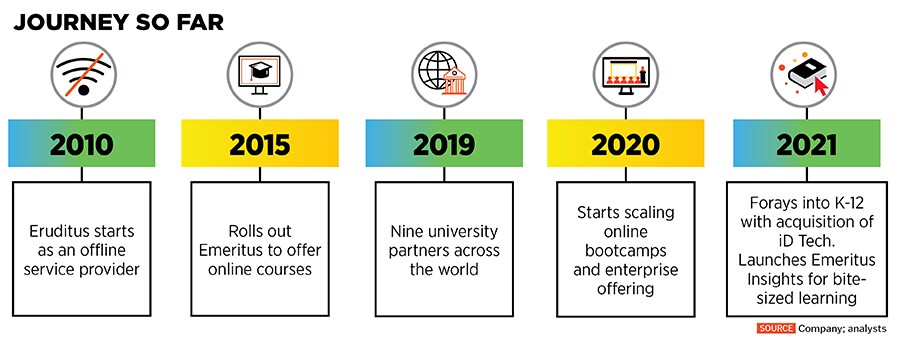

Damera had the air of man who knew his numbers. “No" was the emphatic reply from the co-founder of Eruditus, which he started in 2010 with Chaitanya Kalipatnapu as an offline venture offering executive education courses in collaboration with global universities. For the first five years, the startup remained bootstrapped and profitable.

The batchmate wasn’t convinced and persisted with the need “to add an extra zero". “Use an Excel sheet. I will teach you how to add a zero to $50 million," he smiled.

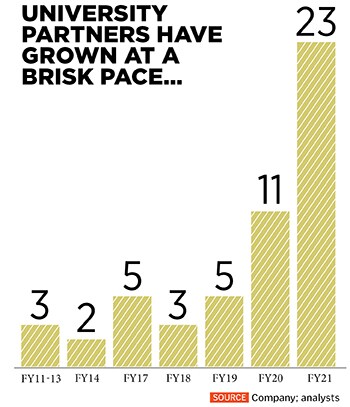

The lesson started. The first hack was to inflate the number of universities that Eruditus works with. From 10, take it to 50 was the counsel. The number of courses per university, the friend pointed out, should be doubled to 40 instead of 20. The average size per batch too must be doubled to 200. And last, and certainly not least, bump up the price per batch. “That’s how your target becomes $500 million, and you get more value," was the priceless wisdom. Damera was shocked. “This is not right at all," he exclaimed.

A year back, in 2015, close to two dozen investors exuded the same emotion when Damera reached out to them for his maiden, and meagre, fund raise of $2 million. “This is not right at all," venture capitalists (VC) screeched, alluding to the business model. In fact, the way Damera was running the business was nothing less than horrific for them. “Are you a promoter or an entrepreneur?" asked a funder. How can a person, he tried to fathom, run a business for five years and still own 100 percent equity.

A year back, in 2015, close to two dozen investors exuded the same emotion when Damera reached out to them for his maiden, and meagre, fund raise of $2 million. “This is not right at all," venture capitalists (VC) screeched, alluding to the business model. In fact, the way Damera was running the business was nothing less than horrific for them. “Are you a promoter or an entrepreneur?" asked a funder. How can a person, he tried to fathom, run a business for five years and still own 100 percent equity.

Damera explained that the venture didn’t need much capital that Eruditus has been profitable and that the startup never felt the need to scale. Now that the venture is going online, he underlined, there is a need for capital to expand. The argument didn’t cut much ice. “I don’t think your business can ever have a high valuation," was the VC’s snub.

Interestingly, Damera did have a fleeting tryst with a heady valuation a decade back. Travelguru, the first venture he co-founded in 2005, was all set to be bought by global travel giant Expedia in 2008. The money on the table had multiple zeroes: 25x of the net revenue. The due diligence was in the last stage, and then the dream turned into a nightmare.

Lehman Brothers collapsed in 2008. The global markets crashed, and Expedia nixed its acquisition plan. A year later, Damera sold the company to Travelocity at one-fifth of what Expedia had offered. “I believe that some of life’s best lessons come the hard way," philosophises the founder.

Fast forward to 2021. The power of zero, value and valuation revisits Damera. This time, though, all three come together in a much potent and rewarding form for the entrepreneur. Over a decade, he has built an enviable roster of university partners such as MIT, Columbia, Harvard, Cambridge, INSEAD, Wharton, UC Berkeley, INCAE, IIT and IIM, offers courses across 80 countries in multiple languages such as Spanish, Portuguese and Mandarin and gets 35 percent of its revenue from the US.

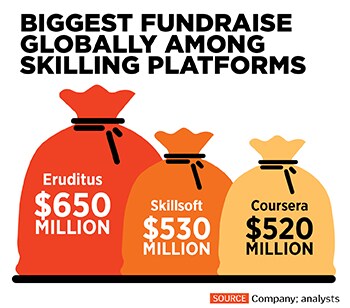

In August, Eruditus raised $650 million in a Series E round led by Accel and SoftBank Vision Fund II at a valuation of $3.2 billion. The round not only catapulted the startup into the unicorn league, but it also made Eruditus the third biggest edtech player in India after Byju’s and Unacademy.

In August, Eruditus raised $650 million in a Series E round led by Accel and SoftBank Vision Fund II at a valuation of $3.2 billion. The round not only catapulted the startup into the unicorn league, but it also made Eruditus the third biggest edtech player in India after Byju’s and Unacademy.

The valuation surged from $30 million in 2016 to $400 million in 2019, then to $800 million a year later and now four times that. Two of the investors in the present round, Damera claims, refused to back the company during its early days. One of them didn’t find the business model disruptive. “We are outwardly ambitious people, but inwardly modest," he says, declining to identify the fund. While $430 million in the Series E round is in the form of primary capital, the rest is secondary. “Our primary and secondary happen at the same price," he proudly says. “We never inflate valuation."

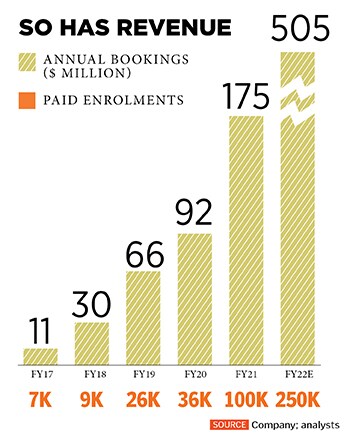

Eruditus’s story would be grossly incomplete unless one adds another column next to the valuation table in the excel sheet: The heady revenue curve—from $11 million in FY17 to $66 million in FY19 and $175 million in FY21. And now the revenue target is $505 million for the next fiscal. In three years, Damera lets on, Eruditus should cross $1 billion in revenue. “We have had crazy growth," he says.

Eruditus’s story would be grossly incomplete unless one adds another column next to the valuation table in the excel sheet: The heady revenue curve—from $11 million in FY17 to $66 million in FY19 and $175 million in FY21. And now the revenue target is $505 million for the next fiscal. In three years, Damera lets on, Eruditus should cross $1 billion in revenue. “We have had crazy growth," he says.

In the mid-2000s, Damera’s outlook to capital was different, even as Travelguru had to go head-on with deeper-pocketed rivals like MakeMyTrip, Cleartrip and Yatra. “I didn’t realise at that point that capital raising could be a competitive advantage," he laughs. Though the first-generation entrepreneur raised around $25 million and counted Sequoia and Battery Venture among his backers, it was not sufficient to match the might of the other online travel giants.

“If raising crazy money is your moat, you are dead," reckons Damera, Eruditus’s current valuation notwithstanding. That learning came in handy when he launched the edtech venture in 2010. “I wanted to build a business where fundamental unit economics are strong," he says. Though the offline venture didn’t scale much and grew at a sedate pace for the first five years, it had nothing to do with Damera’s risk appetite. “I’m very conservative. But when it comes to the business, there’s ambition," he says.

It was at HBS that Damera discovered his risk-taking appetite and ambition. “That changed my life." After working with Citibank for four years, he decided on an MBA at HBS. Damera took a loan of about $120,000 in 2003. “My grandfather gave me $10,000 (then around ₹4.5 lakh)," he recalls. With the money, his grandpa dished out a once-in-a-lifetime advice: Have fun and come back.

In the summer of 2004, between his first and second year, Damera got into Booz Allen’s London office for a two-and-a half-month internship. The salary on offer was an astounding $20,000. At the same time, another opportunity of working as an intern for the CEO of American airline JetBlue popped up. The remuneration was a measly $10 daily wage. He opted for New York. “I lost money in the city," he recounts, but with few regrets. Reason: Damera now aspired to become a CEO. “I didn’t want to be a consultant," he says, His role as an intern was simple: To shadow the CEO. From meeting clients to lobbying with high-ranked government officials, Damera was the proverbial fly on the wall of corporate corridors taking in all that he saw and heard.

In the summer of 2004, between his first and second year, Damera got into Booz Allen’s London office for a two-and-a half-month internship. The salary on offer was an astounding $20,000. At the same time, another opportunity of working as an intern for the CEO of American airline JetBlue popped up. The remuneration was a measly $10 daily wage. He opted for New York. “I lost money in the city," he recounts, but with few regrets. Reason: Damera now aspired to become a CEO. “I didn’t want to be a consultant," he says, His role as an intern was simple: To shadow the CEO. From meeting clients to lobbying with high-ranked government officials, Damera was the proverbial fly on the wall of corporate corridors taking in all that he saw and heard.

What also instilled loads of confidence in the young man was that he was rubbing shoulders with his classmates who had been there, done that. “Alexander Samwer was my classmate," Damera claims. Samwer, along with his brothers, started tech incubator Rocket Internet. “He was sitting next to me." Jeremy Stoppelman, who started Yelp, was another contemporary. “These were smart guys. But I realised I was equally smart in class. Harvard gave me the confidence," he says.

Confidence gave birth to bold ambition. At a Harvard business plan contest, Damera finished runner-up with his idea of Travelguru. At the same time, destiny played another trick to check his risk appetite. He got a job offer from McKinsey in New York. Only a crazy person would have turned down a salary of $175,000 per annum, plus a signing bonus of $15,000. “Imagine, I am a guy with student debt to pay off, and I declined," he says. His parents, understandably, had a different take. “Why can’t you be like your brother?" was the question when he broke the news that he had decided to come back to India. “Take up the job, pay back the loan and then do whatever you want," his parents advised.

Confidence gave birth to bold ambition. At a Harvard business plan contest, Damera finished runner-up with his idea of Travelguru. At the same time, destiny played another trick to check his risk appetite. He got a job offer from McKinsey in New York. Only a crazy person would have turned down a salary of $175,000 per annum, plus a signing bonus of $15,000. “Imagine, I am a guy with student debt to pay off, and I declined," he says. His parents, understandably, had a different take. “Why can’t you be like your brother?" was the question when he broke the news that he had decided to come back to India. “Take up the job, pay back the loan and then do whatever you want," his parents advised.

Damera, though, wanted to live his dream of becoming a CEO. One of his friends at HBS offered him $200,000 in funding. Damera took a leap of faith. “There was an opportunity," he says.

Almost two decades after HBS, the pandemic has offered Damera another opportunity. The world has gone online, education has morphed into a digital avatar, and the digital landscape across the globe has transformed. “Now we can use VC money to fund profitable growth," he says, explaining how his global business is shaping up. This year, the Latin American business will clock around $80 million in revenue. “Two years back, it was just $2 million," he says. China, he adds, will contribute another $20-25 million.

The backers are delighted with the way Eruditus has been making high quality education accessible and affordable. “We have known Ashwin and the team at Eruditus for a number of years," says Anand Daniel, partner at Accel. What has been impressive, he explains, is the approach and execution. The platform puts Eruditus and its partner universities at the forefront of a revolution in higher education. “Their products are helping bring the best quality education around the world at affordable prices," adds Daniel.

Damera is in no mood to get carried away by the accolades. He has a different lens to look at zero, value and valuation. “I always focus on input metrics," he says. Just because a company is valued at $3.2 billion, he adds, it doesn’t make it successful. Damera is now charting a bold global plan to expand at a furious pace.

Would that mean burning more cash? He explains the difference between good and bad burn. If what one is burning includes money spent on people, technology and capex, then it’s okay. The company, he shares, will spend around $30 million in creating courses this year. “We don’t do cashbacks, discounts, or buy this and get a pizza free," he smiles, adding that the company has always been gross margin positive. “We are not profitable, but could have been in FY21," he says. The company decided to invest in growth. “But we will be profitable in FY22," he claims.

Though Damera is elated with the valuation and the sustainable growth of Eruditus, what keeps him happy is a constant realisation of the biggest learning during his decade-long journey. “The best form of fundraising," he underlines, “is from customers. It’s not from venture capitalists."

First Published: Sep 06, 2021, 10:20

Subscribe Now