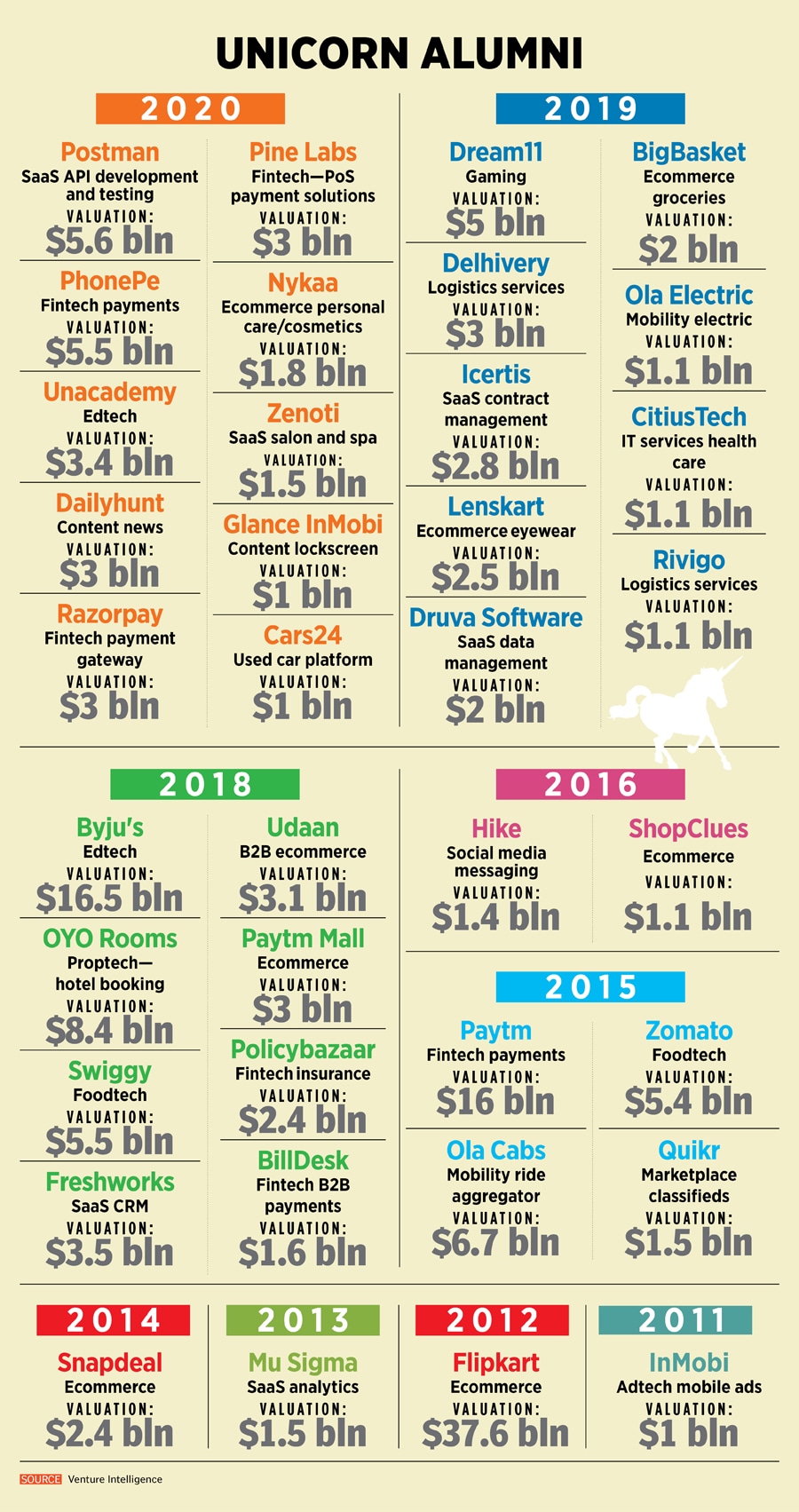

Five years later in Bengaluru, Prem Pavoor was witnessing the birth of more unicorns. “We saw a few companies getting to a billion-dollar valuation," recalls the partner and head of India at Eight Roads Ventures, a VC fund that backs growth-stage firms. In 2016, India had five unicorns in the elite club—a breakout moment considering that between 2011 and 2015, the country had produced six unicorns.

Fast forward to 2021. It’s a déjà vu moment for Depura, who has now joined the party. Mindtickle is one of the 26 unicorns that have emerged in just eight months this year. Depura first mimics the reaction of the people who are flabbergasted with the charge of unicorns. “It is like, OMG! Every Tom, Dick and Harry is becoming a unicorn," he says. The common sentiment echoing, he adds, is like “arey iska bhi ho gaya, uska bhi ho gaya, hum bhi kar lete toh hamara bhi ho jaata… (everybody is becoming a unicorn. Had we tried, we would have also become one)."

Depura is at pains to point out that it “didn’t happen overnight". It took Mindtickle 10 years to get to the prized valuation. Ditto with most of the other unicorns, which have slogged for years. Some of them, adds Depura, have been there for seven, eight, nine years, and had been silently working. Now when people see unicorns raining, they think it’s a sudden thing. “It’s not," smiles Depura, who uses the analogy of a bamboo to explain the unicorn rush. Nobody notices bamboos during their formative years. They grow, but stay under the radar. And suddenly, one fine day they just shoot through the roof, and start getting attention. “Startups are like bamboos," he smiles.

![]()

Investors who have been driving the charge see a method in the mania. “Everyone is positively surprised and elated by the number and pace of unicorns," smiles Pavoor. Online health and medicine delivery platform PharmEasy one of the unicorns this year, counts Eight Roads Ventures among its backers. While the US and China, explains Pavoor, have been in a sustained bull market on the private side for a few years, India is now witnessing a similar bullishness. “I’m happy to see that," he says, trying to break down the hysteria and hype around unicorns.

![]() The investor starts with a hard-hitting Q&A session. Are the valuations high? “Indeed, some of them are. There is no denying that," he says. Second question: Are people giving value for future promise and potential of each of these companies? “Of course, they are. It’s also the truth," he underlines. Third: Is this for real? “Indeed it is. It’s not an aberration," he asserts. And lastly, what next for the unicorns? “More unicorns, IPO, mergers and acquisitions, and more growth—sustainable growth."

The investor starts with a hard-hitting Q&A session. Are the valuations high? “Indeed, some of them are. There is no denying that," he says. Second question: Are people giving value for future promise and potential of each of these companies? “Of course, they are. It’s also the truth," he underlines. Third: Is this for real? “Indeed it is. It’s not an aberration," he asserts. And lastly, what next for the unicorns? “More unicorns, IPO, mergers and acquisitions, and more growth—sustainable growth."

Pavoor explains the reason behind the downpour of unicorns. He starts with the supply side. First, low interest rates in the US, with the Federal Reserve printing money, has created excess liquidity. What this means is an abundant supply of capital and dry powder for most venture capitalists and private equity managers. This trend has coincided with a rise in high-quality startups. Second, as public markets continue to stay buoyant, it has resulted in bumper gains for investors, hedge funds and family offices. “They are the new breed of super-angels and investors in all these startups," he says.

It’s a matter of a few years, reckon VCs, by when India will see the next big thing in the startup space: The decacorn, or ventures with a valuation of $10 billion-plus. So far, India has two of them in Byju’s and Paytm with valuations of $21 billion and $15.6 billion, respectively, according to private market intelligence platform Tracxn.

GV Ravishankar, managing director at Sequoia India, explains why unicorns won’t remain highly aspirational. “Things that are rare will remain an aspiration," he says, adding that as the unicorn tag becomes less rare, startups will aspire to be decacorns. And then the herd mentality will come into play. At times, he points out, it is also about someone showing the way, and then more startups aspiring to reach there. “We should expect to see more decacorns," he says.

![]()

That journey may well have picked up pace. Consider, for instance, Postman, one of the world’s top API development platforms, which bagged $225 million in a Series D round of funding at a valuation of $5.6 billion. Founded in Bengaluru and headquartered out of San Francisco, Postman—which turned unicorn last year—claims to have over 17 million users and 5 lakh organisations on its platform.

![]() Along with decacorns, another trend to emerge strongly is startups taking the primary market route with initial public offerings (IPOs). Those with a revenue of $100 million are more likely to hit the public market as companies in such a revenue bracket have a more predictable growth, reasonable unit economics and are either profitable or have a path to profitability. Alongside, secondary exits will continue to remain a healthy way to exit as larger funds look to invest in market-leading companies. “Markets decide valuations," says Ravishankar, underlining that in a buoyant market, more companies will benefit from rich valuations. But companies, he stresses, don’t become unicorns without exhibiting leadership in their segment or through scale or growth.

Along with decacorns, another trend to emerge strongly is startups taking the primary market route with initial public offerings (IPOs). Those with a revenue of $100 million are more likely to hit the public market as companies in such a revenue bracket have a more predictable growth, reasonable unit economics and are either profitable or have a path to profitability. Alongside, secondary exits will continue to remain a healthy way to exit as larger funds look to invest in market-leading companies. “Markets decide valuations," says Ravishankar, underlining that in a buoyant market, more companies will benefit from rich valuations. But companies, he stresses, don’t become unicorns without exhibiting leadership in their segment or through scale or growth.

So, what has changed for the unicorns of India? How are they different from their predecessors who entered the hallowed club, say, five or six years ago? Is the new crop highly differentiated? Shubhankar Bhattacharya, general partner at global VC firm Foundamental, points out one dominant external factor that has resulted in the charge of the unicorns: Covid-19. The pandemic has accelerated the adoption of technology and tech-enabled business models. Firms with a product-market fit are scaling faster than ever, allowing them to tap into large profit pools with maturing unit economic models. “When this surge in tech adoption meets an over-abundance of capital, you get a dramatic rise in unicorns," he says.

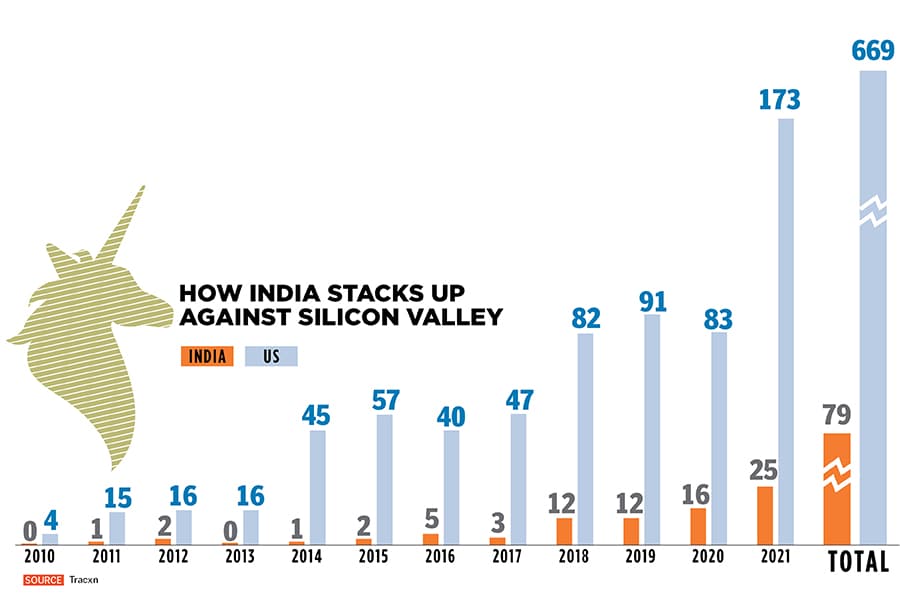

![]() The trend is not confined to India. Look at Silicon Valley. After seeing a dip from a high of 57 unicorns in 2015 to 47 two years later, the numbers have seen a heady growth since then. While last year, the US had 83 unicorns, the number for the first eight months this year has shot up to 173.

The trend is not confined to India. Look at Silicon Valley. After seeing a dip from a high of 57 unicorns in 2015 to 47 two years later, the numbers have seen a heady growth since then. While last year, the US had 83 unicorns, the number for the first eight months this year has shot up to 173.

Back in India, Pavoor of Eight Roads Ventures contends that the DNA of Indian founders and their ventures has also undergone a seminal transformation.

“What is different this time is that there is some reality under the hood," he says, adding that the pandemic tailwind has helped in shaping up real business models, real companies and real traction. A strong performance of edtech, B2B, fintech and SaaS (software as a service) unicorns over the last two years reinforces the fact that these companies are making the most of the opportunity. “This time, investors too are looking for unit economics," he says.

In Bengaluru, Sujeet Kumar, co-founder of B2B ecommerce unicorn Udaan, reckons that the startup ecosystem has matured in India. “Who talks about GMV (gross merchandise value) these days?" he asks. The focus now is on unit metrics, sustainable business and how well one uses funding to keep growing.

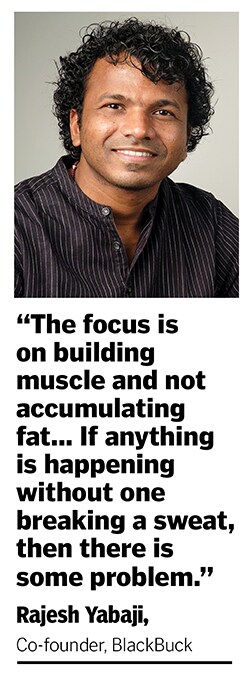

Rajesh Yabaji, who co-founded B2B trucking platform BlackBuck in 2015, agrees. “The focus is on building muscle and not accumulating fat," he says. BlackBuck is from the unicorn batch of 2021. The founders are aware of the thumb rule that anything that comes easy doesn’t stay. “If anything is happening without one breaking a sweat, then there is some problem," he asserts, adding that one must not get distracted by the noise around unicorns, valuation and funding.

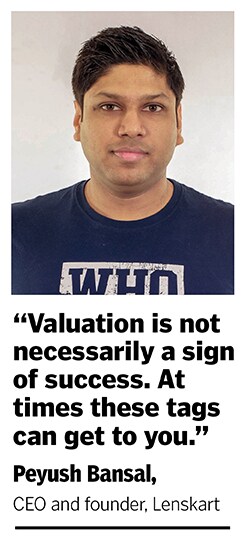

![]() Peyush Bansal sounds a word of caution. “Valuation is not necessarily a sign of success," says the founder and CEO of Lenskart, which turned unicorn in 2019 and is now reportedly valued at $2.5 billion. Bansal explains why it is crucial to stay grounded. “At times these tags can get to you," he says, questioning if being valued at over a billion dollars has anything to do with the value that an entrepreneur is creating. The sign of success, he underlines, is when the company is generating value for shareholders and building a brand for customers.

Peyush Bansal sounds a word of caution. “Valuation is not necessarily a sign of success," says the founder and CEO of Lenskart, which turned unicorn in 2019 and is now reportedly valued at $2.5 billion. Bansal explains why it is crucial to stay grounded. “At times these tags can get to you," he says, questioning if being valued at over a billion dollars has anything to do with the value that an entrepreneur is creating. The sign of success, he underlines, is when the company is generating value for shareholders and building a brand for customers.

Ashwin Damera, for sure, asserts that he has been creating immense value for his employees, around 1,400 of them across Mumbai, New Delhi, Shanghai, Singapore, Palo Alto, Mexico City, Boston, New York, London and Dubai. “Valuation is good because it creates wealth," asserts the co-founder of Eruditus, the third-largest valued edtech payer in India after Byju’s and Unacademy. In August, Eruditus raised $650 million in a Series E round of funding led by Accel and SoftBank Vision Fund II at a valuation of $3.2 billion, a heady jump from the $800-million valuation last year.

Damera explains why multi-billion valuations matter. “As a metric, 15 percent of our cap table is owned by the employee," he informs. What this means is that because of the latest round of funding, employees will have about $450 million (about ₹3,000 crore) of value. If the company manages to grow at least 3x in the next two years, it would end up creating ₹10,000 crore of value for employees. “That’s very meaningful. So the valuation absolutely matters," he says, although he is quick to qualify the valuation game. “It only makes sense if the business has good unit metrics, is sustainable, and the moat that has been built is defensible."

![]()

For shareholders and stakeholders, a hefty valuation matters without a doubt, but it may often come with a heavy price that a founder ends up paying. Pavoor of Eight Roads Ventures discusses the flip side. “Right now, we are in a bull market," he says. But when liquidity flatlines—or starts reducing—will these companies manage to keep the pace of growth going?

![]() The fear of unicorpses—dead unicorns—might also loom large once the strong funds flow begins to ebb. Take, for instance, what happened in the US towards the end of 2015 and 2016. The bullishness got tempered, lofty valuations became a thing of the past, and fund managers started writing down their investments. Marc Benioff, founder and chief executive of Salesforce, raised the red flag. “There are going to be lots of dead unicorns," he reportedly said at the World Economic Forum in Davos in 2016. Some did fail, and from a high of 57 unicorns in 2015, new additions dipped to 40 in 2016, according to data shared by Tracxn.

The fear of unicorpses—dead unicorns—might also loom large once the strong funds flow begins to ebb. Take, for instance, what happened in the US towards the end of 2015 and 2016. The bullishness got tempered, lofty valuations became a thing of the past, and fund managers started writing down their investments. Marc Benioff, founder and chief executive of Salesforce, raised the red flag. “There are going to be lots of dead unicorns," he reportedly said at the World Economic Forum in Davos in 2016. Some did fail, and from a high of 57 unicorns in 2015, new additions dipped to 40 in 2016, according to data shared by Tracxn.

Back in India, VCs reckon that founders must be guarded in their approach. It holds true especially for those who have seen crazy jumps in valuation. When you skip the normal road and go aerial, you also skip the lessons that you would have otherwise learnt on the course. “That’s the biggest threat," says a VC on condition of anonymity. The risk is not failing, but not learning and, therefore, failing.

Ravishankar of Sequoia too tempers the excitement. Companies, he stresses, may be less ready to deal with the burden of the significant capital they have raised. “Not every company that’s highly valued remains highly valued," he says, adding that some failures will be inevitable. “Being a unicorn is not a sign of an enduring business," he points out. The journey from success to endurance is a long one. “Few companies will become enduring franchise businesses," he says. Yet the flip side must not deter founders from thinking big. “Entrepreneurship is inherently risky, but without that risk there will be no greatness either."

In 2016, India had five unicorns in the elite club—a breakout moment considering that between 2011 and 2015, the country had produced six unicorns

In 2016, India had five unicorns in the elite club—a breakout moment considering that between 2011 and 2015, the country had produced six unicorns

The investor starts with a hard-hitting Q&A session. Are the valuations high? “Indeed, some of them are. There is no denying that," he says. Second question: Are people giving value for future promise and potential of each of these companies? “Of course, they are. It’s also the truth," he underlines. Third: Is this for real? “Indeed it is. It’s not an aberration," he asserts. And lastly, what next for the unicorns? “More unicorns, IPO, mergers and acquisitions, and more growth—sustainable growth."

The investor starts with a hard-hitting Q&A session. Are the valuations high? “Indeed, some of them are. There is no denying that," he says. Second question: Are people giving value for future promise and potential of each of these companies? “Of course, they are. It’s also the truth," he underlines. Third: Is this for real? “Indeed it is. It’s not an aberration," he asserts. And lastly, what next for the unicorns? “More unicorns, IPO, mergers and acquisitions, and more growth—sustainable growth."

Along with decacorns, another trend to emerge strongly is startups taking the primary market route with initial public offerings (IPOs). Those with a revenue of $100 million are more likely to hit the public market as companies in such a revenue bracket have a more predictable growth, reasonable unit economics and are either profitable or have a path to profitability. Alongside, secondary exits will continue to remain a healthy way to exit as larger funds look to invest in market-leading companies. “Markets decide valuations," says Ravishankar, underlining that in a buoyant market, more companies will benefit from rich valuations. But companies, he stresses, don’t become unicorns without exhibiting leadership in their segment or through scale or growth.

Along with decacorns, another trend to emerge strongly is startups taking the primary market route with initial public offerings (IPOs). Those with a revenue of $100 million are more likely to hit the public market as companies in such a revenue bracket have a more predictable growth, reasonable unit economics and are either profitable or have a path to profitability. Alongside, secondary exits will continue to remain a healthy way to exit as larger funds look to invest in market-leading companies. “Markets decide valuations," says Ravishankar, underlining that in a buoyant market, more companies will benefit from rich valuations. But companies, he stresses, don’t become unicorns without exhibiting leadership in their segment or through scale or growth. The trend is not confined to India. Look at Silicon Valley. After seeing a dip from a high of 57 unicorns in 2015 to 47 two years later, the numbers have seen a heady growth since then. While last year, the US had 83 unicorns, the number for the first eight months this year has shot up to 173.

The trend is not confined to India. Look at Silicon Valley. After seeing a dip from a high of 57 unicorns in 2015 to 47 two years later, the numbers have seen a heady growth since then. While last year, the US had 83 unicorns, the number for the first eight months this year has shot up to 173. Peyush Bansal sounds a word of caution. “Valuation is not necessarily a sign of success," says the founder and CEO of Lenskart, which turned unicorn in 2019 and is now reportedly valued at $2.5 billion. Bansal explains why it is crucial to stay grounded. “At times these tags can get to you," he says, questioning if being valued at over a billion dollars has anything to do with the value that an entrepreneur is creating. The sign of success, he underlines, is when the company is generating value for shareholders and building a brand for customers.

Peyush Bansal sounds a word of caution. “Valuation is not necessarily a sign of success," says the founder and CEO of Lenskart, which turned unicorn in 2019 and is now reportedly valued at $2.5 billion. Bansal explains why it is crucial to stay grounded. “At times these tags can get to you," he says, questioning if being valued at over a billion dollars has anything to do with the value that an entrepreneur is creating. The sign of success, he underlines, is when the company is generating value for shareholders and building a brand for customers.

The fear of unicorpses—dead unicorns—might also loom large once the strong funds flow begins to ebb. Take, for instance, what happened in the US towards the end of 2015 and 2016. The bullishness got tempered, lofty valuations became a thing of the past, and fund managers started writing down their investments. Marc Benioff, founder and chief executive of Salesforce, raised the red flag. “There are going to be lots of dead unicorns," he reportedly said at the World Economic Forum in Davos in 2016. Some did fail, and from a high of 57 unicorns in 2015, new additions dipped to 40 in 2016, according to data shared by Tracxn.

The fear of unicorpses—dead unicorns—might also loom large once the strong funds flow begins to ebb. Take, for instance, what happened in the US towards the end of 2015 and 2016. The bullishness got tempered, lofty valuations became a thing of the past, and fund managers started writing down their investments. Marc Benioff, founder and chief executive of Salesforce, raised the red flag. “There are going to be lots of dead unicorns," he reportedly said at the World Economic Forum in Davos in 2016. Some did fail, and from a high of 57 unicorns in 2015, new additions dipped to 40 in 2016, according to data shared by Tracxn.