CityMall wants to change how small-town India buys groceries

Founders Angad Kikla and Naisheel Verdhan are building a network of micro-entrepreneurs in smaller cities and towns, and aim to touch 400 cities

From left: Angad Kikla and Naisheel Verdhan, Co-Founders of CityMall at their warehouse in Basai Dhankot village (Gurugram District) Image Credits: Amit Verma[br]

Sunita Yadav is a school teacher in a village called Tint, about two and a half hours by car west of Delhi, in Haryana. The closest city is Rewari, some 15 km away. A friend told Yadav about CityMall, “a digital app” as she called it, and she signed up last September.

Yadav (44) is also a mother of two, and offers private tuitions to help run her household and pay for her sons’ education. And CityMall, a community networking-based online commerce app, adds about Rs 15,000 a month to her income, from the commission and incentives she makes, selling mostly groceries to her friends and neighbours. She has 50 to 60 households that are regular customers, placing orders on a daily, weekly or bi-weekly basis.

CityMall’s founders Angad Kikla and Naisheel Verdhan, both engineers by training and repeat entrepreneurs, have added some ‘gamification’ to the app—popular startup parlance for providing incentives for users to do more, similar to how certain achievements in video games can open rewards or new levels and so on for players.

In Yadav’s case, she has already cracked some three or four levels—based on the number of customers she has brought in and the sales she has notched up—and is a proud ‘silver director’ among CityMall’s micro-entrepreneur partners, all of whom are called ‘community leaders’ by the founders. Kikla and Verdhan started the venture in early 2019, but the current model of building a social commerce network around community leaders is only a little over a year old, because the duo first experimented with getting customers to buy in groups through WhatsApp.

They were also selling ‘long-tail’ products, such as cheap hair curlers imported from China. The ‘Aha’ moment happened when they realised that a packet of Maggi instant noodles was way easier to sell to more people and at a higher frequency. From there, it was only a few steps more to shifting focus to groceries, converting some of the group buying customers into community leaders, and offering them an income via commissions instead of savings on purchases.

Today CityMall has some 20,000 community leaders in eight smaller cities and towns—Rewari, Dharuhera, Pataudi, Sonipat, Bahadurgarh, Jhajjar, Rohtak and Panipat. Using the app, they aggregate orders from their local communities and CityMall ships the products to them the next day the community leaders then deliver the goods to the end-customers or the customers collect it from the leaders.

“We aim to put a lot of data analytics in the hands of the community leaders to help them become successful micro-entrepreneurs,” says Kikla. Over a period of time, the data from the app and the analytics from CityMall help the community leaders understand who their top customers are, or who might want to leave they can also figure out what they can up-sell and cross-sell.

There is also an app for end-consumers, although they can always just send their shopping lists through WhatsApp. Over a period of time, however, most people are converted to the idea of using the app to place their orders, says Kikla. This is because of a combination of superior cataloguing that’s possible on the app, compared to WhatsApp, and the gentle nudging from the community leaders. There are over 3,000 products on offer on CityMall, and when individuals place orders through the app, they automatically get aggregated on the community leader’s app.

The consumer app is about 16 MB to download on Google’s Play store and there are over 1 lakh downloads, as of March-end. In addition to new deals and discounts every day, and the convenience of easy returns and refunds, CityMall is also trying to engage end-users with other features within the app. “Horoscope is one of the top features that we have on our app,” Kikla says, because many people are interested in it. Such features also entice end-users to open the app every day, which sometimes translates into new orders.

Typical of most apps today, first-time users enter their mobile phone number, get a one-time-password for verification, and enter their location. In this reporter’s case, the app returned a message saying CityMall was currently not operating in the selected location, in Bengaluru. In the village of Tint, however, the app would have stored the address and gone on to show the home page with the day’s deals and offers. ‘Every day the right price,’ is CityMall’s motto. Much of this happens in Hindi, the language that the app currently uses by default, as CityMall is targeting Hindi-speaking regions first.

WhatsApp remains an important conduit between community leaders and their end-customers. The community leader often sends links to the day’s deals through WhatsApp. For end-customers who don’t have the CityMall app, the link takes them to Google’s Play store, from where they can download the app for end-customers who already have the app, the link leads to the app page showing the day’s offers. At the backend, CityMall uses WhatsApp’s business APIs (application program interfaces).

Growth path

“We were initially very grocery-focussed,” Kikla says. “With maturity, we are also seeing demand for FMCG [fast moving consumer goods] products, and in the last three to four months we have realised that the platform is much more horizontal than what we had envisioned it to be.”

The community leaders are now also selling shoes, T-shirts, cookers, electrical appliances and so on. “In fact, the fastest growing category for us right now is what we call general merchandise and long-tail categories. We also are finding good traction with feature phones.”

Buoyed by these trends, CityMall is also experimenting with new categories, including fruits and vegetables and even insurance, offering “the most commoditised ones”, such as two-wheeler insurance. Overall, the founders have been looking at building an alternative distribution channel in the form of community leaders. While the hook to building that channel are groceries, once that trust is established between the end-consumer and the community leader, other products can also be sold, they reckon.

The community leaders pay CityMall directly, and collect payments from individual end-customers. Cash is still king, but India’s government-backed unified payments interface (UPI) is also becoming popular. Experienced community leaders have even started giving credit to their end-customers out of their own pockets, Kikla says.

In addition to individuals and households such as Sunita Yadav’s, CityMall also enlists small local shops, like those that offer mobile phone top-ups or electrical repairs and so on. Through most of 2020, sales volume on CityMall has grown 35 percent month-on-month, on average, Kikla says, while declining to give specific numbers.

The venture raised $3 million in seed funding in June 2020, from early-stage venture capital (VC) firm Elevation Capital, WaterBridge Ventures and a few other investors. In March, it announced a series A investment of $11 million, led by Accel, also an early-stage VC firm, with Elevation Capital and others joining in. Kikla and Verdhan want to use the money to expand their operations to 20 to 25 smaller cities and towns. Eventually, they want to touch 400 cities.

They are also building their own logistics network, including warehouses and hubs. CityMall purchases products from a range of sellers—small local mills and farms, all the way to national brands. And because the established logistics providers don’t operate in the small towns that CityMall is focussing on, the startup is partnering with owners of trucks and small fleets of tempos and commercial vehicles in the unorganised transport sector.

“In a way, we have also decentralised the network,” Kikla says. This is because the last-mile delivery is the responsibility of the community leader. And since the community leader also doubles as a marketing and sales agent, CityMall’s costs on such activities are lower. This is also important because unlike a metro dweller placing a Rs 2,000-order on Big Basket, India’s biggest online groceries seller, Sunita Yadav’s customers would typically place orders of Rs 300 to Rs 500. Some customers, of course, buy an entire month’s supplies in one go.

For all these customers, “Price is greater than choice, which is greater than convenience,” says Akarsh Shrivastava, a vice president at Elevation Capital. So even if the CityMall model is able to create, say, a 5 to 10 percent price advantage over other options, including buying from the local grocery store, it will attract and retain customers.

Market opportunity

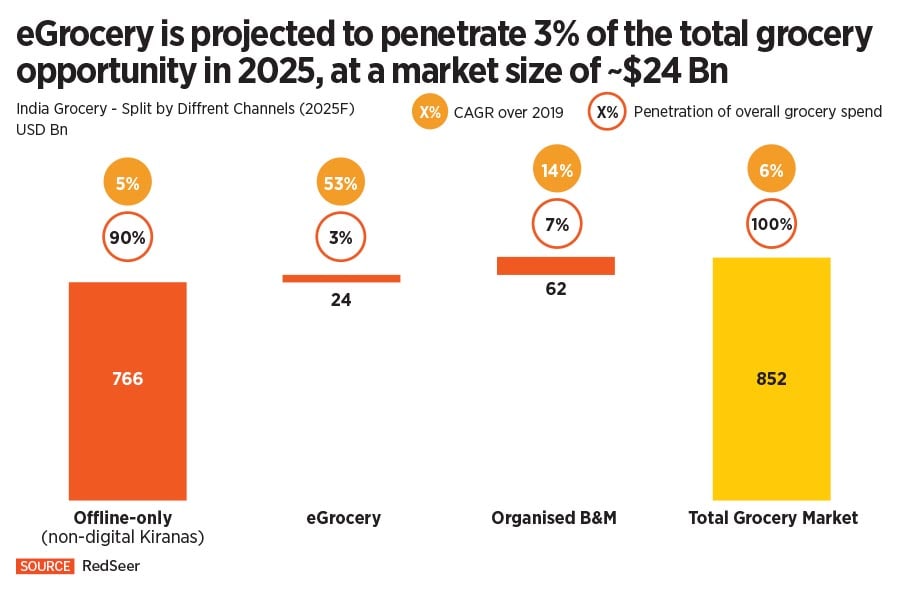

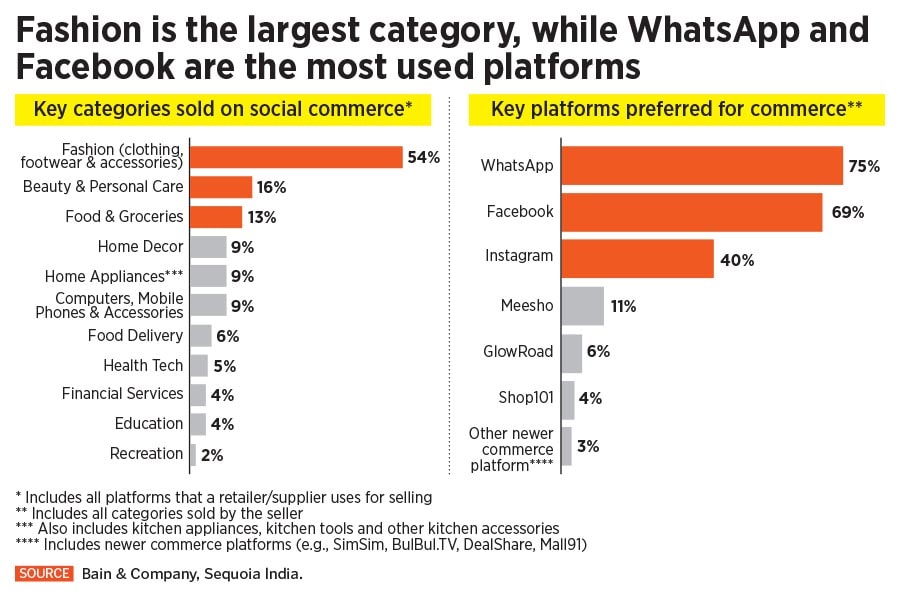

The market opportunity, per se, is very large. Groceries in India are a $600 billion market today, with almost all of it bought offline online sales account for 0.3 percent or so. Some industry estimates project the market size to hit a trillion dollars in five years. A better estimate to look at, perhaps, is the projection for social commerce. And here, grocery isn’t the leading category yet—fashion is, followed by beauty and personal care products, according to Bain & Company, a consultancy.

Overall, social commerce will grow tenfold from today’s levels to between $16 billion and $20 billion, by sales volume, in 2025, Bain estimated in a December 2020 report. From there it could go to between $60 billion and $70 billion by 2030, according to the report, written in collaboration with Sequoia Capital.

Another projection is that the e-groceries segment will grow to about $24 billion dollars by 2025, growing at 53 percent compounded annual growth rate from 2019 levels, according to another consultancy Redseer, in Bengaluru.

“Grocery isn’t a severe pain point per se, and people have solved their groceries wherever they are,” Shrivastava says. It is a business where price sensitivity is high and profit margins are low. In China, social commerce market leader Pinduoduo is succeeding with its ‘team purchase’ model because the critical mass of consumer density and frequency of purchases exists there. The US-listed company reported a monthly active user base of 720 million people for December.

India, despite the rapid increase in people with access to mobile internet in recent years, has only about 154 million households that actually made purchases online in 2020, Redseer estimates. And the long-term success of CityMall hinges on building this alternative channel to the point where a Sunita Yadav’s customer routinely turns to the CityMall app as a default behaviour. “That’s when they would have created a large business,” Shrivastava says.

It’s fairly early days for the young venture to be profitable. Sticking to only the current eight cities and going really deep in those few markets could get CityMall to profits in two years, but “the point is to build a very large business,” the venture capitalist says. That means going from city to city and at some point to multiple new cities simultaneously. That means spending a lot more money. Profits will have to wait.

Sunita Yadav, a school teacher, and CityMall ‘community leader’ in village Tint, in Haryana, on her way to deliver groceries in her neighborhood[br]

Rise of social selling

The bigger picture is that ventures like CityMall are getting small-town India to change its behaviour and go online for everyday needs, which represent a very large opportunity. People like Shrivastava are betting that in five years, there"ll be at least three or four more unicorns in the ecommerce sector in India. These unicorns will catalyse the creation of hundreds of thousands of micro-entrepreneurs, who will be like grocery stores in themselves—minus many of the inefficiencies of the current brick-and-mortar model. And since groceries is a high-frequency activity, it offers something akin to an annuity income.

And a new breed of social commerce startups is leading this change. Meesho is perhaps the largest, focussing on apparel, with millions of women on its network selling to their friends and neighbours. Meesho, in fact, is reported to have landed a $250-million investment from SoftBank Group, making it a unicorn in the process. Bengaluru’s GlowRoad is the next biggest platform, according to Bain, followed by Mumbai’s Shop101. Jaipur-based DealShare is another venture that started out by simply offering deals on WhatsApp. It has raised $21 million in its third major funding round.

Gurugram’s Bulbul uses video streaming to engage customers, with marketers—often called influencers in social media parlance—explaining the features of products. Other ventures trying to build social commerce-based businesses include Mall91, EkAnek and SimSim. Even ecommerce giants like Flipkart have started experimenting with social commerce. Last July, Flipkart announced it was offering continuous video feeds of influencers promoting various products under its 2GUD brand.

More than just ecommerceBack at CityMall, there are early signs of product-market fit, and business model and category fit as well, Shrivastava says. And once the trust is established between community leaders and their end-customers, it opens up the possibility of selling products in multiple categories. China’s Pinduoduo even sells iPhones today.

If companies like CityMall succeed, there may be a larger revolution in the works, more important than selling groceries online. “I’m college educated, but in Haryana, people don’t allow women to go out and work,” says Sunita Yadav over a phone call. “Staying at home, I offered tuition to some children, but eventually managed to join a small private school in the locality.” Today she teaches children from kindergarten all the way to Class 10. Her husband works at a petrol station some 25 km away.

“I realised that this app opens up the digital world to us and helps me build an identity for myself in my community. And I dream of bringing it to my entire village,” adds Yadav. She estimates there are a thousand households in her village.

She went from neighbour to neighbour and beyond, and convinced people to download the app on their smartphones and start placing orders with her. She has, on occasion, gone herself to a market in Rewari to purchase groceries for her customers. “Today they just pick up their phones and send their orders to me,” she says of her regular customers.

The money is one thing, but “CityMall has helped me create an identity for myself in my entire village… people know me,” she says. “Earlier, my constraints were such that I had to cover my head to just step out, but today, I get to speak with everyone with confidence. There is a sense of happiness inside me and in my family.”

Graphics by Sameer Pawar

First Published: Mar 30, 2021, 15:26

Subscribe Now