On the trail of how 10-minute delivery works—and doesn't

A bunch of local firms are vying for a piece of India's $620 billion grocery market with quick commerce. But the race is not just about time

8:00 AM: It’s time for breakfast and 25-year-old Himanshu Kumar pulls out his phone. He opens Zepto, a 10-minute instant grocery delivery app, to place an order for fruits and some frozen food. The order is confirmed, arriving in 10:00 minutes, and the countdown starts. A notification from the app pops up on Kumar’s mobile screen: ‘Sit back and relax while we deliver your order at lightning speed’.

8:01 AM: The nearest dark store, about three kilometers away, accepts Kumar’s order and swings into action.

Located in gritty and grim areas, these stores are not accessible to the public. The interior, much like a supermarket, has aisles of shelves stacked with everything from grocery items including fruits and vegetables, dairy products and instant food items to home utilities and even smoking accessories like rolling papers. The packers, constantly monitoring for new orders and quickly accepting a new order, get cracking as the countdown starts.

Meanwhile, some Zepto riders are waiting at the counter to pick up their orders, while some are waiting to receive a new order. A huge screen displays the details and status of active orders and a store manager overlooks and monitors all the activities from order fulfilment to available stock.

8:02 AM: The packer who is assigned Kumar’s order picks up the items on the list, packs them in a bag, rechecks the items against the list and prepares to hand it over to a Zepto rider.

8:03 AM: Zepto rider Hussain Khan (name changed) has been assigned to deliver Kumar’s order. Khan, who has been working with the company for over a month, arrives at the store to pick up his first order of the day. He lives two kilometres away from the dark store and till date has fulfilled approximately 600 doorstep deliveries. Thirty-seven-year-old Khan usually starts his day at eight in the morning and finishes by seven in the evening.

8:05 AM: Khan picks up the order and gets on his two-wheeler to deliver the order on time, in 10 minutes, as promised.

On the same page where the countdown of the order is ticking on Kumar’s phone, there is a small section ‘Know More’ which clarifies that: a) delivery partners ride safely at an average speed of 15kmph per delivery b) there are no penalties for late deliveries and no incentives for on-time deliveries c) delivery partners are not informed about the promised delivery time.

8:10 AM: Thankfully Kumar doesn’t live far away and Khan manages to deliver the order at the doorstep in 10 minutes. Khan says, “The best thing about working for Zepto is that I don’t have to travel long distances like I had to when I was working as a delivery partner for Zomato and Swiggy. I’m able to save time, energy and petrol. However, in the initial weeks I was getting more orders but nowadays the rush of orders has decreased because the company has onboarded more riders, which according to me are not needed as the orders are getting divided."

Khan earlier delivered 25 orders per day which has now come down to 14 orders. “I have been working for more hours to get more orders. I don’t really wish to leave Zepto but if this situation continues I might switch to Ola or Uber."

8:11 AM: Kumar’s breakfast is ready to be made. “A lot of times my breakfast and dinner are sorted by ordering from this app. I used to order from Zepto twice a day though this frequency has now come down to thrice a week due to odd work hours and other reasons," says Kumar, an inside sales manager at an edtech company.

He recalls another incident when some time ago their cook ran out of certain ingredients for the dish she planned to prepare. Kumar quickly ordered the required ingredient from Zepto, even as the cook kept other things ready. “When we didn’t have the privilege to order from these apps, we either used to borrow from neighbours or quickly rush to the nearby shop to get the items. Thankfully we don’t need to do that anymore and it’s available at the tap of a finger." Kumar adds that he has also been saving money as he avoids ordering from restaurants using food delivery apps like Zomato and Swiggy, meals that would easily cost him Rs 300-400. As an alternative he orders grocery items and instant food, which turns out cheaper for him.

Though in many instances the order doesn’t arrive in 10 minutes. After speaking to several Zepto users and riders, Forbes India found that the delivery time goes up to 20-25 minutes. “We’re in a position where we deliver faster than all our competitors. So we’re not particularly concerned about that. Our customer experience metrics are one of the best in consumer internet in India right now. As long as we’re delivering good experiences, we’re seeing solid retention scores. We’re very happy about how loyal the customer base is," says Aadit Palicha, co-founder and CEO of Zepto. The company claims that their average delivery time remains below 10 minutes across markets and that it receives over one million orders per week, and onboards one lakh new users daily.

Taking inspiration from Western companies like Instacart, Gopuff and Gorillas, which deliver daily essentials right to the door, a bunch of local firms are contending for a piece of India’s $620 billion grocery market by promising delivery times of just 10 minutes.

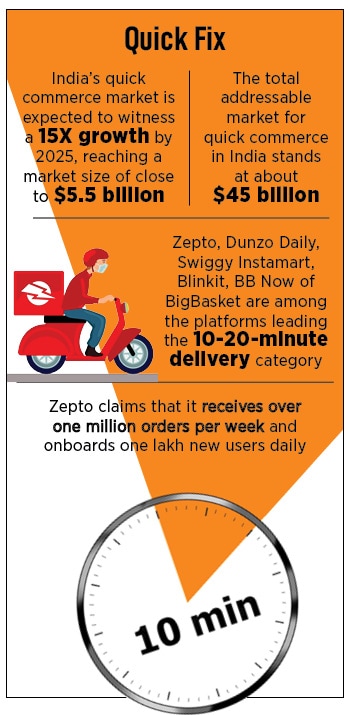

According to a 2022 RedSeer Consulting report, the total addressable market for quick commerce in India is $45 billion, driven by urban areas on the back of mid-high-income households. Currently, players like Zepto, Dunzo Daily, Swiggy Instamart, BB Now (BigBasket’s quick delivery offering) and Blinkit (formerly Grofers) are dominating the space, offering anything between 10-minute to 30-minute delivery times. The report adds that India’s quick commerce market is set to touch $5.5 billion by 2025—15 times its current size.

But will these instant grocery delivery apps be able to take over kiranas’ dominant share of top-up purchases that customers make in between bigger bulk shopping trips? It looks like there’s still a long way to go. According to the RedSeer report, kiranas account for more than 95 percent of India’s grocery market. Supermarkets still account for only about 4 percent, even though they first appeared 30 years ago, and online groceries haven’t cracked 1 percent in a decade. Besides, roughly two-thirds of India’s 1.3 billion people live in rural areas largely untouched by these more modern forms of retail.

However, India’s quick commerce is exploding with more players entering the fray and investors pouring in money in this category. The quick commerce model requires a significant amount of investment and tech boost and India’s tech startups are drawing huge interest from foreign investors who are keen to cash in on the growing use of digital payments, internet and smartphones in the South Asian market. Recently Zepto, founded in April 2021 by two 19-year-old Stanford dropouts, raised $200 million in fresh funding that values the company at around $900 million. The funding round was led by existing investor Y Combinator, a prominent Silicon Valley fund. The 10-minute race was set in motion when Mumbai-based startup Zepto secured $100 million in funding in December last year. SoftBank-backed Blinkit, which recently got acquired by Zomato, followed suit and initially promised to deliver groceries in 10 minutes though it later stopped saying the same. Other rivals including Dunzo, backed by Indian billionaire Mukesh Ambani"s Reliance and SoftBank-backed Swiggy are all betting on fast deliveries in the burgeoning quick commerce sector.

There are some that dropped out of the race. Ola Dash, the grocery delivery service launched by mobility unicorn Ola, recently scaled down its business and temporarily suspended operations of most of its dark stores due to a shortfall in demand. Ola got on to the bandwagon in December 2021, starting with Bengaluru and offering basic groceries. The company had plans to launch a network of 500 dark stores in 20 cities. Similarly Blinkit also struggled to cope and raise funds which led to laying off of employees and shutting down warehouses in March this year, which recently led to its acquisition by Zomato.

Till 2020, the share of digital commerce in the Indian economy was on a steady growth path, but with the advent of Covid-19, the pace got massively accelerated. Everything from payments to meetings to grocery shopping moved online much faster. Quick commerce is just the next iteration of the same, explains Kabeer Biswas, CEO and co-founder of Dunzo. “Globally we see highly verticalised players focused on building this category. A higher spending power amongst the middle and higher-income groups, and their need to have easily accessible choices and convenience at their doorstep is one of the key drivers for quick commerce growth. Time is valuable and if mundane activities can be fulfilled at the click of a button with a nominal fee then that’s an option that is only seeing increasing adoption," he adds.

Dunzo pioneered hyperlocal quick commerce in India in 2016. They enabled consumers to courier items from point A to point B in a city, to procure anything they wanted from any shop in the city, and eventually also enabled discovery for both local merchants and consumers through the Dunzo app. Later on, after realising the absence of quick fulfillment for daily essentials, as well as the fact that the frequency of purchase is much higher for online grocery shopping versus other forms of e-commerce, the company launched Dunzo Daily in July 2021. “From launching Dunzo Daily only in Bangalore in the middle of 2021, we have gone on to cover eight top cities in India in a span of six months. We have over 125 mini-warehouses across eight cities in India," says Biswas.

The trend of q-commerce has caught on because of sheer consumer convenience, even though cost of operations is much higher and discounts are lower on instant services. The market has a lot of potential but experts suggest it will be the survival of the fittest. Most q-commerce companies at present are focussed on groceries, which is traditionally a low margin business. In the longer run, divergence into other segments like medicines, beauty products and even basic electronic accessories to expand the SKU base will be important to survive in the market. Quick commerce is also very location-dependent. Breaking unit economics might be possible in some places and extremely challenging in others. It’s about picking the right locations with a high order density.

Fourteen-year-old Saumay Mahajan is an avid user of Zepto. When he first saw an advertisement for the app on YouTube, he was amused by the idea of having groceries delivered in such a short time. Today he orders from the app at least nine times a week. From ordering dairy products for the household to satisfying his cravings for chips, the class nine student has become a loyal customer of the app. “The orders don’t always reach in 10 minutes, it goes up to 15 minutes most of the times. But I’m okay with it as long as I’m getting whatever I want to eat so quickly," he says.

Similarly, 27-year-old Abhishek Sarkar heavily relies on q-commerce for his daily grocery needs as he would rather avoid the long queues at the supermarket. Sarkar mostly uses Zepto, followed by Blinkit and Dunzo Daily. He averages two orders a day, with the highest being four times a day. “These apps have saved us many times when we had guests over and we had run out of snacks. I instantly ordered snacks and received them at the doorstep without worrying about rushing to the nearby store. However, I have noticed that the deliveries were faster initially, now they have slowed down a bit and take longer than usual."

A couple of decades ago, getting things delivered within about an hour of placing an order seemed like a far-fetched idea. Today we get something as small as a matchbox delivered in 15 minutes. Consumers thrive on instant gratification, and once the addictive drug is administered, there’s no escaping the addiction. As online shopping and same-day shipping have now become a part of life, research suggests rapid commerce will significantly transform customer buying behaviour and the grocery retail chain by delivering speedier alternatives and a more comfort-driven buying experience.

Indian customers, points out R Raman, director of Symbiosis Institute of Business Management, are always in a hurry and in a rush to get things done. Check the number of people rushing and crossing the signal when it is just turning from orange to red. Or the number of people trying to get up and out of the aircraft when an aircraft lands. Knowingly or unknowingly the Indian middle class and the upper middle class are in a rush and that has been ingrained in the DNA, he explains. “Hence when an organisation is satisfying the rushing need by delivering groceries quickly it is bound to be a successful model. The data also shows the same. The sharp growth indicates that customers are accepting it and there is a clear need for quick delivery. In my view the positive aspects in the model like the number of jobs created, the growth in economic activity, taxes collected, and also the convenience that this quick commerce gives must be appreciated and should not be ridiculed."

While the demand for quick commerce is rising, it also raises road safety concerns for delivery bikers considering India has one of the world"s most accident-prone roads. These companies are selling the fantasy of instant delivery among customers. But at the same time these platforms wash their hands off the dangers by concealing the way they structure the work to portray as if delivery workers independently engage in traffic violations and hazardous driving conditions risking themselves and other pedestrians on the road, explains Shaik Salauddin, National General Secretary of Indian Federation of App-based Transport Workers (IFAT).

“It is incentive-driven work conditions that these platforms actively shape which incites the delivery workers to chase those incentives targets and motivate delivery workers to resort to such acts," he says. He adds that many of their delivery workers work for over 10 hours and the platform actively engages such work practices by not setting any cap on the maximum hours a delivery worker can log in. “Prolonged working hours on the road add to the risk of being prone to accidents," he points out.

Palicha of Zepto affirms that the company does not put any pressure on the riders to deliver the order in 10 minutes and does not charge any penalties if the order is not delivered in the promised time. The actual time and speed of the rider is displayed in real time only for the customers. “Faster deliveries are about short distances and not fast speed. Apart from this, from providing a good shelter while the rider waits to get the next order and access to clean washrooms to basic insurance, we provide all the required benefits to our delivery partners," he says.

Biswas of Dunzo too assures that both partner safety and delivering good quality products are of utmost priority to the company. “Our USP doesn’t bank on the promise of delivery within a stipulated time frame nor do we market our brand that way. Our brand promise is to deliver good quality and fresh products at the best price within the shortest time possible. As a local commerce platform, our consumers value the quality, selection and convenience we offer. We do not encourage the practice of favouring speed above all else."

All said and done, quick commerce is here to stay in India. There will mergers and acquisitions in this space and the rule of three will be a reality in a few years from now, concludes Raman.

First Published: Jul 01, 2022, 14:52

Subscribe Now