Art of the allegory in literature

Telling a tale through hidden meanings

Hear the term ‘fantasy writing’ and the images that leap to your mind are likely to be from the Tolkien universe—The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, the mythological back-stories collected as The Silmarillion—or from CS Lewis’s Narnia, or one of the countless series inspired by them. These are fictional settings that have been created from the ground up. Even when the things that happen in the story comment on aspects of our own world (as is notably the case in Terry Pratchett’s Discworld books and Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials), the reader knows that the place itself is invented.

But fantasy is a broad word. Another, subtler form is that of the allegorical narrative which is located in a mostly familiar setting but has things happening in it that don’t fit the straitjacket of ‘realism’. George Orwell’s Animal Farm is an iconic example: In reality (as far as we know), pigs don’t use human speech or organise themselves into dictatorships yet this novella is set in our world, and most people with knowledge of Orwell’s life and the political events of his time would recognise it as an allegory about the Russian Revolution.

Such writing sometimes takes the form of speculative fiction set in a future (or alternative) world—as was recently done by Shovon Chowdhury in the splendidly imaginative The Competent Authority, set in the 2030s. The India of this dystopian novel, having been comprehensively nuked by China, is run by a mad bureaucrat, and the only hope for the future may lie in going back to the past—a group of people with special time-travelling powers set off to see what can be done to alter history. Weird and ‘fantastic’ as all this may sound, there are instantly identifiable figures here, such as an unnamed prime minister who comes from a long political dynasty (she is the granddaughter of a much-feared woman PM of the 1970s, if that helps) and a crude, bullying policeman.

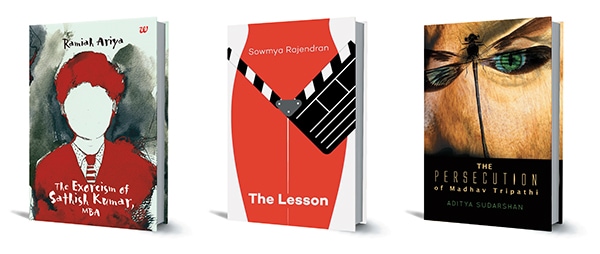

A slimmer, less ambitious but often-potent satire is Sowmya Rajendran’s The Lesson, which takes the unsavoury facts of gender discrimination in real-world India and only mildly exaggerates them to create a picture of a society where state-sanctioned rapists coolly make phone appointments with their next victims—the women who are “asking for it”—and Dupatta-Regulators ensure prescribed standards of morality (while having fevered nightmares about an anarchic world where everyone roams around naked). The icy detachment of Rajendran’s writing is sometimes very effective—as in a scene where a woman who is to be raped on a live TV reality show is briefed about the “hot” actress who will play her in the buildup episodes—though I did feel that a little more could have been done with the premise, and the satire could have been more cutting.

“He feels empty. Hollow. Unreal. He feels he has no business being alive.” These words could describe some of the people in Rajendran’s book, but they are the opening lines of Altaf Tyrewala’s long story ‘MmYum’s,’ included in the collection Engglishhh: Fictional Dispatches from a Hyperreal Nation. And they refer not to a flesh-and-blood person but to a mascot clown named Arnold, made of plastic and sitting on a bench outside a chain store. Fed up of being someone else’s puppet, he decides to get up and wander the streets.

The misadventures that follow comment on the workings of capitalism and those who become slaves to it—including conscientious objectors who end up being fence-sitters because they can’t resist an occasional dose of junk food and gassy cola—but they also comment slyly on this type of narrative. “You must be dumbfounded to see me,” Arnold tells a writer named Unnati in one scene. She shrugs her shoulders. “It’s an allegory, all sorts of things can happen in allegories. I don’t mind playing along.” As she knows, one of the characteristics of this form is that it spells ideas out for the reader—in an often simplified, pared down way—while simultaneously making inside jokes and self-referencing. If lazily done, this can become tedious very fast.Tedious is not a word I would ever use to describe Ramiah Ariya’s funny, fast-paced novel The Exorcism of Sathish Kumar, MBA. While Tyrewala’s Arnold is, almost literally, tied down to his job (in fact, the poor mascot clown that replaces him has screws driven through his hands and feet to keep him from bolting), the protagonist of Ariya’s book isn’t much better off: As the narrative opens, Arjun is summoned by the upper echelons of management in his tech company and deputed to the mysterious “EXM” team, with a very strange list of tasks to perform—procuring gaanja, for example. The depiction of the corporate world here may remind you of the more surreal Dilbert strips, such as the ones where the geeky engineer is sent to the dreaded accounts department and meets trolls who feed him unicorn horns. This novel becomes increasingly weird and fable-like as it goes along, culminating in encounters with a sorcerer who communes with the dead, a strange otherworld named Ahi, and the revelation that the true meaning of life is shareholder profit (something that most corporate slaves learn over time without ever having to go to strange otherworlds!).

Franz Kafka was one of the major practitioners of a different sort of fable—the claustrophobic, nightmarish type—and Kafkaesque was the word that leapt to mind as I read Aditya Sudarshan’s intense The Persecution of Madhav Tripathi. (An early chapter is titled ‘The Castle’, as if in tribute to the master of paranoia’s famous story about alienation.) Sudarshan’s novel is about a privileged man who at first seems to have the future nicely laid out before him—but after losing his bearings (literally and otherwise) while coasting down a city road, Madhav Tripathi finds himself caught in an escalating series of strange events. This story about liberals—or people who think they are liberal and sophisticated—being beset by the forces of darkness, and exposed to their own pretentiousness in the process, may be too dense for some tastes. But it is full of arresting imagery, such as an early scene, a party set at a wildlife sanctuary, where guests float about like butterflies (or perhaps like the dragonfly pictured on the book’s cover, which also makes an appearance later in the narrative). ‘Civilization’ meets the cave in these passages, as it does in most of the other books mentioned here—and by the time you finish reading them you may no longer be sure which is which.

(The author is a Delhi-based writer and journalist)

First Published: Jul 28, 2015, 06:17

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Jul 16, 2010 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)