Combating cancer with big data

While still in their 20s, Nat Turner and Zach Weinberg built a $2 billion company to pursue an impossible dream—to conquer the Big C. They've not only made fast progress—they've also gotten rich tryin

Zach Weinberg (left) and Nat Turner on the roof of their new offices on Spring Street in Manhattan. Flatiron Health is the third company they’ve started together

Image: Matt Furman for Forbes

In 2008, when he was 23, Nat Turner was on a hike in North Carolina with his six-year-old cousin, Brennan Simkins. Brennan’s legs got weak, and the weakness kept getting worse. He turned out to have a rare and deadly paediatric leukemia that kept coming back after treatment. When Brennan needed a second bone marrow transplant, several hospitals refused to do it and his family was losing hope—until they found a specialist who would help. Exasperated, Brennan’s father asked Turner: Why doesn’t one hospital know what others will do? Is there anyone collecting statistics?

“All right,” Turner remembers thinking, “there’s a lot of value for patients locked in the clinical data. We should be the ones who unlock it.”

For another recent college graduate, that might have been merely a fleeting “deep thought”. But Turner, along with his college friend and business partner, Zach Weinberg, was looking to start a third company. His first, an online food delivery business Weinberg and he started their freshman year at Wharton, had failed, but a second one, an online advertising business called Invite Media, sold to Google for $81 million in 2010, when they were 24.

Free from financial concerns and still working at Google, they were filling their office whiteboard with ideas about what to do next. They were fascinated by health care. “We were very titillated by it because it’s so complicated and neither one of us knew anything about it,” Turner says. Brennan’s experience became a beacon guiding them on a new effort.

Turner and Weinberg’s new company, Flatiron Health, was founded in 2012 with the goal of pooling patient data from electronic health records in a way that could answer scientific questions and improve medicine. It raised $328 million, and as a result Turner (the CEO) and Weinberg (the COO) headlined the 2015 Forbes 30 Under 30 Healthcare list. Forbes estimates Flatiron’s annual revenue approaches $200 million. In April, Roche, the Swiss pharmaceutical giant, bought Flatiron for $1.9 billion, not including the $200 million stake it already owned in the data science company. The deal made Turner and Weinberg $250 million each, Forbes estimates.

Flatiron aims to overcome one of the biggest limitations on medical research. If researchers want to know whether a new medicine is effective, there is really only one option: Recruit patients to volunteer for a clinical trial and randomly assign them to receive either the new medicine or a placebo. But this approach has shortcomings. Sometimes it’s not ethical to make patients take a placebo. And clinical trials involve carefully selected patients. There is always the worry that results will be different in the real world.

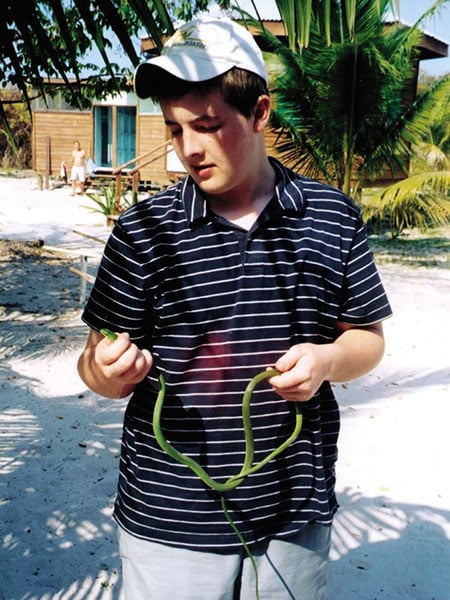

But getting data from the real world is extremely difficult. At many cancer hospitals, administrators may not even know basics like how many patients have breast or pancreatic cancer. Flatiron’s solution is to own the right to use data from an electronic medical record used by nearly 280 medical practices for 2 million patients. It pays 1,000 contractors to read the text notes doctors write about their patients and turn the notes into data on what medicines patients take, how well they work, and what happens next. This can be turned into a larger data set that measures how well medicines are actually working, a potential that has Flatiron collaborating with all the largest makers of cancer drugs. Snake charmer: Nat Turner bred snakes as a pre-teen and turned his love of reptiles into a business in high school “I believe that the public wants to know how patients with cancer do,” says Thomas Lynch, the head of research and development at Bristol-Myers Squibb, who has been a Flatiron booster for years. “Real-world evidence is so important to understanding how to treat patients better and how to allocate resources.”

Snake charmer: Nat Turner bred snakes as a pre-teen and turned his love of reptiles into a business in high school “I believe that the public wants to know how patients with cancer do,” says Thomas Lynch, the head of research and development at Bristol-Myers Squibb, who has been a Flatiron booster for years. “Real-world evidence is so important to understanding how to treat patients better and how to allocate resources.”

It sounds great, but there are ethical pitfalls. Having contractors peer into patients’ medical records, even with most identifying information removed, can seem creepy at best and an invasion of privacy at worst. And some scientists still have doubts about how useful the resulting data are. Can you really tell how good a new medicine is from Flatiron’s data? Even Nat and Zach admit that the jury is still out.

For Turner, it all started with snakes. Because his father was a geophysicist for the oil company Conoco, he moved around a lot as a kid, living in Louisiana, The Netherlands and Scotland. In Louisiana, his childhood fascination with dinosaurs led him into the neighbourhood swamp to hunt reptiles. “It was so easy!” he says. “It was in our backyard.”

Most kids would just keep a few creepy-crawlies in a tank. Turner started breeding them for profit. “One of my snakes had babies, and I sold the babies to a pet store for, like, $100,” Turner says. “As a nine-year-old, that’s pretty cool.” He discovered there were websites through which he could sell reptiles at a bigger scale. He kept the business up even after his family moved to Houston when he was in middle school. By the time he was in high school, he was working with a friend who kept hundreds of reptiles in a trailer. But he didn’t stop at snakes. He created a website to advertise baseball cards he was selling on Ebay, as well as websites for other reptile fans and then for other businesses.

When Turner arrived at Wharton in 2004, his web design business was in full swing. Wharton had a programme—intended for upperclassmen—that allowed undergrads to meet with entrepreneurs. Turner was so eager to meet with Josh Kopelman, a venture capitalist at First Round Capital who had founded his first successful company while an undergrad at Wharton, that he built an automated program to spam the web-signup system so he could set an appointment. Turner brought a business idea to pitch, but instead they wound up talking about fixing First Round’s website. Kopelman was blown away. “The level of curiosity, the level of maturity in his thinking, just every bone in his body screams entrepreneur,” Kopelman remembers. At 7 pm, on his way home, he offered Turner, still a freshman, an internship at First Round.

[qt]It’s stunning how far behind banking and manufacturing medicine is.”[/qt]

Turner made an even more consequential connection in a class he was taking only because it sounded easy. Wharton required students to take a course in writing. One that jumped out at Turner involved writing about blockbuster films. While eating catered dinners, students would watch movies and then write short essays about them. For one assignment, they were supposed to pair up with someone else. Turner was too shy to approach anyone. But another freshman in the class was going from person to person, asking, “Want to watch Elf?” referring to the Will Ferrell/Zooey Deschanel Christmas comedy. “I like Elf,” Turner replied. He and Weinberg became fast friends.

They quickly discovered that both had been dreaming of building something from scratch. Weinberg didn’t quite have Turner’s entrepreneurial chops at New York’s ultra-competitive Hunter College High School, he’d had to focus on schoolwork full-time to keep up. But he found time to spend a summer playing online poker and loved what he refers to as “the high school hustle”: Throwing parties and charging a cover at the door. His friend and he had an idea that Turner liked: A company they’d call EatNow, which would allow college students to order food delivery over the web. “Growing up in New York City, one of the things you get really used to is delivery food,” Weinberg says. Turner adds: “Campus food sucked.”

That summer, while Turner interned at First Round (which, by the way, declined to invest in EatNow), Weinberg and another friend were driving from Philly to Boston to New York to New Haven, trying to sign up restaurants. It was harder than they’d thought they were sending restaurants faxes with orders on them. They also made the mistake of taking their cut from the restaurant, not from the customer at the point of sale some restaurants just didn’t pay them. At the end of their sophomore year, they sold the business in a fire sale. The assets are now part of Grubhub.

But their partnership was cemented. “One of their strengths is the speed with which they learn and willingness to appear stupid when they start,” Kopelman says. They are two guys willing to tell each other, “That’s the dumbest idea I ever heard.” Their next idea came as they watched basketball and saw small ads popping up in front of the game. Initially, Kopelman told them it was an idea he was in no way ready to fund. But they went into a meeting with Andrew Boszhardt, a fund manager who had just made a big profit by funding StubHub. After just a few minutes, Boszhardt asked how much money they needed. The two had not even discussed it between themselves. “$250,000,” Turner blurted out. “Okay,” Boszhardt said.

Invite Media would pivot at least eight times. At first they thought they’d build a company that helped other people build ads. But Weinberg says they spent hours and hours with Brian O’Kelley, the chief executive of the ad network AppNexus, who explained to them that advertising was moving toward an automated process. It was their first experience parachuting into a complicated business and figuring out how to create a product in it. And it worked: Invite allowed advertisers to buy ads across multiple networks. First Round eventually did invest. “It was really a bet for us on Nat and Zach,” Kopelman says. Invite raised a total of $4 million and was sold to Google in 2010 for $81 million. As soon as they moved into the Google offices, Turner and Weinberg started thinking about what they were going to do next. One thing was certain: It wasn’t going to be in ad tech.

Seeing Google’s well-oiled ad-tech machine highlighted “all the things that we did wrong [at Invite] that we definitely don’t want to do again”, Weinberg says. It also gave them time to think, because the integration was so smooth that they were soon “irrelevant”. They didn’t want to go back into ad tech, partly because they figured Google had it locked up and partly because they wanted to do something more meaningful.

Turner says Google asked them to stick around before starting another company, offering to shorten their stay from three years to two and allow them to work on other projects so long as they gave Google Ventures a chance to fund their new ideas. They filled a whiteboard in Google’s Chelsea offices with ideas for their next venture. Health care—and particularly cancer care—kept floating to the top. Part of the reason was that it was an area where they thought technology could make a difference. Part of the reason was Turner’s experience with his cousin. And it just kept coming up. One of the Google executives on the other side of the table during the Invite Media sale had a daughter with leukemia. (She’s now in remission the executive, Jason Harinstein, recently became Flatiron’s chief financial officer.)

Krishna Yeshwant, a partner at Google Ventures, says he met Turner and Weinberg because the search giant always wants to give a second look to entrepreneurs who were smart enough to sell their companies to Google the first time. He became one of their tour guides in the world of health. The pair had learnt in ad tech to listen to the ideas of people who were really experts, and their two years at Google turned into a listening tour. “When Google Ventures makes an intro to someone, usually that person is taking the meeting,” Weinberg says. At first they planned to create a non-profit that would help patients get second opinions, inspired by Turner’s cousin’s journey. But there was a problem with the non-profit idea. “Great engineers don’t work at non-profits,” Turner says. “They tend to go to places like Facebook.” And the more they talked to doctors, the more they worried that the idea wouldn’t scale.

Instead, they became infatuated with the data behind those doctor-patient interactions. Yeshwant introduced Turner and Weinberg to a company he was backing, Foundation Medicine, a biotech in Cambridge, Massachusetts, that sought to help cancer patients by sequencing their DNA. But Foundation told them it was having trouble following patients to find out how they did, because the medical system did not keep track of them. Turner also remembers a meeting with David Altshuler, then a genetics researcher at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and now the chief scientific officer at Vertex Pharmaceuticals, a big-cap biotech. Altshuler told him not to focus too much on genetics research, known as genomics. “I remember he said Foundation Medicine and all these companies are doing genomics, but no one’s aggregating clinical data,” Turner says.

Turner and Weinberg started Flatiron Health in June 2012, two years after they joined Google, and in January 2013 they raised $8 million from Google Ventures, First Round Capital and individual investors such as 23andMe’s Anne Wojcicki, plus some of their own cash. The idea was to create software that would run on top of electronic medical records to give hospitals an idea about how their business was working. Things went so well that within a year Nat and Zach were negotiating the sale of their company not to Roche but to Foundation. But the deal didn’t go through, because Flatiron saw even bigger opportunities. The two companies would eventually end up together, though. In June, Roche, the same drug giant that had acquired Flatiron, purchased Foundation in a deal that valued it at $5.3 billion.

From the beginning, the idea behind Flatiron Health was that it would pair a software business, which it would sell to hospitals, with another business that would get information from that software for another effort: To pool the data to power medical research. This is analogous to the 23andMe business model: Consumers pay for their genetic test data, but then the data are used to do research, which includes sharing the data with pharmaceutical companies. Turner and Weinberg say they knew from the start that drug companies would become important customers.

What was difficult was getting their nascent product—basically a glorified dashboard—into medical centres. Their first deal, with the University of Pennsylvania, dragged on for more than a year, mired in university bureaucracy. The first major cancer centre to adopt their early product was Yale. When asked why it happened, Weinberg gives a two-word answer: “Tom Lynch.” Lynch, the head of R&D at Bristol-Myers, was then the physician-in-chief of Yale’s Smilow Cancer Hospital. He remembers being introduced to Nat and Zach by other doctors he’d known since his medical residency. He was blown away by their ideas.

“It’s stunning how far behind banking and financial transactions and manufacturing medicine is,” Lynch says. “Seven years ago, I couldn’t tell you how many patients at Yale were being treated for pancreas cancer, real time. I could tell you when the information was filed with the state or when it was filed years later with the National Cancer Institute. But the ability to tell in real time how many patients had a certain disease or, more important, how were we treating them? How were they doing? Were we offering clinical trials that met the needs that the patients had? When a company like Bristol-Myers or Roche would come to me at Yale and say, ‘We have a clinical trial on a certain disease. How many patients do you think you guys might have that could be eligible?’ I didn’t have that kind of information.”

Flatiron did better at signing up cancer hospitals and doctors’ offices that were not linked with universities, accumulating about 20 by 2014. But when Weinberg and Turner met with drug companies, they still found that the data they had were insufficient. Turner remembers a meeting with Roche’s US unit, Genentech, as one of the low points at Flatiron. Zach and he went to meet with researchers there and were told that their technology and data processing were “awesome”, but that they just did not have data from enough patients in their system to be useful.

That led to an even bolder gambit: Buying an electronic-medical-records company. Most of the health-records business is locked up by giants like Epic Systems of Verona, Wisconsin, and Cerner of North Kansas City, Missouri. But cancer doctors used four smaller specialty products, and three of them were owned by companies for which health records were a side business: Varian Medical Systems and Elekta Medical Systems, which focus on building machines for zapping cancer patients with radiation, and McKesson, the medical-products distributor. The fourth, Altos Solutions, based in Los Altos, California, was solely in the electronic-medical-records business. Weinberg remembers having the idea of buying it with Nat in the car in Palo Alto, California. What would it cost? they wondered. Maybe $80 million? “Nat said, ‘Let’s go see if Google Ventures is willing to write the cheque’,” Weinberg says, “and I remember saying, ‘We should ask them, but there’s no way in hell they’re going to do it’.”

That was Google Ventures’ reaction, too. Yeshwant, the partner Turner called, had just put his infant daughter to bed in his new house in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “I think at that time I might have actually laughed,” he says. Turner responded: “I know you think I’m kidding, but I’m not. We’re going to do this.” In parallel, Turner and Weinberg convinced Altos to sell, saying they would make their electronic medical records even better, and persuaded Google Ventures to lead a $130 million financing round, of which $100 million went to buying Altos. The deal closed in May 2014. In a year, Flatiron went from having 17 employees, all in New York, to 135, in more than a dozen states. But it also meant that the company had added electronic medical records from thousands of patients to its database.

As they were closing the Altos acquisition, Turner and Weinberg were negotiating a hire that would transform their data business. Amy Abernethy had been trying to get real-world evidence about cancer out of electronic medical records for more than a decade. She ran a programme to do so at Duke University, which is one of the top hubs for conducting clinical trials in the US, and chaired a similar effort for the American Society of Clinical Oncology. The now-50-year-old oncologist instantly saw the potential in the data Flatiron had presented but declined an offer to be its chief medical officer. Nat and Zach roped her into helping them interview potential job candidates. One of them said to her, “If this job is so great, why don’t you take it?” Finally, in 2014, she did.

Flatiron has made great progress in finding uses for its data. Turner remembers that one of the high points of his time at Flatiron was when one of Abernethy’s researchers took Flatiron’s data and replicated exactly the results of a clinical trial. Flatiron says it has been able to replicate what happened in the control arms of existing studies with its own patient population more than a dozen times. Flatiron has even worked directly with the Food & Drug Administration.

In one study, FDA and Flatiron researchers found that patients with lung cancer who were treated with the cancer drugs Opdivo and Keytruda were older and more likely to smoke than the patients those medicines had been tested on in clinical trials. Another Flatiron study, not done with the FDA, failed to show that sequencing cancer patients’ DNA extended their lives (as parent company Roche believes should typically happen). The reason? The patients simply didn’t get drugs targeted to their cancer.

But not everyone is satisfied with the company’s direction. Ezekiel Emanuel, a University of Pennsylvania bioethicist who helped craft the Affordable Care Act, was one of the doctors who introduced Flatiron to Tom Lynch, the company’s big customer at Yale. While he still admires what Turner and Weinberg have tried to do, Emanuel doesn’t think they have succeeded in creating a system that uses data to improve care for patients. The worry is that instead of helping hospitals get better, Flatiron has basically become a data collection service for the pharmaceutical industry. “They didn’t crack that nut,” Emanuel says. “They still don’t have a company helping all those oncology groups to be much more efficient and consistently higher quality. I had hoped they would do more of it, [but] they never went that way.” And not every customer is happy. Barbara L McAneny, the chief executive of New Mexico Cancer Center, wanted Flatiron to help her centre move toward being paid for medical care only if patients do well. “They won’t let me have all the data I need to move into value-based care, even though it was promised,” she says. She also says the Flatiron product is “very good” for day-to-day use. Harlan Krumholz, director of the Center for Outcomes Research & Evaluation at Yale-New Haven Hospital, has another worry: “I think the question is: What about the next company who gains access to the data and is not responsible?”

Certainly, it’s possible to find patients who feel they should be getting a cut of any money Flatiron makes. “We’re tired of having pharma and payers and all kinds of other ancillary third parties mincing, toying and making money out of our data without us getting cut in,” says Casey Quinlan, a breast cancer survivor and patient activist. (Counterpoint: “I don’t have the luxury to be concerned about privacy,” says Ken Deutsch, a bladder cancer survivor. He wants more research now and would be fine with Flatiron using his data.)

It may all be a moot point. Flatiron does allow patients the opportunity to opt out of research and says its practices comply with the Health Insurance Portability & Accountability Act of 1996. And the Roche deal has cemented its business model in place. Roche wants to use Flatiron to create a new ecosystem for testing cancer medicines that will help the company and rivals like Bristol-Myers, which is one of Flatiron’s biggest customers.

The Roche deal started with an offhand comment Turner made to Daniel O’Day, 54, the head of Roche’s drug business, a Flatiron board member and one of Turner’s many mentors. At “a random restaurant” on New York’s Columbus Circle, Turner says, he mentioned “in a joking way” that he wouldn’t be opposed to selling. At Flatiron’s next board meeting last October, O’Day took Nat and Zach out to lunch at the Clocktower, a chic, sceney $30-a-plate pub directly across Madison Square Park from Flatiron’s old offices on 23rd Street. Turner and Weinberg had the cheeseburger. O’Day, a triathlete who avoids gluten, had the fish. “I should have had the burger without the bun,” he says. The discussion was not about financial terms but about the power of Roche’s balance sheet to allow Flatiron to move faster—Turner and Weinberg think they could fulfil their five-year plan in three years with Roche’s money—and about keeping Nat and Zach in complete control even after the sale. “I’m comfortable,” O’Day said. “But the question is: Are you, Nat, are you, Zach, comfortable?” They were. And now Flatiron is backed by the cash, expertise and interests of the world’s largest maker of cancer drugs. And, like it or not, that’s how cancer research gets done in America.

First Published: Feb 11, 2019, 17:44

Subscribe Now