The paradox that is Indian aviation

While the sector has been dealing with issues like loss-making airlines and poor regional connectivity, India remains the world's fastest growing aviation market

GMR group-run New Delhi airport handled 65.69 million passengers in fiscal 2018

GMR group-run New Delhi airport handled 65.69 million passengers in fiscal 2018Image: Shutterstock

India’s aviation sector is something of a paradox. On one hand, Asia’s third-largest economy continues to be the fastest growing aviation market in the world, with domestic passenger numbers clocking 18 percent growth in 2018. On the other, there is the perennially loss-making nature of airline companies, the colossal failure of a regional connectivity scheme and even massive debts raked by airport operators.

Yet, something about Indian aviation continues to lure many to enter the sector. In early March, Adani group, the country’s largest port developer, emerged as the winner to develop five operational airports that are now being privatised, in an attempt to improve their infrastructure. This is the first time that the salt-to-port operator has forayed into the airport space in India.

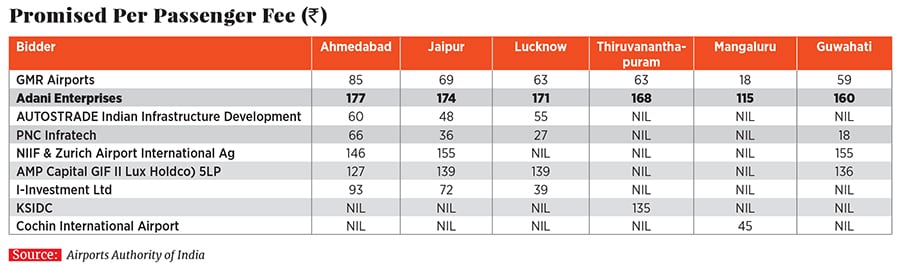

The Gautam Adani-led group now has the right to upgrade and operate the airports of Lucknow, Jaipur, Thiruvananthapuram, Mangaluru and Ahmedabad after it offered higher payment for per passenger fee to the Airports Authority of India (AAI). The group will get to manage these airports for 50 years. It makes it the largest private player in the airports business by the number of airports.

“The sector is a lucrative business to be in,” says Mahantesh Sabarad, head, retail research, at SBI Cap Securities. “Air travel in the country continues to grow and the airport side will see sustained growth. As far as the debt aggregated by other airport operators is concerned, it could be a case of miscalculation because by itself, the airport business has huge potential. This time, however, there has been a change in policy, and a better framework created for bidders made it easier and more lucrative.”

Earlier, when India decided to allow privatisation across airports, airport operators had to share a certain percentage of revenue with AAI. Over a decade ago, the GMR group agreed to share 45.99 percent of revenue with AAI for developing the Delhi airport while GVK group offered 38.7 percent for the Mumbai airport development. This time, however, bidders had to offer fixed revenue per passenger to the authority.

A change in the revenue share model was sought after AAI felt that the operators weren’t showing enough revenue from airport operations, leading to lower payment to AAI, forcing the government to look at other methods of revenue share. It also helped that the government did away with the requirement of prior experience while bidding for projects.

Across the six airports that had recently invited bids from the private sector, passenger traffic was to the tune of 30 million passengers—23.6 million domestic and 6.4 million international—last fiscal, according to research agency ICRA. In contrast, the GMR group-run New Delhi airport handled 65.69 million passengers in fiscal 2018 while the GVK group-run Mumbai airport saw 48.5 million travellers during the same period.

“The Adanis are buying into profitable airports that see a large number of passengers and have the potential to grow in the future,” says Mark Martin, founder of Dubai-based aviation consultancy firm Martin Consulting. “Unlike before, flying isn’t a luxury anymore. It is a necessity and that means we are seeing huge growth in passenger traffic.”

For airport operators, much of their revenue comes from the non-aero side that includes retail and monetising real estate across airports. Passenger traffic across India is set to swell and the International Air Transport Association reckons that the number of airline passengers in the country is set to touch 50 crore by 2037 even as airline companies struggle to keep up with growing demand for pilots and fluctuating oil prices.

Despite all this, Adani’s entry into the aviation sector is likely to bring more stability and growth. “Having a new player in the market breaks cartels and creates a level-playing field, so a lot depends on how focussed they are with airport development,” adds Martin.

(This story appears in the 29 March, 2019 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X