The surge in the deadly Covid-19 virus worldwide last year followed by the sudden complete lockdown imposed in India from March 24, 2020, left many poignant images of the plight of the country’s poor and migrants. One such image was of a dead woman lying on the Muzaffarnagar platform while a toddler, presumably hers, was tugging at the sheet on which she was lying.

The woman was Arvina Khatoon, a migrant from Srikol village in the Katihar district of Bihar. It is said that she died of dehydration and hunger, while returning to her native village after she lost her job during the pandemic, and all sources of income and food.

Initially, it was said the coronavirus does not differentiate between the rich and the poor, and men and women. However, with the passage of time, it was evident that the existing socioeconomic inequalities have led to an unequal health and economic impact among the various population sub-groups and defined their coping abilities in recovering from the crisis. The increasing inequality and the unequal impact on the haves and have-nots have prompted many to refer to the health crisis as the “pandemic of inequality". Antonio Guterres, the United Nations Secretary General, rightly put it in his speech at the Nelson Mandela Foundation in 2020 when he said, “The Covid-19 pandemic has played an important role in highlighting growing inequalities. It exposed the myth that everyone is in the same boat. While we are all floating on the same sea, it’s clear that some are in superyachts, while others are clinging to the drifting debris."

The heart-wrenching image of Khatoon tells a grim picture of the huge price that women, both poor and from the middle-class, paid as a consequence of the economic shock that was brought on by the pandemic and the ensuing lockdowns in India. Women are likely to face the brunt of job losses the most because of the precarity of their jobs, lack of job security, invisibalisation of their work, and for working mostly in informal arrangements. Seventeen million women lost their jobs in April 2020. Unemployment for women rose by 15 percent from a pre-lockdown level of 18 percent. This increase in unemployment of women can result in a loss to of about 8 percent or $218 billion to the GDP. Women who were employed before the lockdown are also 23.5 percentage points less likely to be re-employed compared to men in the post-lockdown phase.

![]() The pandemic saw a rise in women’s unpaid care work burden, reversing decades of hard work put in by feminists to recognise it

The pandemic saw a rise in women’s unpaid care work burden, reversing decades of hard work put in by feminists to recognise it

Image: Burhaan Kinu / Hindustan Times via Getty Images

Eight months after the lockdown last year, 13 percent fewer women were employed or looking for jobs, compared to 2 percent men. Urban women more so than rural women. After the massive dip in employment in April 2020, job recovery has steadily risen, but been tilted in favour of men than women. According to IndiaSpend, using Centre For Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) data, total employment in India for November 2020 was 2.4 percent lower than in November 2019, but for urban women, it was down by 22.83 percent. In November 2020, eight months since the lockdown was imposed, there were 6.7 million fewer women in the labour force compared to November 2019. In other words, 13 percent women were neither looking for a job nor were they employed. Labour force contraction was 27.2 percent for women as compared to 2.8 percent for men.

According to Mahesh Vyas of CMIE, women act as reserve labour force in the Indian economy. During economic shocks, they withdraw. The downside is that their recovery—when the shock recedes and things come back to normal—is not always similar to its pre-shock phase. For example, in the aftermath of demonetisation, 2.4 million women fell off the employment picture in India whereas 0.9 million men joined the jobs market, says Vyas. A similar replacement pattern of men replacing women in the labour force is being witnessed in the aftermath of the pandemic and lockdowns. In November 2020, 20 million or 67 percent of 30 million unemployed men were actively looking for jobs whereas only 7.2 million of the 19.6 million unemployed women or 37 percent were actively looking for jobs, according to CMIE data.

Why women drop off the labour force and don’t come back is a complex web of reasons—precarity and informality of their work conditions lack of social security and health standards wage inequality social and cultural barriers to women’s employment unpaid care work responsibilities and expectations from women lack of safe and affordable public transportation lack of child care options and inadequate government policy interventions to improve working conditions of women are some of the major reasons.

Middle-class women were faring no better than their poorer sisters during the lockdown. Specifically, the pandemic and lockdowns saw a phenomenal rise in women’s unpaid care work burden, reversing decades of hard work put in by feminists to recognise and reduce the same. While most managed to keep their jobs, they ended working much harder than normal times. With schools, day care centres and creches closed, child care, looking after and supervising children’s online classes were new responsibilities that the women had to take up. In addition, those with part-time domestic help were left to take care of the house and cooking all by themselves as these domestic workers could not report to work. Elder care was also added to the pool. In fact, the Odisha government issued a public interest advisory exhorting men not to take the lockdown as a holiday and instead become responsible and help with domestic chores at home.

A survey by the Institute of Social Studies Trust (2020) found that among those who could retain their jobs, around 83 percent of women workers faced a severe drop in income. Sixty-six percent of the respondents also experienced an increase in unpaid care work and 36 percent reported an increased burden of child and elderly care work during this period. According to the latest NSSO Time Use Survey 2019, before the pandemic, rural and urban women spent 373 minutes and 333 minutes per day respectively in paid and unpaid activities combined. The total time has now risen with the increase in the workload as a result of being stuck at homes. A study by researcher Priyanshi Chauhan found that approximately 22.5 percent married women compared to zero men and unmarried women worked for more than 70 hours a week during the lockdown. The study also observed that unemployed women witnessed the highest increase of 30.5 percentage points for those who spent more than 70 hours per week on unpaid work.

The work-from-home culture has also blurred the lines between working hours and personal downtime. Women have been working longer hours and simultaneously managing the daily household chores, educational needs of children and care for all family members.

Frontline health workers such as ASHAs (Accredited Social Health Activists) whose work can be seen as an extension of care work have experienced a phenomenal increase in their work. But the remuneration is way too measly—a mere ₹1,000 for Covid-19 duties assigned to them. In most cases, they were sent out on Covid-19 duty with no or inadequate protective gear, thereby exposing them to the virus while they worked for the betterment of their countrymen and women. Oxfam estimates that if India’s top 11 billionaires are taxed at just 1 percent on their wealth, the government can pay the average wage of the 9 lakh ASHA workers for five years.

A third area where women suffered the most was domestic abuse—physical, mental and emotional. Indeed, the phenomenal spike in domestic abuse during the pandemic led the United Nations to declare it as a ‘shadow pandemic’. By the second month of the lockdown, complaints about domestic abuse doubled in India. Such complaints rose from 116 in the first week of March to 257 in the final week of March 2020. According to the National Commission for Women (NCW), it registered an increase of 2.5 times in complaints of domestic violence in April 2020 from the previous year. The NCW received 5,297 complaints in 2020 compared to 2,960 in 2019, a 79 percent increase in cases.

Cases have been increasing since April. The highest number was in July (660), but it has stayed above 450 a month since June. Total cases in April, May and June combined—the initial months of the lockdown was 1,169. In 2020, between March 25 and May 31, 1,477 complaints of domestic violence were made by women. This 68-day period recorded more complaints than those received between March and May in the previous 10 years.

It is also common knowledge that cases of domestic violence are grossly under-reported. Thus, despite the huge spike in cases registered, it is understood that hundreds and thousands went unreported.

The reason for such a rise in cases was that due to the lockdown, women got trapped at home with their abusers—husbands, in-laws and others. With no scope to leave home, it was a fatal situation for many. It is said that alcohol abuse is a common form of domestic abuse. During the lockdown, alcohol sale was banned. But this led to a reverse form of abuse—men were beating up their women out of frustration for forced abstinence. Besides, loss of jobs and income, the inability to step out of their home and general frustration led to higher incidences of violence against women and girls.

The lockdown and lock-in of women with their abusers meant that abusers had access to the phones and other means of communication that the women use to reach out for help. Thus, while helpline numbers did see a spike in distress calls, they failed to connect with many more women who couldn’t escape the surveillance of their abusers. In this regard, the government of Jammu & Kashmir created a unique system where they provided access to helpline numbers for women in pharmacies and grocery stores. These were open during the lockdown and presumably women frequented them for their families’ needs. These were least likely expected to be safe zones for women and they could escape the surveillance of their abusers. Many such initiatives were necessary to support women during the lockdown. It was not until a few weeks into the lockdown that the government declared that shelter homes for women domestic violence survivors were part of essential services. Even then, the issue of leaving their homes and reaching a shelter home remained a concern.

If violence against women and girls was an existing curse, the situation exacerbated multiple times during the pandemic. Indeed, a deadly combination of job and income loss, reduced bargaining power with the family, high burdens of unpaid care work, the inability to step out of home for relief and to seek help created a volatile situation and made the lives of many more women precarious. In future, the government should be especially mindful of the fact that women are disadvantaged in the Indian society and need to be extended every form of support to ensure that their condition does not deteriorate further.

It is necessary to build economically resilient communities especially targeting vulnerable groups such as poor women and girls. The government should revise minimum wages and enhance them at regular intervals on the basis of Consumer Price Index. Monitoring mechanisms should also be endorsed to ensure that informal workers such as domestic workers receive minimum wages. Also, informal workers should be formalised through written contracts and provided access to social security benefits such as medical, paid and maternity leave, and Provident Fund. Several steps such as creating an MIS for migrant workers (inflow and outflow) by district labour officers and standard operating procedures for employers (those who are employing migrant labourers) to make provisions of minimum facilities at the workplace and on their behaviours towards the workers during pandemic should also be initiated.

â— The writer is an international consultant working on Social Development Research

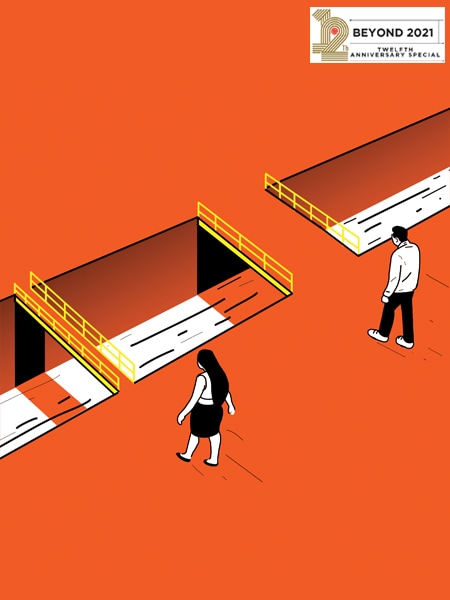

Illustration: Sameer Pawar

Illustration: Sameer Pawar Covid-19 has shown that women are more likely to face the brunt of job losses than men, and find fewer opportunities when they want to resume. That apart, several have to deal with increased hours of unpaid work at home and even domestic abuse

Covid-19 has shown that women are more likely to face the brunt of job losses than men, and find fewer opportunities when they want to resume. That apart, several have to deal with increased hours of unpaid work at home and even domestic abuse The pandemic saw a rise in women’s unpaid care work burden, reversing decades of hard work put in by feminists to recognise it

The pandemic saw a rise in women’s unpaid care work burden, reversing decades of hard work put in by feminists to recognise it